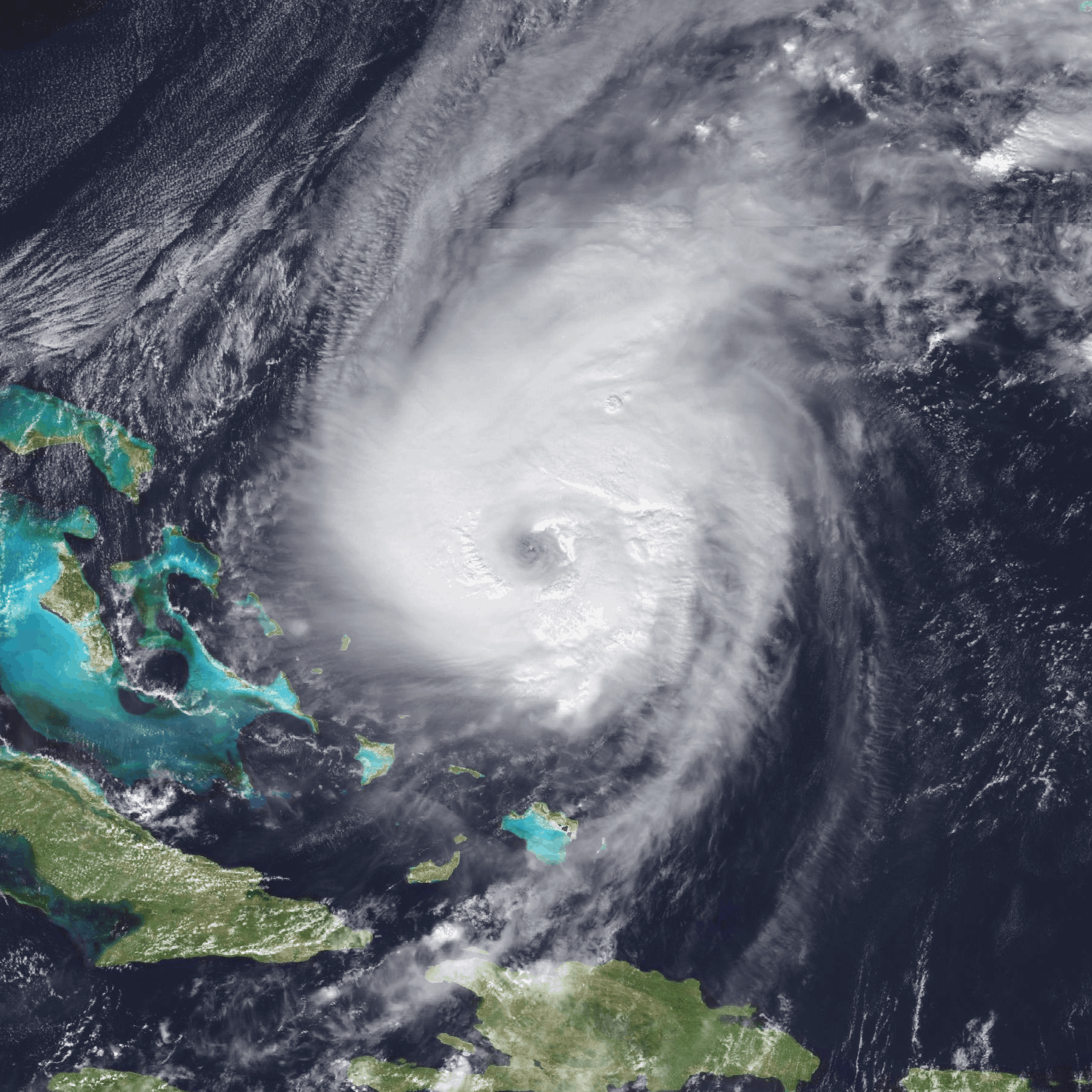

You’ve seen the footage. The shaky cell phone video of a stop sign vibrating in 150 mph winds before it snaps like a toothpick. The aerial shots of New Orleans or Fort Myers looking more like a lake than a neighborhood. Honestly, when we talk about big hurricanes in the US, we usually jump straight to the wind speed or the "Category" number. But if you talk to any meteorologist at the National Hurricane Center (NHC) in Miami, they’ll tell you that the Saffir-Simpson scale—that 1 to 5 ranking—is kind of a blunt instrument. It doesn't measure water. And water is what kills.

Big storms are changing. They aren’t just getting "stronger" in a linear way; they’re behaving differently. They’re stalling. They’re dumping trillions of gallons of rain on inland cities that thought they were safe. If you’re just looking at the wind, you’re missing the real threat.

The monsters we can't forget

Think back to 2005. Hurricane Katrina wasn't even a Category 5 when it hit the Gulf Coast; it was a Category 3. But the sheer size of the wind field had already pushed a massive wall of water toward the shore. That storm surge is what broke the levees. It wasn’t just a "big hurricane"; it was a failure of engineering meeting a massive geophysical event. Over 1,800 people died. It changed the way the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) operates forever, though many would argue those changes haven't gone far enough.

Then you have the outliers like Hurricane Andrew in 1992. That one was different. It was small. Compact. Fast. It acted like a giant tornado that leveled Homestead, Florida. It was one of the few to be retroactively upgraded to a Category 5. If you lived through Andrew, the sound is what you remember—the sound of a freight train running through your living room.

Why name them?

We name these things because it makes them "real" to the public. Since 1953, the World Meteorological Organization has used lists of names to improve communication. It's a lot easier to say "Get ready for Helene" than "the tropical cyclone at 28.5 North, 82.3 West." But once a storm causes enough death or destruction—like Ian or Maria—the name is retired. It’s a hall of fame nobody wants to be in.

✨ Don't miss: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

The new era of big hurricanes in the US

The last decade has felt... heavier. 2017 was a nightmare year. You had Harvey, Irma, and Maria all in one season. Harvey was the wake-up call for the "stalling" phenomenon. It sat over Houston and just... poured. It dropped over 50 inches of rain in some spots. That’s more than some cities get in two years. It proved that a storm doesn't need 160 mph winds to be a "big" disaster. It just needs to stay still.

Climate scientists, like Dr. Michael Mann, have often pointed out that a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture. Specifically, for every 1 degree Celsius of warming, the air can hold about 7% more water vapor. You do the math. When these big hurricanes in the US pull from a Gulf of Mexico that is bathtub-warm, they are essentially vacuuming up fuel.

Rapid Intensification: The forecaster's nightmare

There is this thing called "Rapid Intensification" (RI). It’s defined as an increase in maximum sustained winds of at least 35 mph in 24 hours. Recently, we’ve seen storms like Hurricane Otis (which hit Acapulco) and Hurricane Ian explode in strength right before landfall. This is terrifying for emergency managers. If a storm is a Category 1 when people go to sleep and a Category 4 when they wake up, there’s no time to evacuate. The "hunker down" order becomes a survival gamble.

The geography of risk is expanding

It’s not just Florida and Louisiana anymore. Look at Hurricane Sandy in 2012. It wasn’t even technically a hurricane when it hit New Jersey; it was a "post-tropical cyclone." But it was massive. It shut down the New York City subway system and flooded the Financial District. It showed that the Northeast is incredibly vulnerable to the storm surge of these massive systems because the coastline is so densely populated and the infrastructure is old.

🔗 Read more: Passive Resistance Explained: Why It Is Way More Than Just Standing Still

And then there's the inland flooding. In 2024, Hurricane Helene showed that a storm hitting the Florida Panhandle can cause catastrophic, once-in-a-thousand-year flooding in the mountains of North Carolina. Thousands of feet above sea level, people were losing their homes to mudslides and river surges. The lesson? You don't need a beach house to be a victim of a hurricane.

The insurance crisis

Because of these massive losses, the business side of hurricanes is breaking. In Florida and California (though for different reasons), major insurers like State Farm and Farmers have pulled back. Reinsurance rates—the insurance that insurance companies buy—are skyrocketing. This isn't just a weather story; it’s a "can I afford my mortgage" story. If you can't get hurricane insurance, you can't get a loan. The economic footprint of these storms lasts decades longer than the actual wind.

Survival is about more than plywood

People used to think "I'll just board up the windows and buy some batteries." That doesn't cut it anymore. When we look at how to handle big hurricanes in the US, the focus has shifted to resilience.

- Hardening the grid: Moving power lines underground is expensive, but so is fixing them every three years.

- Green infrastructure: Instead of just concrete sea walls, cities are looking at "living shorelines"—mangroves and oyster reefs that absorb wave energy.

- Vertical evacuation: In some places, you can't get out in time. You need buildings designed to let the water flow through the bottom floor while people stay safe on the fourth.

The reality is that "The Big One" is a moving target. It might be a Category 5 wind event, or it might be a Category 2 rain event that doesn't leave for three days. Both are equally deadly.

💡 You might also like: What Really Happened With the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz

How to actually prepare for the next one

Forget the generic "buy water" advice. If you live in a hurricane-prone zone, or even a few hundred miles inland, you need to think like an expert.

First, know your elevation. Not your "general area," but your specific plot of land. If you are 5 feet above sea level and a storm is pushing a 10-foot surge, you have a math problem that plywood won't solve. Second, digitize everything. Take photos of every room in your house for insurance purposes and upload them to a cloud server. When the roof is gone, you won't find your paper receipts.

Third, understand the "cone of uncertainty." People look at the line in the middle of the NHC forecast and think that's where the storm is going. It's not. The storm can be anywhere in that cone, and the impacts—the rain, the tornadoes, the surge—extend hundreds of miles outside of it.

Actionable steps for the upcoming season

- Review your "Loss Assessment" coverage. If you live in a condo or HOA, and a hurricane hits the common areas, the association might charge every owner a fee to fix it. This coverage helps pay that bill.

- Install a manual transfer switch. If you have a portable generator, don't run extension cords through a cracked window (which lets in rain and fumes). A transfer switch is safer and lets you run your fridge and lights directly.

- Get a "dumb" phone or a battery-powered radio. When the towers go down, 5G is useless. NOAA weather radios are the only reliable way to get updates when the grid fails.

- Clean your gutters now. It sounds stupidly simple, but a lot of "hurricane flooding" starts because the house's own drainage system was clogged with leaves, forcing water under the shingles or into the basement.

The era of the "predictable" hurricane is over. We are now in the age of the "megastorm," where the labels we use to describe weather are struggling to keep up with the reality on the ground. Stay vigilant, stay informed, and don't trust the wind speed alone to tell you how dangerous a storm is.