You've probably seen them dangling from the rafters of an old barn or rigged up on a sailboat, looking like a confusing mess of rope and wooden blocks. Honestly, the block and tackle pulley is one of those inventions that feels like cheating. It’s a basic machine, sure, but it’s the reason a single person can lift a literal ton without blowing out their back or needing a massive hydraulic crane.

It's physics. Pure and simple.

When we talk about lifting heavy stuff, most people think about raw strength. But the block and tackle is about trading distance for force. You pull a lot of rope, and the weight moves just a little bit. It's a trade-off. If you want to lift 400 pounds but your muscles can only handle 100, you need a 4:1 mechanical advantage. You’ll pull four feet of rope for every one foot the load rises.

📖 Related: Andromeda Galaxy: What Most People Get Wrong About Our Closest Neighbor

People get this wrong all the time. They think the pulley "creates" energy. It doesn’t. You're still doing the same amount of work (Force × Distance), you’re just spreading that work out over a longer period. It's the difference between sprinting up a vertical cliff and walking up a long, gentle ramp. Both get you to the top, but one is actually possible for a human being.

How the Hardware Actually Works

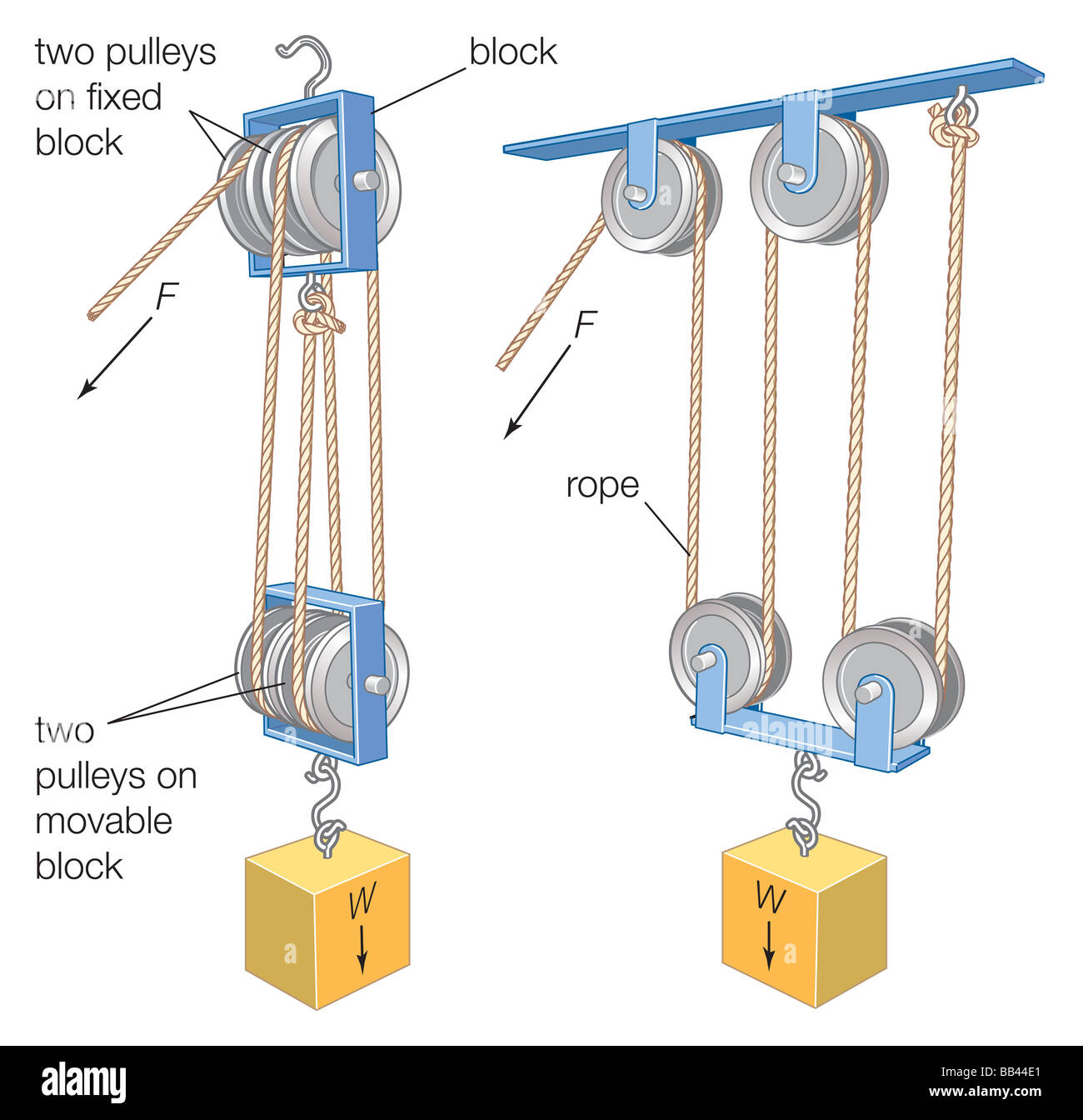

A "block" is just the casing that holds the sheaves—those are the little wheels inside that the rope actually sits on. The "tackle" is the rope itself. When you thread that rope through multiple sheaves between a fixed point and a moving load, you’re creating multiple "parts" of the line that support the weight.

Here is the secret: The mechanical advantage (MA) is basically equal to the number of rope segments supporting the moving block.

If you have a double block at the top and a single block at the bottom, and the rope is tied to the bottom block, you’ve got three lines pulling up. That’s a 3:1 ratio. Simple? Sorta. But friction is the enemy. Every time that rope bends around a sheave, you lose energy. In a cheap setup with plastic wheels and rough rope, you might lose 10% of your effort to friction at every single turn. By the time you get to a 6:1 system, you're fighting the machine almost as much as the gravity.

The Friction Tax

Archimedes is usually the guy credited with really figuring this out. Legend says he used a complex system of pulleys to single-handedly pull a fully-loaded galley ship out of the water and onto the beach. While that might be a bit of ancient PR fluff, the math holds up.

Modern maritime experts like those at Harken or Lewmar spend millions of dollars just trying to kill friction. They use ball bearings and high-tech composites because, in a high-load situation like a racing yacht, a stuck sheave can snap a line and send a mast crashing down. For a backyard DIYer, though, a bit of grease and a decent braided nylon rope usually do the trick.

Real-World Rigging: More Than Just Lifting

It’s not just for construction sites.

Think about vehicle recovery. If you’re off-roading and your truck gets buried in axle-deep mud, a winch is great. But sometimes a winch isn't enough. By using a snatch block—a specific type of block and tackle pulley component—you can double the pulling power of your winch. You run the cable out to a tree, through the block, and back to your own bumper. Now you’ve got a 2:1 advantage. Your 8,000-pound winch is suddenly behaving like a 16,000-pound beast.

Arborists use these systems daily. When they need to lower a massive oak limb over a glass sunroom, they don't just drop it. They use a "friction hitch" or a block-and-tackle setup to control the descent. It’s about precision.

Why Choice of Rope Matters

Don’t use hardware store clothesline. Just don't.

👉 See also: Best VR Headsets for Porn: What Most People Get Wrong

Rope stretch is a massive energy suck. If you’re using a stretchy polyester rope in a 4:1 system, the first few feet of your pull are just taking the "boing" out of the line. For a block and tackle to be efficient, you want "static" line—rope that doesn't stretch. Professional riggers often use AmSteel or other Dyneema-based ropes because they’re stronger than steel cable but as light as a feather.

The Math You Actually Need

Let’s be real: nobody wants to do calculus while they’re trying to lift an engine block.

$$MA = \frac{F_{out}}{F_{in}}$$

Basically, your Mechanical Advantage ($MA$) is the Output Force divided by your Input Force. If the engine weighs 600 lbs and you pull with 150 lbs of force, you have a 4:1 advantage.

But remember the "Rule of Thumb" for friction: Add about 10% to the weight for every sheave in the system. If you have four sheaves, treat that 600 lb engine like it weighs 840 lbs when you're calculating how much strength you need. It’s better to over-engineer than to have a rope snap in your face.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

The biggest mistake is "two-blocking." This happens when the two blocks (the top one and the bottom one) get pulled so close together that they touch. Once they hit, you can’t lift any higher. It sounds obvious, but when you're focusing on the load, it's easy to forget to watch the blocks.

Another one? Using the wrong sized rope for the sheave. If the rope is too fat, it rubs against the sides of the block (the cheeks). This creates massive heat and friction. If the rope is too thin, it can get wedged between the sheave and the casing, which usually ends with a shredded rope and a dropped load.

Buying vs. Building

You can buy a pre-made "power puller" for fifty bucks online. They're okay for light work. But for anything serious, you want to buy the blocks and rope separately. Look for:

- Swivel heads: Prevents the rope from twisting into a tangled mess.

- Beckets: This is the little loop at the bottom of a block where you tie off the end of the rope.

- Working Load Limit (WLL): Never, ever exceed this. And remember, the WLL of the system is only as strong as its weakest link. If you have 5,000 lb blocks but a 1,000 lb rope, you have a 1,000 lb system.

Practical Next Steps for Your Project

If you're looking to set up your own block and tackle pulley system for a garage or a project, don't just wing it. Start by weighing your heaviest expected load.

- Calculate your needed ratio. If you want to lift it with one hand, aim for at least 4:1 or 5:1.

- Inspect your anchor point. A pulley is only as good as the beam it's hanging from. A 4:1 system doesn't reduce the weight on the ceiling; in fact, because of the extra rope and your own pulling force, the ceiling actually feels more weight than just the load itself.

- Buy quality blocks. Brands like Harken (for marine) or Crosby (for industrial) are the gold standard.

- Practice a "dead lift" first. Test the system with something non-breakable just a few inches off the ground to check for rope slip or block misalignment.

Understand the physics, respect the friction, and you can move almost anything. Just keep your fingers out of the sheaves.