Steve Winwood was barely twenty-one when he sat down at a piano and conjured one of the most haunting melodies in the history of British rock. It’s a song about spiritual exhaustion. It’s a song about being utterly lost. When you listen to blind faith can't find my way home, you aren't just hearing a folk-rock ballad; you’re hearing the sound of a "supergroup" imploding before it even really started.

Music history is littered with ego-driven disasters.

But this was different.

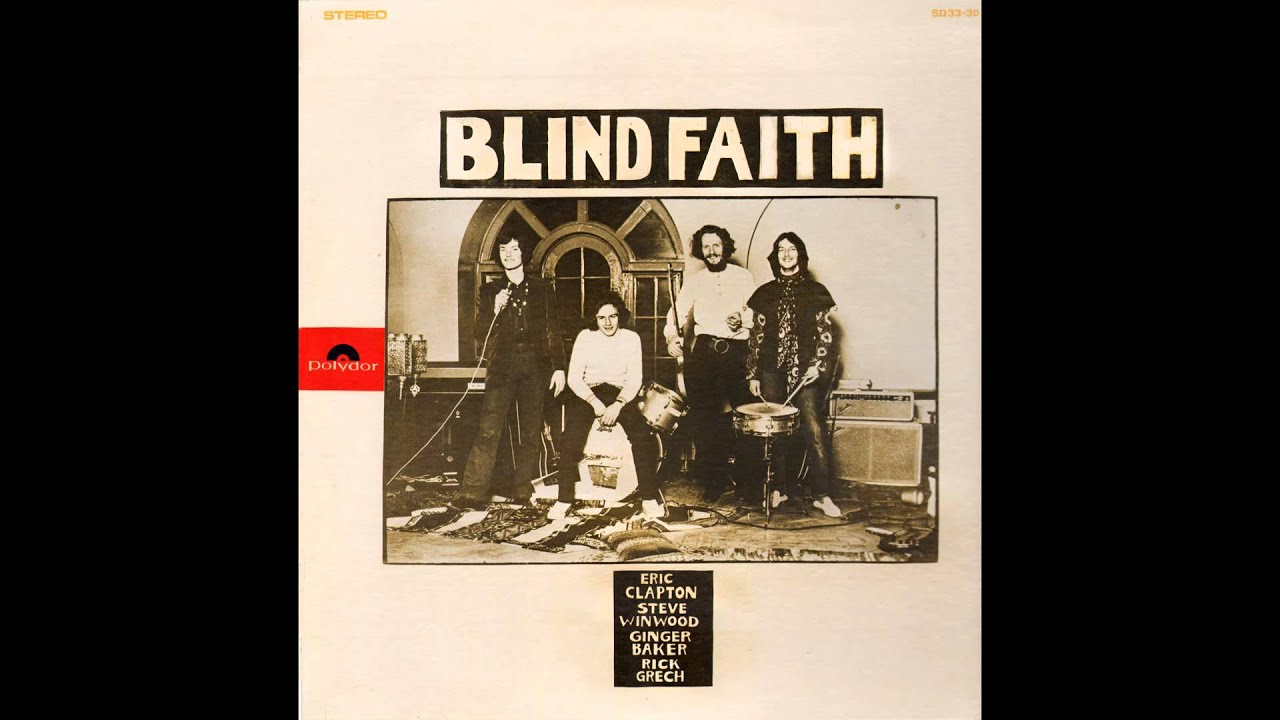

In 1969, the world was obsessed with the idea of Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood joining forces. After the high-volume theatrics of Cream and the psychedelic soul of Traffic, the expectations were, frankly, impossible to meet. They moved into a house in the English countryside to escape the "star" system, trying to find a sound that felt honest. What they found instead was a deep, nagging sense of displacement.

Why the Lyrics Still Hit Different

Most people think the song is a simple religious plea. It isn’t. Or at least, it’s not just that. When Winwood sings about being near the end and losing his direction, he’s talking about the burnout of being a child prodigy in a predatory industry. He’d been famous since he was fifteen. By the time Blind Faith formed, he was tired.

"I'm wasted and I can't find my way home."

It’s a blunt line. It’s not poetic in a flowery way. It’s a confession. Honestly, the beauty of the track lies in its acoustic simplicity, which was a massive pivot from the "God" persona Clapton had been saddled with during his time in Cream. Ginger Baker’s percussion on the track doesn’t drive the song forward so much as it floats alongside it. It’s ethereal.

🔗 Read more: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

The Ginger Baker Factor

People forget how volatile this lineup was. You had Rick Grech on bass, Winwood’s soulful vulnerability, and then you had Ginger Baker. Baker was a force of nature—often a terrifying one.

His drumming on this specific track is a masterclass in restraint. He uses brushes. He plays with a light touch that feels like a heartbeat skipping. If he had played it like a standard rock drummer, the song would have lost its fragility. It’s that fragility that makes the listener feel the "lost" sentiment so deeply.

The Hyde Park Debut and the Death of the Dream

On June 7, 1969, Blind Faith played to a massive crowd in London’s Hyde Park. Over 100,000 people showed up. They wanted "Sunshine of Your Love." They wanted pyrotechnics.

Instead, they got a band that was still figuring out its identity.

The performance of blind faith can't find my way home was a standout, but the pressure of the event essentially broke the band’s spirit. Clapton was famously shy during the gig. He spent much of the time hiding behind his amplifiers. He didn't want to be a guitar hero anymore; he wanted to be a musician in a collective. The irony is that the more they tried to find "home" through their music, the more the industry pushed them into the spotlight.

Recording the Self-Titled Album

The recording process at Olympic Studios was rushed. Jimmy Miller, the legendary producer who worked with the Rolling Stones, was at the helm. He knew how to capture grit.

💡 You might also like: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

The song relies on an open-tuned acoustic guitar, creating a drone-like quality that feels ancient. It borrows from the English folk tradition as much as it does from American blues. This hybridity is why the song hasn't aged a day since 1969. It doesn't belong to a specific era.

Misconceptions About the Song's Meaning

You'll hear people argue that it's a drug song.

"Wasted" usually implies intoxication in a modern context. But in 1969, Winwood was using the word in its more literal, exhausted sense. He was spent. The "home" he was looking for wasn't a physical house; it was a state of being where he wasn't being commodified by record labels and screaming fans.

- Myth: The song was written about Eric Clapton's struggles.

- Fact: Steve Winwood wrote the music and lyrics entirely on his own.

- Myth: It was a massive chart-topping single.

- Fact: It was actually the B-side to "Presence of the Lord" in some territories, though it eventually became the band's most enduring legacy.

The Cultural Shadow of Blind Faith

The band lasted less than a year. One album. One tour. That was it.

The album cover—featuring a topless young girl holding a silver hood ornament—caused more of a stir than the music at first. It was a PR nightmare. But the music on the record, specifically the closing track, outlived the controversy.

Cover versions have popped up everywhere from Joe Cocker to Alison Krauss. Each artist tries to capture that specific loneliness Winwood voiced. But there’s something about the original's high-tenor vocal that feels irreplaceable. It’s the sound of a man realizing that the "supergroup" experiment was a gilded cage.

📖 Related: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

How to Listen to it Today

If you’re coming to this track for the first time, skip the remastered "loudness war" versions if you can. Find an original vinyl pressing or a high-fidelity digital master that preserves the dynamic range.

You need to hear the space between the notes.

The song is built on silence as much as it is on sound. When the bass drops out and you’re left with just the acoustic guitar and Winwood’s voice reaching for those high notes, that’s where the magic happens.

Modern Interpretations

In the 2020s, the song has taken on a new life in the "desert rock" and "indie folk" scenes. Musicians are rediscovering that you don't need a wall of Marshalls to sound heavy. The emotional weight of blind faith can't find my way home is heavier than any heavy metal riff because it deals with the universal fear of losing one's internal compass.

Actionable Takeaways for the Music Obsessed

To truly appreciate the depth of this track and the era that birthed it, look beyond the surface level of "classic rock" radio.

- Listen to the Hyde Park 1969 Live Recording: It’s rougher, more nervous, and arguably more honest than the studio version. You can hear the band trying to find their footing in real-time.

- Explore Steve Winwood’s Solo Work: If the "lost" feeling of this song resonates with you, his album Back in the High Life provides a fascinating bookend to the exhaustion he felt in 1969.

- Study the Tuning: For the guitar players out there, the song uses a dropped tuning that provides that rich, resonant bottom end. Learning to play it reveals how much of the melody is built into the resonance of the instrument itself.

- Read "Motherless Sons": This biography of Eric Clapton gives a gritty, unvarnished look at the mental state of the band members during the Blind Faith era, explaining why they felt so disconnected from their own success.

The story of Blind Faith is a reminder that talent doesn't always equal longevity. Sometimes, the most beautiful things are the ones that burn out the fastest. You don't have to be a 1960s rock star to feel "wasted" or lost. You just have to be human.