You've probably seen a block and tackle pulley system without even realizing it. It’s that clump of ropes and wheels dangling from a sailing mast or a construction crane. It looks like a tangled mess. Honestly, it’s one of the most elegant examples of mechanical advantage ever dreamed up by humans. We’re talking about a technology that helped build the pyramids and still keeps modern cargo ships running today.

Physics is a weird thing. You can’t get something for nothing, right? But with a block and tackle, it feels like you’re cheating. You pull a long length of rope with a little bit of force, and on the other end, a massive weight lifts off the ground like it’s made of feathers. It's not magic; it’s just the clever redistribution of work over distance.

The Basic Anatomy of the Block and Tackle

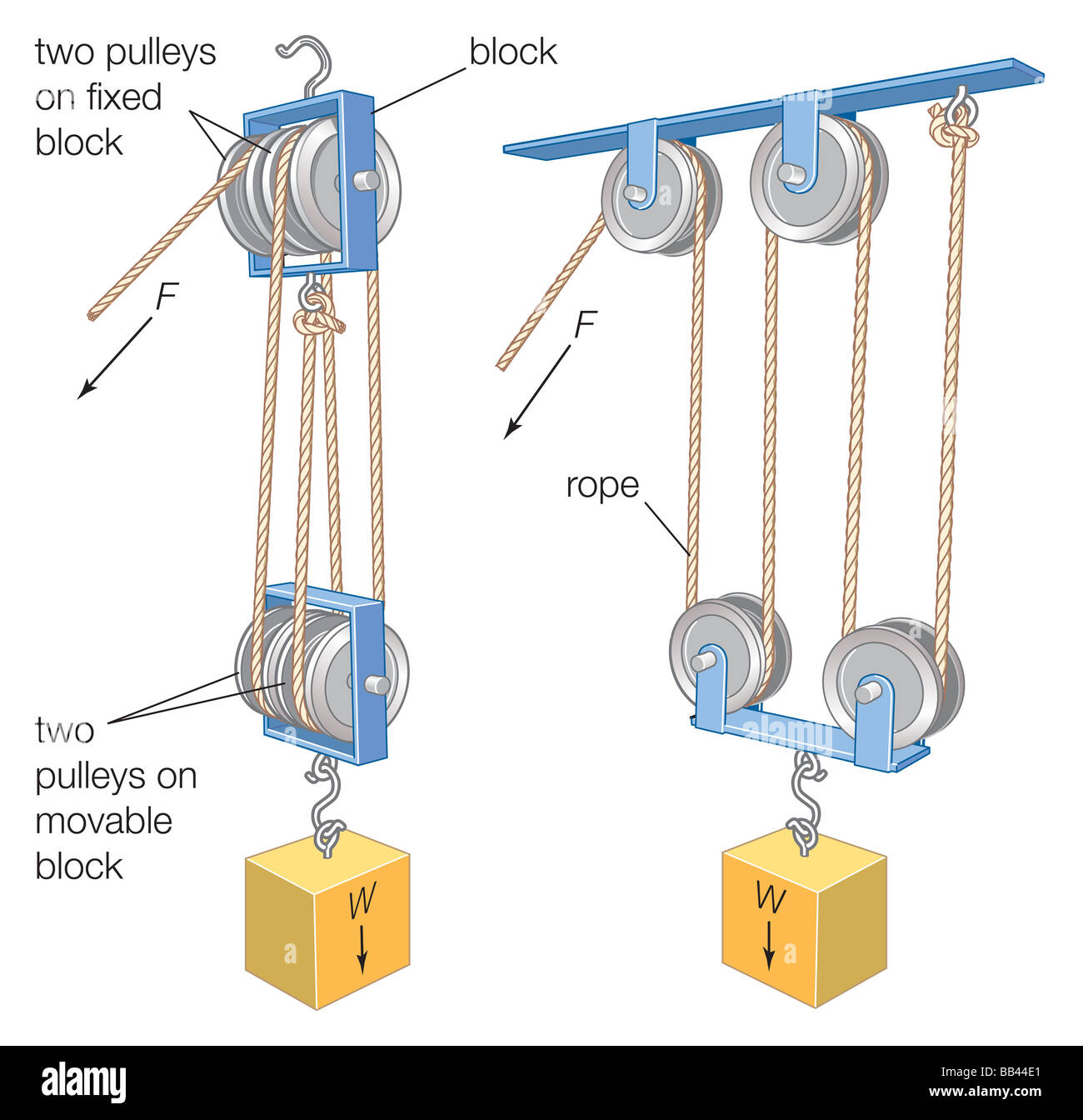

People often get confused by the terminology here. A "block" is basically just the housing—the frame that holds the wheels. Those wheels? They’re called sheaves. When you combine two or more of these blocks with a rope (the "line") threaded between them, you officially have a block and tackle pulley system.

It’s an old-school setup.

The "standing block" is the one that stays put, usually fixed to a beam or a hook. The "running block" is the one that moves with the load. The more times the rope loops back and forth between these two blocks, the more mechanical advantage you get. This is the core of how it works. If you have four ropes supporting the load, you only have to pull with one-fourth of the weight's force. But there's a catch. You have to pull four times as much rope.

👉 See also: Cheapest Ring Video Doorbell Explained (Simply)

Why Friction Is Your Biggest Enemy

In a perfect textbook world, adding more sheaves makes life easier forever. In the real world, physics eventually bites back. Every time that rope passes over a sheave, you lose energy to friction. If you’re using cheap plastic pulleys or a rough hemp rope, the friction can get so bad that adding another wheel actually makes the job harder.

This is why professional rigging uses ball bearings and high-tensile synthetic lines. Archmedes, the guy who supposedly used a pulley system to pull a fully laden ship onto the beach by himself, didn't have Dyneema rope. He had to deal with massive amounts of internal resistance. When you're designing a system today, you've gotta account for about a 10% loss in efficiency for every single sheave in the block.

Mechanical Advantage: The Math You’ll Actually Use

Let's get into the nitty-gritty of the "Mechanical Advantage" or MA. It’s a simple ratio. If you have a 100-pound crate and you only need to pull with 25 pounds of force to lift it, your MA is 4.

How do you find the MA just by looking at a block and tackle pulley system? Simple. Count the number of rope segments supporting the moving block. Don't count the part of the rope you’re actually holding in your hand unless you’re pulling upwards to lift the load. If you're pulling down, that last bit of rope is just changing the direction of the force, not adding to the lifting power.

The "Gun Tackle" vs. The "Luff Tackle"

Sailing history gives us some cool names for these setups. A "Gun Tackle" uses two single-sheave blocks. It’s the simplest version, giving you a 2:1 or 3:1 advantage depending on which way you rig it.

The "Luff Tackle" is where things get serious. This uses a double block and a single block. You’ll see these used on sailboats to tension the sails or on small farms to pull engines out of trucks. Then you have the "Twofold Purchase," which uses two double blocks. By the time you get to a "Threefold Purchase" (two triple blocks), you’re looking at a 6:1 advantage. At that point, a single person can move over half a ton.

Real-World Applications That Aren't Just History

Think this is just for museums? No way.

- Arborists: Tree climbers use these daily. When a massive oak limb needs to be lowered slowly without crushing a homeowner's roof, a block and tackle (often called a "fiddle block" in this industry) provides the control needed.

- Theater Technicians: How do you think those massive sets move silently during a play? Stage rigging is almost entirely based on these principles.

- Off-Roading: If your Jeep gets stuck in a mud hole and your winch isn't strong enough, you use a "snatch block." That’s just a block and tackle in disguise. By looping the winch cable through a block attached to a tree and back to your bumper, you’ve doubled your pulling power instantly.

The system is also vital in "Lifeboat Davits." When a ship is sinking, those heavy boats need to be lowered into the water with zero room for engine failure. Gravity and a solid block and tackle pulley system are more reliable than any motor in a crisis.

Common Mistakes People Make When Rigging

Most people fail at the "reeving" stage. Reeving is just the fancy word for threading the rope through the pulleys. If the ropes cross or rub against each other, they’ll fray and snap. It's dangerous.

Another huge mistake is ignoring the "SWL" or Safe Working Load. Every block has a limit. Just because you can lift a car with a 4:1 system doesn't mean the hooks on the blocks won't straighten out and drop the whole thing on your toes. Always check the stamp on the side of the block.

And for heaven's sake, don't use a block and tackle to lift people unless the gear is specifically "man-rated." There's a massive difference between a pulley designed for a hay bale and one designed for a human life.

Material Matters More Than You Think

Steel blocks are the gold standard for construction, but they’re heavy. If you’re backpacking or sailing, you want aluminum or composite. The rope matters too. Natural fiber ropes like manila are classic, but they rot if they get wet. Modern polyester or nylon ropes stretch. Stretch is actually bad for a block and tackle because you spend the first ten feet of your pull just tightening the rope instead of lifting the load. For a serious block and tackle pulley system, you want "low-stretch" or "static" line.

Setting Up Your Own System: A Quick Guide

If you're looking to put one of these together in your garage, don't overcomplicate it.

First, figure out your weight. If you're lifting a 200lb engine, a 4:1 system (two double blocks) means you're only pulling 50lbs. That's manageable for most people.

Second, buy "swivel" blocks. Trust me. If the blocks can't spin to find their own natural alignment, the rope will jump the track (the "sheave") and jam. It's a nightmare to fix when there's a load in the air.

Third, check your anchors. A block and tackle pulley system is only as strong as what it’s hanging from. If you hook a 5:1 system to a flimsy garage rafter, you might pull the roof down before the load ever leaves the ground.

The Future of the Block and Tackle

We're seeing a move toward "soft shackles" and friction rings in the high-end racing world. Some people argue that these rings—which have no moving parts—will replace the block and tackle. But there's a catch. Friction rings require incredibly expensive, slippery ropes to work. For the average person, the classic wheel-in-a-frame isn't going anywhere.

It’s one of the few technologies that reached "peak design" hundreds of years ago. We’ve changed the materials from wood and hemp to carbon fiber and Technora, but the physics remains identical to what the Romans used.

Actionable Steps for Using a Block and Tackle

To get the most out of a pulley setup, start by calculating your required mechanical advantage based on the heaviest load you expect to lift. Always buy blocks with a Safe Working Load that is at least double your intended weight to account for dynamic forces—like the load bouncing.

👉 See also: DALL E Image Generation: What Most People Get Wrong

Before every lift, perform a "dry pull" without the weight to ensure the lines aren't twisted. If you notice any fraying on the rope or "slop" in the pulley wheels, replace them immediately. For long-term installations, lubricate the sheaves with a dry Teflon spray rather than grease, as grease tends to attract grit that will eventually grind down the bearings. Finally, always stand clear of the "snap zone"—the path the rope would take if the anchor point failed. Safety in rigging is about respecting the immense tension stored within the system.