Big Tupper isn't just a pile of rock and overgrown trails. It’s a mood. If you drive through the Adirondacks today, past the town of Tupper Lake, you might see the skeletal remains of chairlifts haunting the side of Mount Morris. It’s quiet. Way too quiet for a place that once boasted some of the best vertical drops in the Northeast. People around here don't just talk about Big Tupper ski mountain as a defunct business; they talk about it like a lost family member. It’s complicated, messy, and deeply tied to the identity of a town that refuses to let the dream die.

Honestly, the story of Big Tupper is a masterclass in how small-town passion can clash with massive development egos.

Opened back in 1960, it was the town's pride. It wasn't the glitzy, Olympic-fueled machine of Lake Placid's Whiteface. It was different. Locals loved it because it was steep, cheap, and lacked the three-hour lift lines. But the financial reality of running a mid-sized ski hill in a world of escalating climate unpredictability and corporate consolidation eventually caught up. It’s been "closed" more often than it’s been open over the last twenty-five years, leaving a gaping hole in the local winter economy.

The Adirondack Club and Resort Drama

You can't talk about Big Tupper ski mountain without mentioning the Adirondack Club and Resort (ACR). This was supposed to be the "Great Savior." The plan was massive. We're talking hundreds of luxury homes, a renovated ski area, and a total transformation of the Tupper Lake landscape. It sounded great on paper. In reality? It became a decade-long legal quagmire that basically froze the mountain in time.

Preservation groups like Protect the Adirondacks! fought the development tooth and nail. They weren't necessarily against skiing, but they were terrified of the environmental impact of such a sprawling residential project in the heart of the Adirondack Park. The lawsuits flew. The years ticked by. While lawyers argued in polished offices, the chairlifts on Mount Morris started to rust. The lodge, once full of the smell of wet wool and greasy fries, sat cold.

The developers, Michael Towne and Tom Lawson, faced an uphill battle from day one. Financing a project of that scale in a remote part of Northern New York is a nightmare. Even after they cleared the legal hurdles and got the Adirondack Park Agency (APA) permits, the money didn't just flow in. It’s a cautionary tale. If you’re looking for why Big Tupper isn't currently spinning its lifts, the ACR's stagnation is the primary culprit. It was a "go big or go home" strategy that, unfortunately, resulted in everyone going home.

What it was actually like to ski Big Tupper

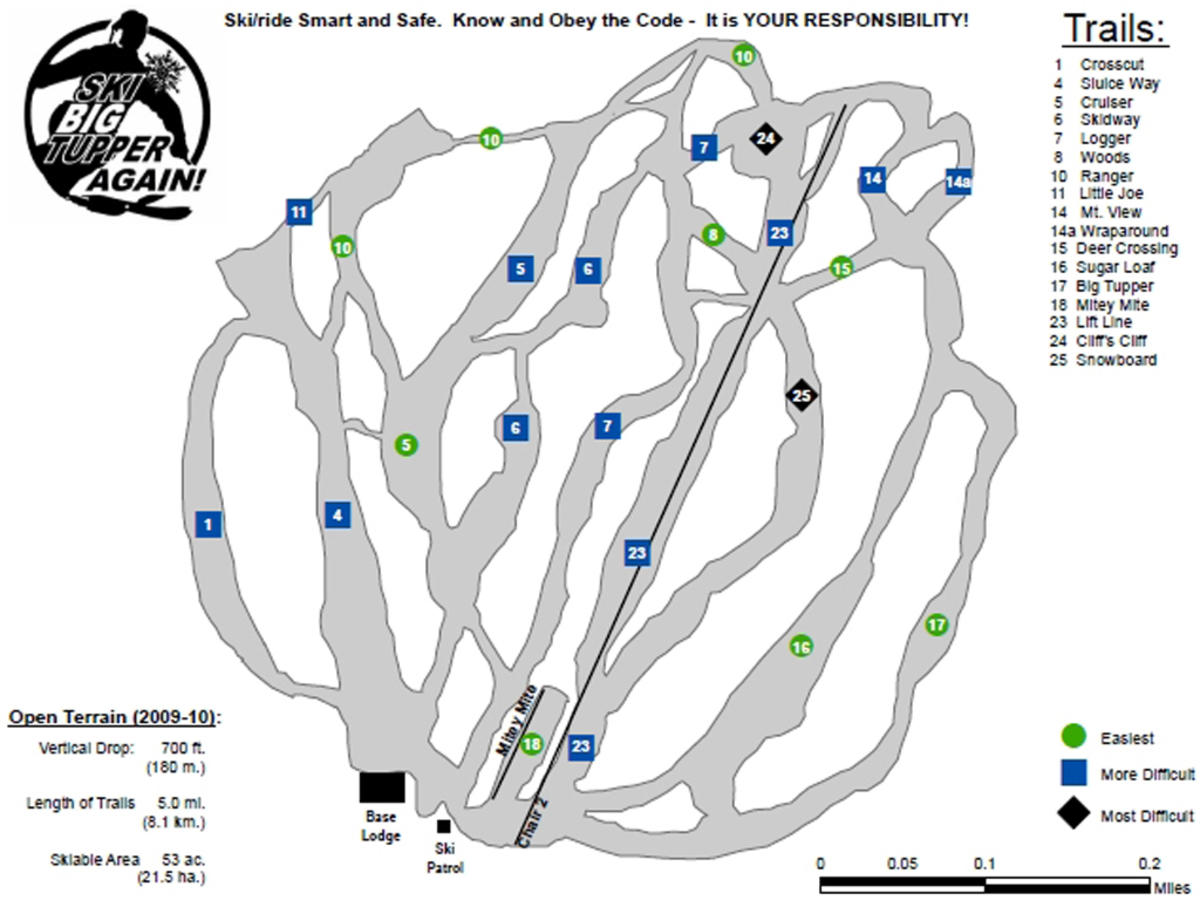

Let’s get nostalgic for a second. If you were lucky enough to hit Big Tupper on a powder day in the 80s or 90s, you knew. The mountain has a 1,152-foot vertical drop. That’s not massive compared to the Rockies, but in the East, it’s respectable. Especially when you consider the terrain.

🔗 Read more: Hernando Florida on Map: The "Wait, Which One?" Problem Explained

It was rugged.

- Chair 2 was the legendary one. It took you to the summit where the wind would absolutely whip off Tupper Lake, freezing your goggles instantly.

- The trails weren't over-groomed carpets. They had character. You’d hit a patch of ice, then a drift of lake-effect snow, then a stray branch.

- It felt wild.

The community vibe was the real draw. You didn't have to be a millionaire to ski there. It was the kind of place where the lift op knew your name and your dad’s name. In the mid-2010s, a group of volunteers called "Big Tupper Skiers" actually managed to reopen the mountain on a shoestring budget. They raised money through bake sales and local donations. They literally cleared the brush by hand. For a few glorious seasons, Big Tupper was a volunteer-run miracle. It proved the demand was there. People wanted to ski Tupper. They just needed a mountain that worked.

The current state of the mountain

If you head there right now, don't bring your skis unless you're prepared to "earn your turns" by skinning up. The lifts are strictly NOP (Not Operating). The property has been mired in tax foreclosures and legal disputes involving Franklin County. In 2021, there was a glimmer of hope when the county looked to sell the parcels to clear back taxes.

The reality of Big Tupper ski mountain today is a mix of "No Trespassing" signs and crumbling infrastructure. It’s heartbreaking for the town. Tupper Lake has been trying to reinvent itself as a year-round destination—the Wild Center is a world-class natural history museum right down the road—but a dead ski mountain is a hard thing to pivot away from.

Is it coming back? That’s the million-dollar question. Every few years, a new rumor floats through the local bars. "A group from Vermont is looking at it." "A billionaire wants a private club." "The state is going to buy it and turn it into a cross-country park."

Most of it is just talk. The cost to get those lifts back to modern safety standards is astronomical. We're talking millions just to get the cables turning, let alone the snowmaking infrastructure. Snowmaking is the real killer. Without a massive, modern system, you can't survive a modern Adirondack winter. The thaw-freeze cycles are too brutal now.

💡 You might also like: Gomez Palacio Durango Mexico: Why Most People Just Drive Right Through (And Why They’re Wrong)

Why we should care about "Lost" ski areas

Big Tupper isn't alone. It’s part of a growing list of "lost" ski areas across North America. But it represents something specific: the loss of the "middle class" ski experience. When places like Big Tupper close, skiing becomes a sport reserved for the wealthy who can afford the $200 day passes at corporate-owned mega-resorts.

There's also the ecological perspective. Some argue that letting the mountain return to nature is the best outcome. The forest is reclaiming the trails. Deer and bear now roam where teenagers used to drink hot cocoa. But that ignores the human ecology. A town like Tupper Lake needs an anchor. It needs a reason for people to stop instead of just driving through on their way to Saranac Lake or Long Lake.

The struggle of Big Tupper ski mountain highlights the tension between private development and public benefit. Should the state intervene? New York already owns and operates Whiteface, Gore, and Belleayre through the Olympic Regional Development Authority (ORDA). Adding a fourth mountain to the taxpayer's tab is a tough sell politically, especially one that needs as much work as Big Tupper.

Actionable steps for the Adirondack traveler

Even though the lifts aren't spinning, the area around the mountain is still worth your time. If you’re a fan of "ski archaeology" or just want to support the Tupper Lake community, here is what you can actually do:

1. Hike the nearby peaks. Mount Arab and Coney Mountain are short, punchy hikes with incredible views of the Tupper Lake chain. You can see the footprint of the ski mountain from the top of Arab. It gives you a sense of the scale of the landscape.

2. Visit the Wild Center. If you want to understand the ecology of the mountain, this is the place. It’s one of the best museums in the country, and their "Wild Walk" lets you walk through the treetops. It's the economic engine keeping the town afloat while the mountain sleeps.

3. Support local businesses like Raquette River Brewing. The brewery is a hub for the community. Talk to the locals there. You'll hear the real stories about Big Tupper—the ones that aren't in the news reports. It’s where the "Big Tupper Skiers" volunteers used to gather.

4. Respect the property. It’s tempting to go exploring the old lodge or climbing the lift towers. Don't. It's private property, it's unsafe, and it's heavily monitored. Local law enforcement doesn't take kindly to "urban explorers" messing with what's left of the mountain's dignity.

5. Keep an eye on Franklin County tax auctions. If you’re a developer with a heart of gold and a very large bank account, this is where the future of the mountain will be decided. The legal status of the land is always shifting.

Big Tupper ski mountain remains a symbol of Adirondack grit. Whether it ever reopens as a commercial ski resort or eventually transitions into a community forest or a state-managed backcountry area, its impact on the region is permanent. It’s a reminder that mountains are more than just terrain—they’re repositories for a community's memories and its hopes for the future. For now, the mountain waits.

To truly understand the region, look beyond the "Closed" signs. Look at the lake, the surrounding forests, and the people who still wear their vintage Big Tupper patches with pride. The mountain hasn't moved; only the dream has changed shape.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

If you want to stay updated on the legal status of the mountain, follow the Tupper Lake Free Press or the Adirondack Explorer. These local outlets provide the most granular detail on the ongoing land disputes and potential sales. For those interested in the history of defunct hills, the New England Lost Ski Areas Project (NELSAP) maintains a detailed archive of Big Tupper’s operational history, including vintage trail maps and photos from its heyday. Supporting the Adirondack Sky Center & Observatory in Tupper Lake is another great way to invest in the town's future as a "dark sky" destination, providing an alternative to the traditional ski-town model.