It’s easy to feel a bit of "virus fatigue." We've been through a lot since 2020, and every time a new headline pops up about a dairy farm in Texas or a poultry cull in Iowa, the collective eye-roll is almost audible. But here’s the thing: bird flu human transmission isn't just a scary headline meant to drive clicks. It’s a biological puzzle that scientists are watching with an intensity that borders on obsession.

H5N1 is the specific strain everyone is worried about. For decades, it was mostly a "bird problem." If you didn't work in a chicken coop, you were basically fine. Then, things shifted. We started seeing it in sea lions, cats, and—most recently and surprisingly—dairy cows. This spillover into mammals is a big deal because every time the virus jumps into a new species, it gets a fresh "training ground" to figure out how to infect us more efficiently.

The Reality of How Bird Flu Human Transmission Actually Happens

Let's be clear. You aren't going to catch H5N1 by walking past a pigeon in the park.

Transmission usually requires incredibly close, messy contact. We’re talking about people who are literally elbow-deep in the industry—farmworkers, veterinarians, or people processing raw poultry. When an infected bird flaps its wings, it kicks up dust, dander, and droplets containing the virus. If you breathe that in or it gets in your eyes, that’s your entry point.

The eyes are a weirdly specific detail in the recent US cases. In 2024, several dairy workers in states like Texas and Michigan tested positive. Their primary symptom? Conjunctivitis. Pink eye. That’s it. No catastrophic respiratory failure, just red, itchy eyes. Scientists believe this happened because of "milking aerosols." Basically, fine mists of raw milk containing high viral loads sprayed into the workers' faces.

Why the "Jump" to Humans Is Hard

The virus is currently "keyed" to avian receptors. Think of it like a lock and key. Bird cells have alpha 2,3-linked sialic acid receptors. Humans have those too, but they are tucked deep down in our lower respiratory tract—our lungs. To get sick, the virus has to bypass our upper respiratory system, where we have alpha 2,6 receptors.

This is actually a bit of a silver lining. It’s why we haven't seen sustained person-to-person spread yet. For H5N1 to become a true pandemic, it needs to mutate so that it can easily latch onto the receptors in our noses and throats. If it can do that, a simple sneeze becomes a delivery mechanism. Right now, it’s just not very good at that.

💡 You might also like: Resistance Bands Workout: Why Your Gym Memberships Are Feeling Extra Expensive Lately

What the 2024 Dairy Outbreak Taught Us

Nobody expected the cows. Seriously. For years, the script was: wild birds infect domestic poultry, poultry infect humans. Cows weren't even on the radar as a major host.

But then, the virus showed up in bovine mammary glands. The concentration of H5N1 in the raw milk of infected cows was, frankly, staggering. This changed the risk profile for bird flu human transmission because it introduced a new interface between humans and the virus.

- Raw Milk Risks: The FDA has been very vocal about this. Drinking raw, unpasteurized milk from an infected herd is a massive gamble. While pasteurization kills the virus (confirmed by multiple studies where they found viral fragments in store-bought milk but no live, infectious virus), raw milk is a direct path for the virus to enter the body.

- The "Bridge" Species: Pigs have always been the biggest concern because they have both bird-type and human-type receptors. They are "mixing vessels." Seeing the virus thrive in cows was a curveball. It suggests the virus is more flexible than we gave it credit for.

The Mortality Rate Myth vs. Reality

If you Google H5N1, you’ll see a terrifying number: 50%.

That is the historical Case Fatality Rate (CFR) reported by the World Health Organization. If 100 people get it, 50 die. But there is a huge caveat here. Most of those cases were from intense exposures in Southeast Asia and Egypt over the last twenty years, involving people who were very sick and ended up in the hospital.

Many experts, including those at the CDC, suspect the actual mortality rate might be lower because we probably miss all the mild cases. If a farmworker gets a scratchy throat or pink eye and never goes to the doctor, they aren't counted in the 50%. This doesn't mean the virus isn't dangerous—it’s extremely dangerous—but the "coin flip" survival odds might be skewed by a lack of testing in mild cases.

Variations in Strains

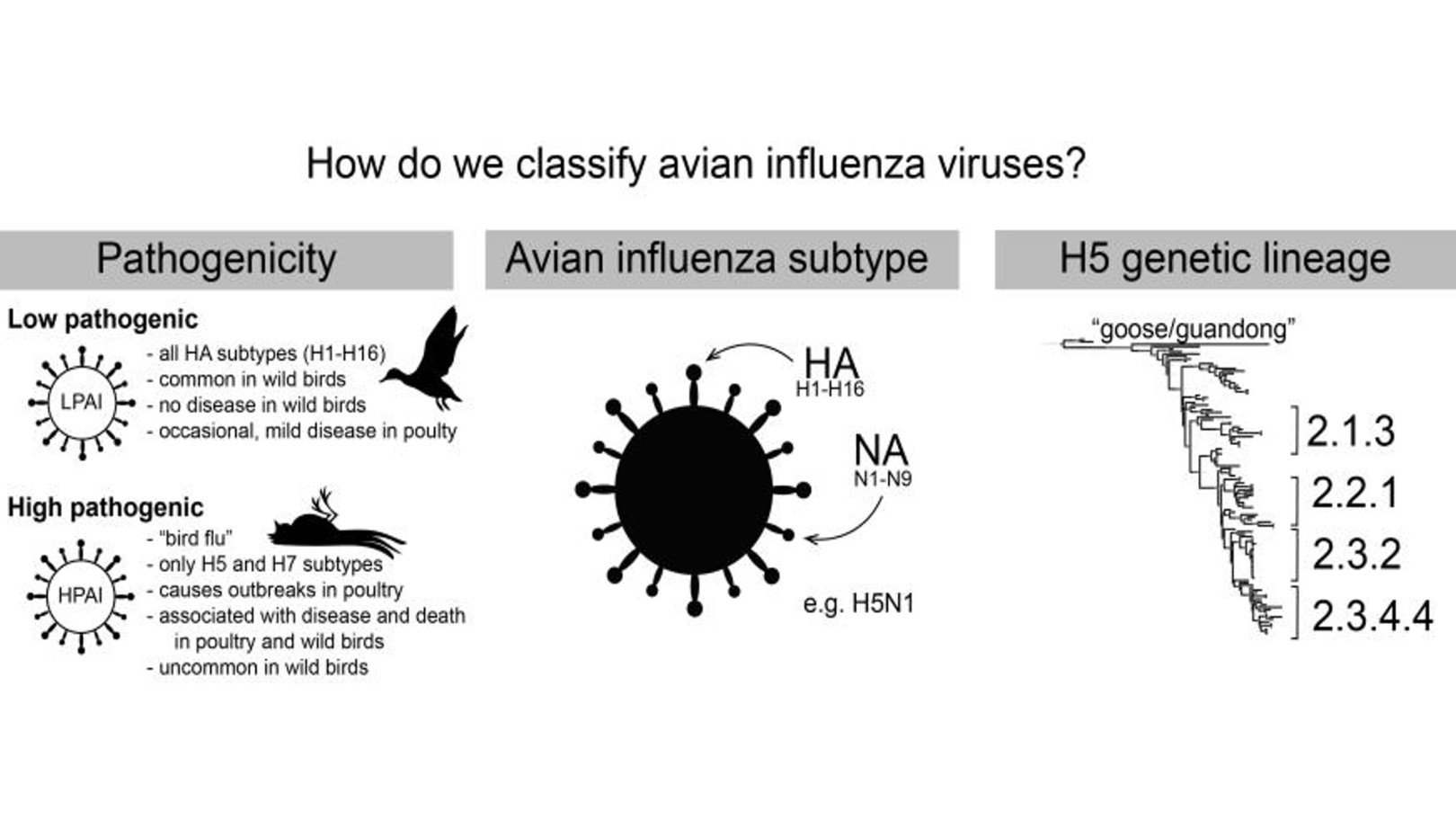

Not all H5N1 is the same. The "clade" currently circulating in North America (2.3.4.4b) seems to behave differently than the versions seen in the late 90s. While it is devastating to bird populations—killing millions of wild birds and necessitating the culling of even more poultry—the human cases in the US so far have been mild.

📖 Related: Core Fitness Adjustable Dumbbell Weight Set: Why These Specific Weights Are Still Topping the Charts

Identifying the Symptoms

If you have been around sick livestock and start feeling off, it's not just a "cold." The CDC monitors for a specific range of symptoms in suspected cases of bird flu human transmission:

- Eye Redness: As mentioned, this is the hallmark of the recent bovine-to-human jump. It looks like standard pink eye.

- Upper Respiratory Issues: Cough, sore throat, and a runny or stuffy nose.

- The Heavy Stuff: Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing. This is when the virus has made it into the lungs.

- Systemic Flags: High fever (though not everyone gets one), muscle aches, and sometimes diarrhea or nausea.

It's tricky because these look like every other winter bug. The differentiator is the exposure history. Did you touch a dead crow? Do you work on a farm? Did you visit a live bird market?

The Surveillance Gap

Honestly, the biggest hurdle to understanding the risk is the lack of testing. On many farms, there is a reluctance to test workers. There are many reasons for this: immigration status concerns, fear of losing wages, or the simple fact that if a worker feels "fine enough," they keep working.

Without robust testing of asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic workers, we are flying blind. We don't know if the virus is already starting to transmit quietly between people. Dr. Nirav Shah, the CDC's Principal Deputy Director, has repeatedly emphasized the need for better "on-the-ground" cooperation with the agricultural community.

Protective Measures That Actually Work

If you are in a high-risk environment, the standard COVID-era advice actually holds up, but with a few tweaks.

- PPE is Non-Negotiable: If you’re handling birds or livestock, N95 respirators are the gold standard. But don't forget the goggles. Since the virus likes the eyes, a mask alone isn't enough.

- Hand Hygiene: It sounds basic, but the virus is encased in a fatty "envelope." Plain old soap and water tears that envelope apart and kills the virus instantly.

- Avoid "Raw" Everything: This goes for raw milk and undercooked poultry or eggs. Heat is the enemy of H5N1. Cooking your eggs until the yolks are firm and ensuring chicken reaches an internal temperature of 165°F (74°C) makes the food perfectly safe.

Actionable Steps for the General Public

While the risk to the average person remains "low" according to the latest assessments by global health agencies, staying informed doesn't mean staying panicked.

👉 See also: Why Doing Leg Lifts on a Pull Up Bar is Harder Than You Think

Monitor Local Wildlife Reports

Check your state’s Department of Agriculture or Wildlife website. If there is a massive die-off of wild birds in your area, keep your pets away from them. Dogs and cats can catch bird flu by sniffing or biting infected carcasses.

Practice Common Sense Bird Safety

If you have backyard chickens, keep their feed and water in areas where wild birds can't get to them. If one of your birds dies unexpectedly, don't perform a "backyard autopsy." Contact your local vet or agricultural extension office.

Support Testing Initiatives

Public health isn't just for doctors. Supporting policies that protect farmworkers and provide them with sick leave and healthcare access is a literal defense mechanism for the rest of society. The better we take care of the people on the "front lines" of animal contact, the less likely a mutation is to slip through the cracks.

Get Your Seasonal Flu Shot

This sounds counterintuitive because the seasonal flu shot doesn't protect against H5N1. However, it prevents "reassortment." If a person gets infected with regular human flu and bird flu at the same time, the two viruses can swap segments of their DNA. This is a nightmare scenario that could create a brand-new, highly contagious pandemic strain. By getting your regular flu shot, you’re reducing the chance of being that "mixing vessel."

The story of bird flu human transmission is still being written. It’s a slow-motion event that requires vigilance, not hysteria. We are currently in a window of opportunity where we can monitor the virus and prepare vaccines (the US has a small stockpile of H5N1-specific vaccines already) before the virus makes its next move. Staying aware of the facts—and ignoring the doom-scrolling—is the best way to navigate the current landscape.