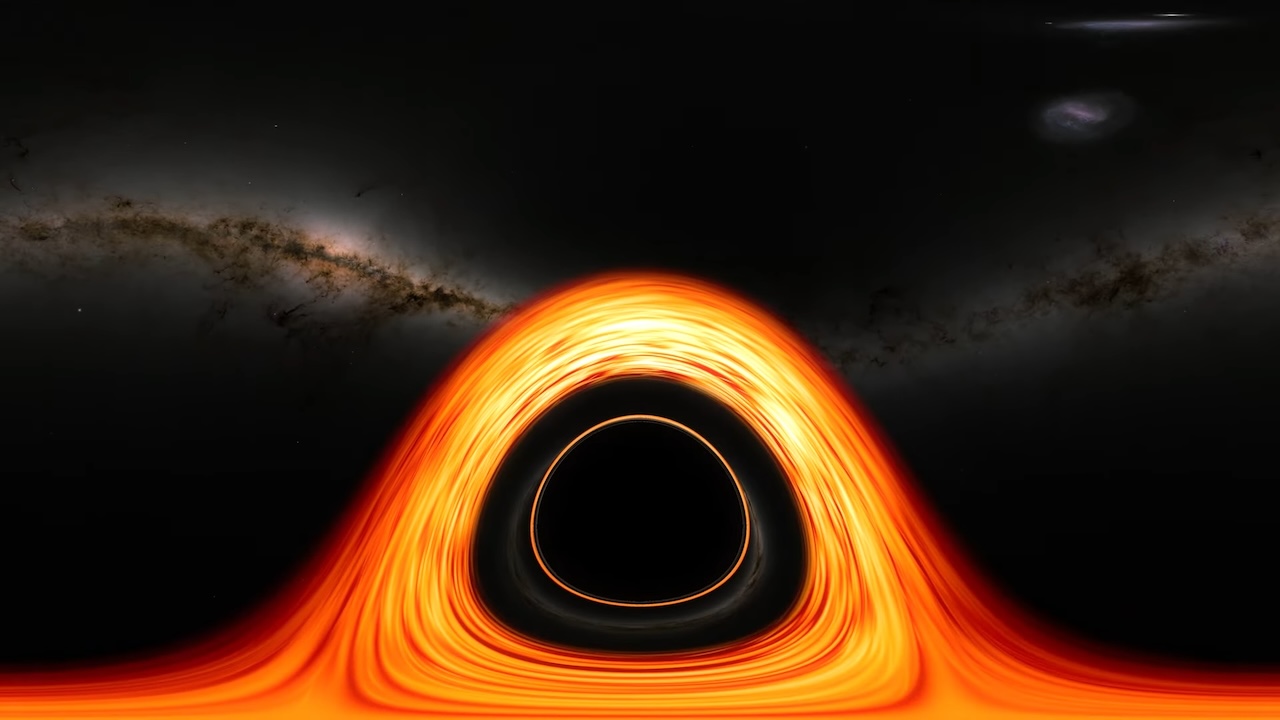

You’ve probably seen the orange donut. In 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) dropped that first blurry photo of M87*, and everyone lost their minds. But here is the thing: that image isn’t a "photograph" in the way your iPhone takes one. It is actually a massive data reconstruction, basically a high-stakes black hole simulation layered over raw radio signal captures.

Black holes are invisible. By definition, light can't escape them. So, if you want to see one, you have to simulate how gravity bends light around the "event horizon," creating a shadow. It’s a mix of hardcore Einsteinian physics and some of the most complex coding ever written. Honestly, we are at a point where our computer models are so good they can predict what a telescope will see before the telescope even turns on.

The Math Behind the Void

Space is weirdly flexible. Einstein told us that mass curves spacetime, but black holes take that to an extreme where the math starts to break. To run a black hole simulation, scientists use something called General Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamics (GRMHD). That’s a mouthful, I know. Basically, it’s a way of calculating how plasma—super-heated gas—swirls around a hole while being whipped by magnetic fields and crushed by gravity.

Dr. Avery Broderick and other researchers at the Perimeter Institute have been doing this for years. They don't just "draw" a black hole. They build a virtual universe with specific rules, drop a massive object in the middle, and see how the light from the surrounding gas gets warped.

It's called gravitational lensing. Imagine looking at a streetlamp through a wine glass base. The light gets smeared into rings. That’s exactly what’s happening in these simulations. The "shadow" in the middle isn't just the hole; it's the area where light rays are pulled inward, never to return.

Why We Need Supercomputers for This

You can't run a high-fidelity black hole simulation on a gaming laptop. Even a top-tier RTX 5090 would melt. These models require thousands of nodes on supercomputers like the Frontera system at the University of Texas. Why? Because you aren't just simulating one thing. You’re simulating trillions of particles, magnetic field lines that snap and reconnect, and the flow of time itself, which slows down as you get closer to the center.

🔗 Read more: I Need a Phone Number for Amazon Customer Service: How to Actually Reach a Human

The fluid dynamics alone are a nightmare.

Most people don't realize that the gas falling into a black hole—the accretion disk—is moving at nearly the speed of light. At those speeds, things get "beamed." The gas moving toward you looks much brighter than the gas moving away. This is why most simulations show one side of the ring being brighter than the other. If a simulation showed a perfectly even circle, the physics would actually be wrong.

The Interstellar Effect

Remember Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar? That wasn't just Hollywood magic. Kip Thorne, a Nobel-winning physicist, worked with the VFX team at Double Negative to create a proprietary renderer called DNGR (Double Negative General Relativistic Renderer).

They actually published scientific papers based on that black hole simulation.

They found that when you get close enough, the sky doesn't just distort; it wraps around you. You could theoretically see the back of your own head because light travels in circles around the "photon sphere." It’s trippy stuff. But it proves that simulations aren't just for pretty pictures; they are laboratories where we test the laws of nature.

What Most People Get Wrong

People think black holes suck things in like a vacuum cleaner. They don't. Gravity is just gravity. If our Sun were replaced by a black hole of the same mass, Earth would keep orbiting in the exact same spot. It would just be very dark and very cold.

The danger comes from the "tidal forces." In a black hole simulation, we see "spaghettification" happen in real-time. If you fall in feet-first, the gravity at your toes is so much stronger than the gravity at your head that you get stretched into a long, thin strand of atoms.

- Misconception: Black holes are giant funnels.

- Reality: They are spheres. The "funnel" look is just how we visualize the 4D gravity well on a 2D screen.

- Misconception: You see yourself die instantly.

- Reality: From your perspective, you might cross the horizon normally (if the hole is big enough). But to an outside observer, you’ll appear to freeze at the edge, turning redder and redder until you fade away.

The Future: Sgr A* and Beyond

We are now looking at our own backyard. Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*) is the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. It's smaller and much more "jittery" than M87*. Simulating Sgr A* is harder because it changes by the minute.

👉 See also: Barakah Nuclear Power Plant Location: Why It Was Built In The Middle Of Nowhere

Recent work by the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration has shifted toward "movies" rather than still images. By using black hole simulation data as a bridge, they are trying to piece together frames of the gas swirling around our central void. It’s like trying to take a photo of a spinning propeller in a dark room with a strobe light.

The goal? Testing if Einstein was actually right. So far, the simulations match the observations perfectly. It’s almost annoying. Physicists actually want the simulation to fail, because that would mean there’s "New Physics" we haven't discovered yet. But for now, General Relativity is holding up.

Actionable Steps for Exploring Simulations

If you’re fascinated by this and want to see the "invisible" for yourself, you don't need a PhD. You can actually engage with this technology right now.

1. Use Web-Based Simulators

There are open-source projects like Blacklight or the Starless renderer where you can adjust parameters like spin and tilt to see how the event horizon changes. Search for "interactive Kerr black hole simulator" to find browser-based versions that let you fly through the photon sphere.

2. Follow the EHT Data Portal

The Event Horizon Telescope project releases its raw data and the "clean-up" algorithms they use. If you have a background in Python, you can look at the eht-imaging library on GitHub. It’s the actual code used to turn radio interference into those famous donut shapes.

3. Watch the "Real" Visualizations

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center regularly releases 4K visualizations produced on their Discover supercomputer. Look for their "Dual Black Hole" simulations—seeing two of these monsters dance around each other is one of the most violent and beautiful things computer science has ever produced.

4. Explore VR Environments

If you have a VR headset, apps like Universe Sandbox or specific NASA-led VR experiences allow you to stand on the edge of a black hole simulation. It gives you a sense of scale that a flat screen simply cannot provide. You can literally see the stars behind the hole being pulled into Einstein rings as you move your head.

💡 You might also like: Apple Store Southdale Mall: Why This Edina Location Still Sets the Standard

The next decade won't just be about better photos. It’ll be about real-time video of the most extreme environments in the universe. We are building the virtual eyes to see what light itself cannot escape.