You're staring at a whiteboard or a LeetCode screen. The clock is ticking. You know you need to traverse a graph, and the choice between Breadth-First Search and Depth-First Search feels like a coin flip. But then comes the kicker: "What's the efficiency?" Understanding bfs and dfs time complexity worst case isn't just about memorizing a formula for an interview. It’s about knowing how your code will behave when the data gets messy, huge, and unmanageable.

Honestly, most people just parrot $O(V + E)$ and call it a day. But why? What does that actually mean when you're staring at ten million nodes?

The Big Picture of V and E

Before we dive into the weeds, let's get the terminology straight. In graph theory, $V$ represents the number of vertices (the nodes or points), and $E$ represents the edges (the connections between them).

When we talk about bfs and dfs time complexity worst case, we are essentially asking: "If I have to look at everything because the thing I'm searching for is in the very last place I'll look—or isn't there at all—how much work am I doing?"

Both algorithms, at their core, are exhaustive. They don't skip stuff unless you tell them to.

Breadth-First Search: The Rippling Pond

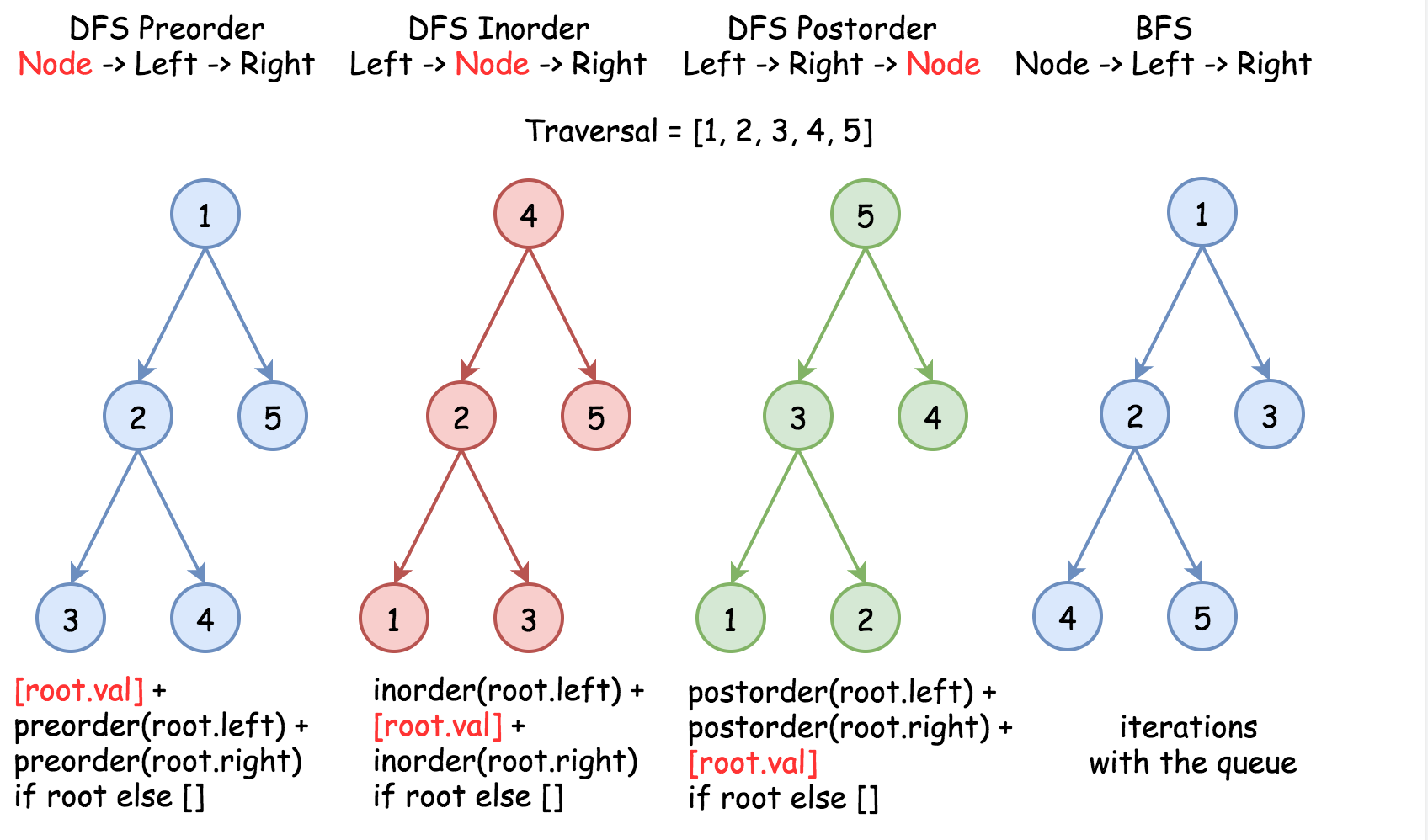

Think of BFS like dropping a stone in a still lake. The ripples go out one level at a time. It explores all neighbors at distance 1, then all neighbors at distance 2, and so on.

In the absolute worst-case scenario for BFS, you have to visit every single vertex and traverse every single edge to realize the node you want isn't there. You're hitting every $V$. And for every node you visit, you have to check all its neighbors. That's where $E$ comes in.

💡 You might also like: B-2 Spirit Top Speed: Why It Is Actually Slower Than Your Last Vacation Flight

If you're using an adjacency list, the complexity is $O(V + E)$.

Why? Because you touch every vertex once when you dequeue it, and you iterate through the adjacency list of each vertex exactly once. Summing up the lengths of all adjacency lists in a directed graph gives you $E$. In an undirected graph, it’s $2E$, but we drop constants in Big O. It's simple.

But wait. What if you're using an adjacency matrix?

This is a common trap. If you have a matrix, for every single vertex, you have to scan an entire row of length $V$ to find its neighbors. That makes the complexity $O(V^2)$. If your graph is sparse (not many edges), using a matrix is a performance nightmare. You’re spending time looking at "empty" edges that don't even exist.

Depth-First Search: The Dark Alleyway

DFS is different. It’s the "bold" explorer. It picks a path and runs down it until it hits a dead end or the target. Only then does it backtrack.

The bfs and dfs time complexity worst case remains identical here: $O(V + E)$ for adjacency lists.

You might think DFS is faster because it "dives," but in the worst case—say, a path that leads to the very last node in the graph—you still see everything. You visit every vertex. You check every edge.

There's a subtle nuance here regarding memory, though. While the time complexity is the same, the space complexity behaves differently. BFS uses a queue and can get very "wide" (storing an entire level of a tree), whereas DFS uses a stack (or recursion) and gets "deep." In a very deep tree, DFS might hit a stack overflow. In a very wide tree, BFS might eat all your RAM.

When the "Worst Case" Hits Hard

Let's look at a real-world example. Imagine you're building a crawler for a social network like LinkedIn to find a "6th-degree connection."

If you use BFS, the bfs and dfs time complexity worst case is felt when that person doesn't exist in your network. You will literally index millions of people (vertices) and hundreds of millions of connections (edges) before the algorithm finally says "Not found."

In a dense graph, where $E$ approaches $V^2$, your "linear" $O(V + E)$ starts looking a lot more like $O(V^2)$. This is why engineers at companies like Google or Meta don't just run raw BFS/DFS on the whole global graph. They use heuristics, sharding, and bounded searches.

Misconceptions About Edge Cases

A lot of students think that if a graph is disconnected, the complexity changes. It doesn't.

If you have a graph with two separate islands of nodes and you start a search on Island A, you'll never see Island B. Technically, you only visited $V_{subset}$ and $E_{subset}$. However, the algorithm description for a full traversal usually includes a loop over all vertices to ensure every component is visited. If you include that loop, you are back to $O(V + E)$.

✨ Don't miss: Power Station Cooling Towers: Why Those Giant Concrete Chimneys Don't Actually Smoke

Another point of confusion: Weighting.

If your edges have weights (like distances on a map), BFS and DFS are no longer the right tools for finding the "shortest" path. You'd move to Dijkstra’s or A*. But for raw reachability—just asking "can I get there?"—the bfs and dfs time complexity worst case remains the gold standard of measurement.

Implementation Details That Break Your Complexity

I've seen senior devs mess this up. They use a list instead of a proper Queue (like a deque in Python) for BFS.

If you use a standard list and pop(0) in Python, that operation is $O(N)$. Suddenly, your BFS isn't $O(V + E)$ anymore. It becomes $O(V^2 + E)$ because every time you pull a node out of the queue, you're shifting every other element in memory.

Always use:

- BFS: A true FIFO queue (collections.deque in Python, Queue in Java).

- DFS: A LIFO stack or recursion (just be mindful of recursion limits).

- Visited Set: A Hash Set (O(1) lookup) to keep track of where you've been. If you use a list to track visited nodes and do

if node not in visited_list, you've just turned your $O(V+E)$ algorithm into an $O(V^2)$ disaster.

Choosing Your Weapon

So, if the worst-case time is the same, how do you choose?

📖 Related: Create Apple account free: What you actually need to know about the process

Basically, it comes down to the shape of the data and what you're looking for. Use BFS if you want the shortest path in an unweighted graph (like "fewest clicks to get to a Wikipedia page"). Use DFS if you need to visit everything anyway—like solving a maze or checking for cycles—and want to keep the memory footprint lower on narrow graphs.

The bfs and dfs time complexity worst case is a reminder that computers aren't magic. They have to do the work. Whether you go wide or go deep, if the answer is at the very end, you're paying the full price of $V$ and $E$.

Actionable Steps for Optimization

To keep your search algorithms running at peak performance, follow these technical guidelines:

- Audit Your Data Structure: If your graph is sparse (most nodes have only a few connections), stick with an adjacency list. If it's incredibly dense (almost every node connects to every other node), an adjacency matrix might actually be faster due to cache locality, despite the $V^2$ overhead.

- Verify Queue/Stack Efficiency: Ensure your

popoperations are $O(1)$. In Python, usefrom collections import deque. In C++,std::queueorstd::stackare your friends. - Use Hash-Based Tracking: Never use a list to track visited nodes. Use a

Setor a boolean array of size $V$. Checkingif node in visited_setmust be $O(1)$. - Early Exit: While the worst case assumes you visit everything, always include a conditional break the moment your target is found. It won't change the Big O, but it will change your real-world execution time.

- Iterative over Recursive for DFS: If you're dealing with deep graphs (like a linked list disguised as a tree), use an iterative DFS with an explicit stack to avoid

StackOverflowErrororRecursionError.

By strictly adhering to $O(1)$ lookups for visited nodes and using the correct queue/stack structures, you guarantee that your implementation matches the theoretical $O(V + E)$ limit.