It’s black. It’s dirty. It’s basically everywhere if you look at the history of the industrial world. Honestly, when most people think of coal, they’re actually thinking of bituminous coal, even if they don't know the name. It isn't the soft, crumbly brown stuff you find in bogs, and it isn’t the shiny, rock-hard anthracite that burns like a diamond. It’s the middle child of the coal family, but it’s the one that does all the heavy lifting.

If you’ve ever flipped a light switch or looked at a steel beam in a skyscraper, you’ve probably benefited from this specific rock. Bituminous coal is a dense, sedimentary rock that formed millions of years ago. We’re talking about the Carboniferous period—roughly 300 million years back. Giant ferns and primitive trees died, sank into swamps, and got squashed by layers of dirt and water. Over time, heat and pressure cooked that organic mush into what we now call "soft coal," though it's not actually soft to the touch.

What Exactly Is the Definition of Bituminous Coal?

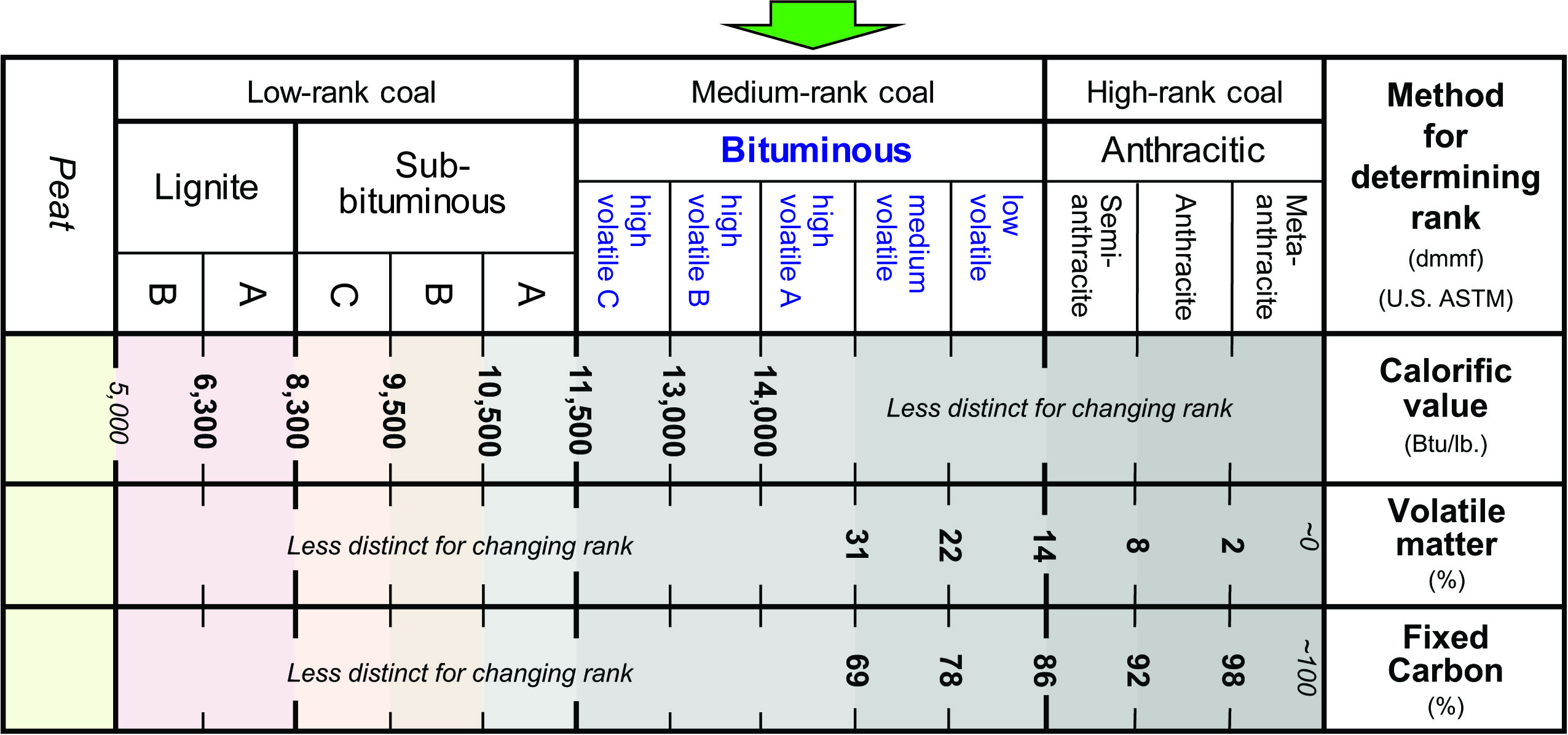

To get technical for a second, the definition of bituminous coal comes down to its carbon content and its "rank" in the coalification process. It sits right above sub-bituminous coal and right below anthracite. Usually, it contains anywhere from 45% to 86% carbon.

The name itself gives away its secret. "Bitumen" refers to a tar-like substance. When you heat this coal up, it gets soft and plastic-like because of the hydrocarbons inside. This isn't just a fun chemistry fact; it’s the reason why this specific coal is the king of the steel industry.

Why the Texture Matters

You’ll notice it has distinct layers. Geologists call these "bands." Some layers are shiny and vitreous, while others are dull and matte. This happens because the original plant matter wasn't uniform. A piece of bark preserves differently than a clump of moss. When you pick up a chunk, it might leave black soot on your hands. That’s the high volatile matter speaking.

📖 Related: Cool Designs for Cars That Actually Changed the Way We Drive

It’s a "dirty" fuel in the sense that it has a lot of sulfur and nitrogen. When it burns, it releases more than just heat; it releases smoke and chemicals that have kept environmental scientists busy for decades. Yet, its energy density is hard to beat. It packs about 24 to 35 million BTUs per ton. That’s a lot of bang for your buck, which is why utilities have clung to it for so long.

How It’s Actually Used Today

Most people assume coal is just for power plants. That's largely true for the "thermal" variety, but there’s a whole different side to bituminous coal called "coking coal" or metallurgical coal.

Electricity Generation: This is the "steam coal." It’s pulverized into a fine powder and blown into a furnace. It boils water, creates steam, spins a turbine, and boom—you have power. Even with the massive shift toward natural gas and renewables, a huge chunk of the global grid still relies on this process.

Steel Production: You can’t make modern steel without coke. To get coke, you take high-grade bituminous coal and bake it in an oven without oxygen. This drives off the impurities and leaves you with nearly pure carbon. This carbon is then used in a blast furnace to melt iron ore.

Cement Manufacturing: The high heat required to make clinker (the precursor to cement) often comes from burning bituminous coal. It provides the steady, intense temperatures that smaller fuel sources just can't match.

Chemical Feedstocks: Believe it or not, some of the dyes, perfumes, and even medicines you use have roots in coal tar, which is a byproduct of making coke from bituminous coal.

The Geography of the Black Stuff

Where do we get it? It’s not distributed evenly across the globe. In the United States, the Appalachian Basin is the historic heartland. Think West Virginia, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania. However, the Illinois Basin also holds massive reserves.

On a global scale, China is the undisputed heavyweight. They mine and burn more bituminous coal than anyone else, followed closely by India and Australia. Australia, in particular, is famous for its high-quality metallurgical coal, which they ship all over Asia to fuel the construction booms in mega-cities.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) notes that while coal production has declined in the West, the specific demand for high-volatile bituminous coal for export remains surprisingly resilient. It’s a global commodity, and the prices fluctuate based on everything from Australian floods to Chinese trade policies.

The Problem with Sulfur

One of the biggest headaches with the definition of bituminous coal is the sulfur content. There are two types: low-sulfur and high-sulfur.

High-sulfur coal is a nightmare for the atmosphere. When burned, it creates sulfur dioxide ($SO_2$), which is the main ingredient in acid rain. In the 1970s and 80s, this was a massive environmental crisis. To fix this, engineers developed "scrubbers" or Flue Gas Desulfurization (FGD) systems. These are essentially massive chemical washes that strip the sulfur out of the smoke before it leaves the chimney.

It’s expensive. It’s complicated. But without it, using bituminous coal in the 21st century would be an ecological disaster. There’s also the issue of "fly ash," the fine particles left over after combustion. This stuff contains heavy metals like arsenic and mercury. Managing coal ash ponds is one of the most litigious and difficult parts of running a modern coal-fired power plant.

Misconceptions People Have

A lot of folks think all coal is the same. It's not. If you try to use lignite (brown coal) in a steel mill, you’ll fail miserably; it doesn't have the "caking" properties. If you use anthracite in a power plant designed for bituminous, the furnace might get too hot or not ignite properly because anthracite is so hard to light.

Another myth is that "clean coal" is a specific type of rock. It’s not. Clean coal refers to the technology used to burn it—like Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS). Bituminous coal is inherently "unclean" in its raw state, but we've spent billions trying to find ways to use its energy without the heavy carbon footprint.

👉 See also: CS 2110 Computer Organization and Programming at Georgia Tech: Surviving the Gateway to Systems

Practical Steps and the Path Forward

If you are involved in energy scouting, land investment, or just curious about the grid, here is what you need to know about the current state of bituminous coal:

- Check the Rank: If you are looking at coal for industrial use, always request a "proximate analysis." This tells you the moisture, volatile matter, fixed carbon, and ash content.

- Watch the Export Market: The price of bituminous coal is increasingly tied to international demand. If China's steel production dips, the mines in West Virginia feel it almost immediately.

- Environmental Compliance: If you live near a coal-fired plant, look up their "scrubber" efficiency. Modern plants can remove over 95% of $SO_2$ emissions, but older plants may still be laggards.

- Shift Toward Metallurgical: If you're looking at the long-term viability of the industry, focus on metallurgical coal. While electricity can be generated by wind or solar, we still don't have a large-scale, cost-effective way to make "green steel" without coal-derived coke.

The era of coal might be changing, but bituminous coal isn't going to vanish overnight. Its role is shifting from a general-purpose fuel to a specialized industrial tool. Understanding its chemistry and its limitations is key to navigating the transition to a lower-carbon economy.