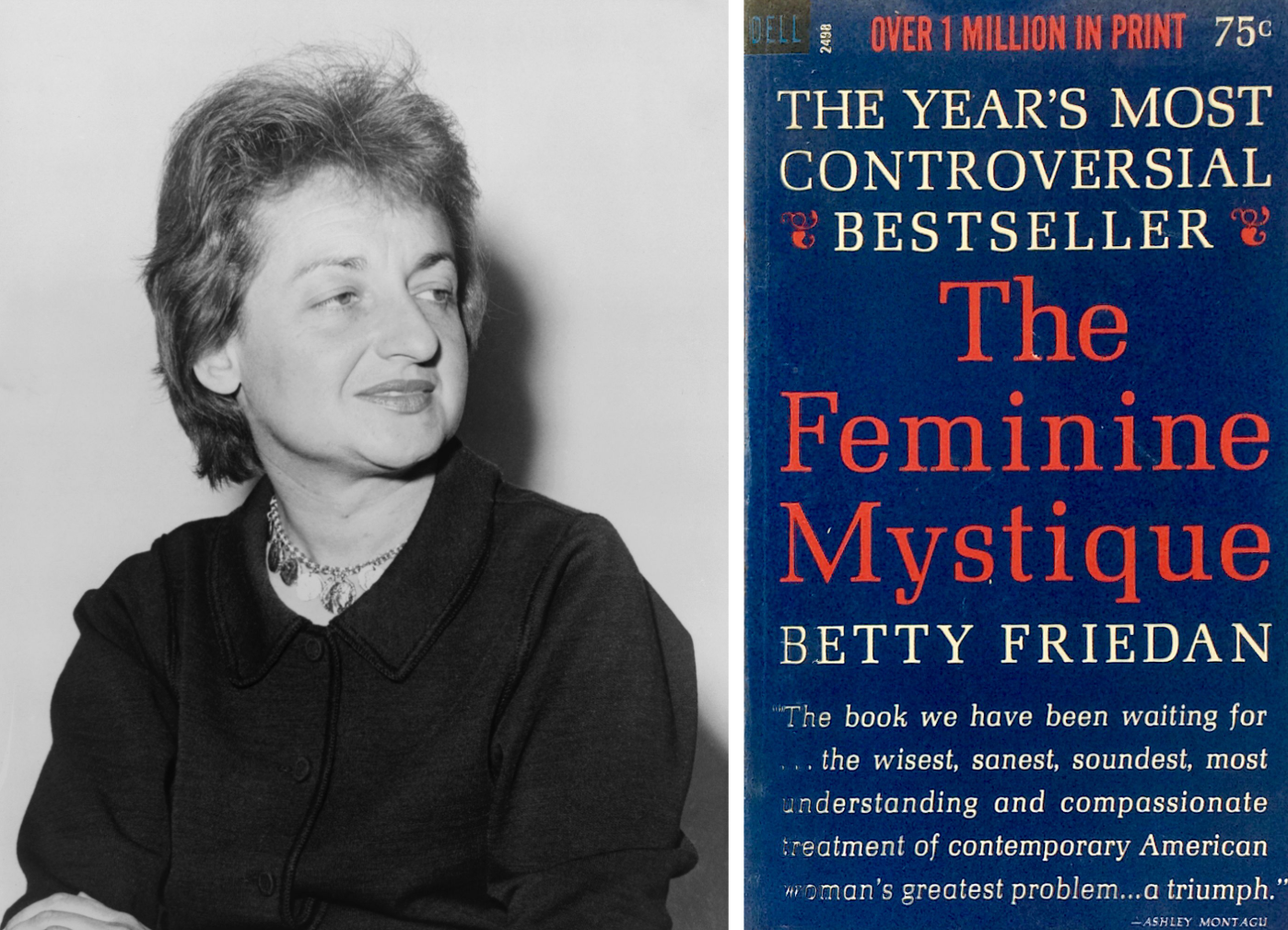

Ever walked through a perfectly clean house, looked at your reflection in a shiny toaster, and thought, "Is this actually it?" That specific, hollow ache is exactly what Betty Friedan tapped into back in 1963. She called it "the problem that has no name," and honestly, it’s a vibe that hasn't totally left the building, even sixty years later.

When The Feminine Mystique first landed on nightstands, it didn't just ruffle feathers; it basically set the coop on fire. You've got to remember the 1950s and early 60s weren't just about poodle skirts and milkshakes. For a lot of women, it was a period of high-key cultural gaslighting. They were told that if they had a husband, a suburban home, and a vacuum cleaner, they’d reached the peak of human happiness. If they felt miserable? Well, that was a "personal" problem. Probably needed more antidepressants or a better rug-hooking class.

Friedan changed the game by saying, "Nah, it’s not you. It’s the system."

Breaking Down The Feminine Mystique

Basically, the "mystique" was this pervasive myth that a woman's only path to fulfillment was through being a wife and mother. Period. Friedan argued that this narrow ideal was actually "burying millions of women alive." She didn't just pull this out of thin air, either. She was a powerhouse journalist—graduated summa cum laude from Smith College—who spent five years interviewing housewives and tracking how the "independent woman" of the 1930s had been replaced by a passive, domestic doll.

The Weird Reality of 1963

It’s kinda wild to look at the stats Friedan dug up. In the late 50s, the average age of marriage for women was dropping—sometimes down to 17 or 18. Girls were literally going to college just to get an "M.R.S. degree."

📖 Related: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

Friedan’s research pointed out some pretty predatory stuff:

- Advertising: Ads for children's dresses (sizes 3-6x!) were marketed with slogans like "She Too Can Join the Man-Trap Set."

- Education: Schools were steering girls away from physics and toward "home economics" to ensure they didn't become "unfeminine."

- Pseudo-Science: She went after Freud’s "penis envy" theory, basically calling it a scientific excuse for sexism.

She described the suburban home as a "comfortable concentration camp." Yeah, that’s a heavy metaphor. She actually regretted using it later in life, but at the time, she wanted to convey the psychological death that happens when your brain is never allowed to stretch beyond the grocery list.

What Most People Get Wrong About Betty Friedan

A lot of folks think Friedan hated stay-at-home moms or wanted everyone to burn their bras. (Fun fact: the bra-burning thing is mostly an urban legend from the 1968 Miss America protest). Honestly, Friedan wasn't against marriage or kids. She had three kids herself! What she hated was the lack of choice.

She argued that women needed "creative work" of their own. She famously said, "No woman gets an orgasm from shining the kitchen floor." It sounds funny now, but it was a radical truth-bomb back then. She believed that when women were denied a chance to grow, they became "smothering" mothers because they were trying to live vicariously through their kids. It was a lose-lose for everyone.

👉 See also: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

The "Lavender Menace" and Other Flaws

We have to be real here: Friedan wasn't perfect. Not even close. She’s often criticized today for focusing almost exclusively on white, middle-class, educated women. If you were a Black woman in the 60s, "the problem that has no name" wasn't your biggest issue—you were dealing with systemic racism and likely already working outside the home out of necessity.

Friedan also had a major blind spot regarding the LGBTQ+ community. She notoriously called lesbian activists the "lavender menace," fearing they’d make the feminist movement look too radical or "man-hating." She eventually walked some of this back in the late 70s, but it remains a messy part of her legacy.

Why The Feminine Mystique Still Matters in 2026

You’d think a book written when people still used rotary phones wouldn't matter anymore. But look at "TradWife" TikTok or the "Soft Life" aesthetic. There’s still this weird, recurring pressure to find total bliss in domesticity, often as a reaction to how exhausting the modern workplace is.

Friedan’s core message—that you are a human being first and a "role" second—is still the foundation of how we talk about mental health and identity today. She helped found NOW (National Organization for Women) and fought for the Equal Rights Amendment. She pushed for child care and reproductive rights because she knew that "personal growth" is impossible if you’re legally and financially shackled.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Blue Jordan 13 Retro Still Dominates the Streets

Actionable Insights for Today

If you’re feeling that "is this all?" sensation, Friedan’s work offers a few timeless moves:

- Audit the "Mystique" in your life. Are you doing things because you love them, or because a social media algorithm told you that "aesthetic" is what a happy person looks like?

- Find your "Creative Work." This doesn't have to be a 9-to-5. It’s about having a project or a pursuit that is yours alone, where you aren't "someone's mom" or "someone's partner."

- Recognize the "Invisible Labor." Friedan pointed out that housework expands to fill the time available. If you're spending four hours "curating" a pantry, ask yourself if that's actually bringing you joy or just filling a void.

- Connect. The biggest power of The Feminine Mystique was showing women they weren't alone. Isolation is the enemy of change.

The world has changed a lot since Betty Friedan sat at her kitchen table in New York and started typing. We have more rights, more seats at the table, and way better vacuums. But the struggle to be seen as a full, complex human being—rather than just a series of functions for other people—is a fight that’s still very much alive.

To truly understand the modern world, you have to look back at the moment the silence was finally broken. Reading the book today is less like a history lesson and more like a mirror. It’s a reminder that "the problem that has no name" only stays powerful as long as we’re afraid to talk about it.