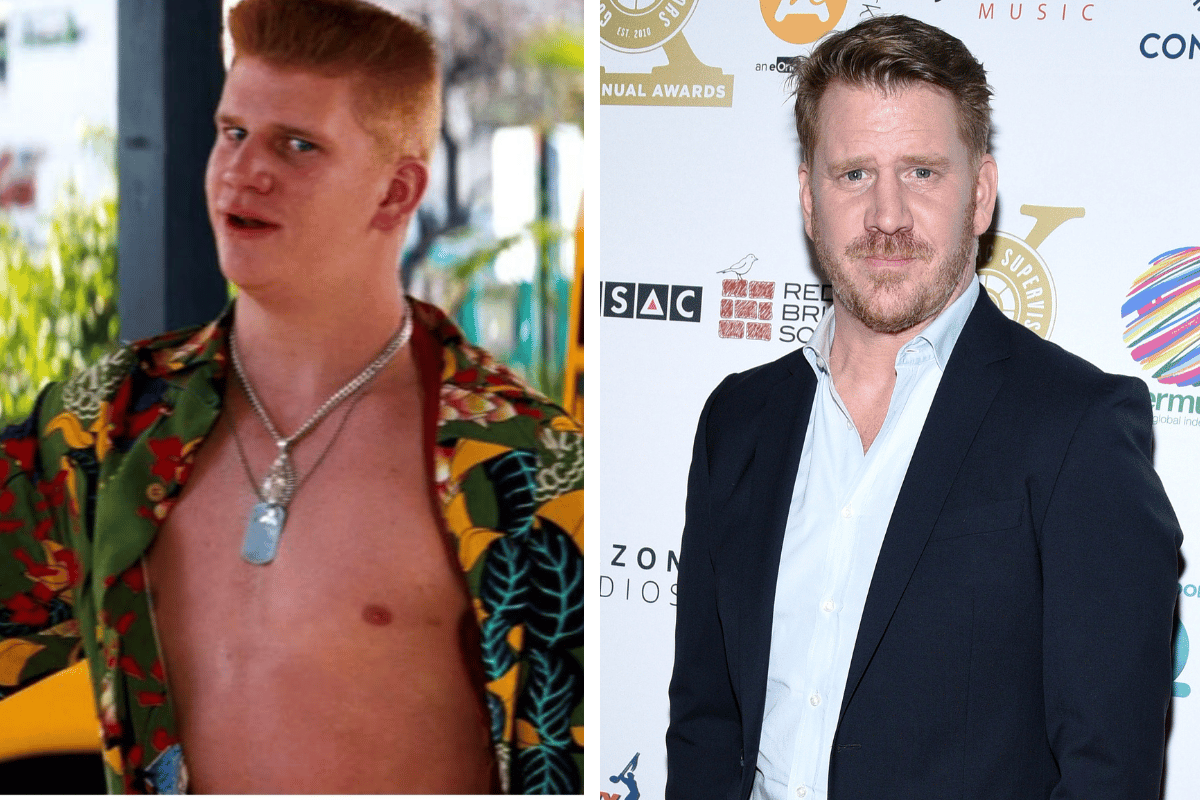

Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 fever dream of a movie didn't just modernize Shakespeare; it electrified it. You remember the neon crosses, the Hawaiian shirts, and the "Sword 9mm" pistols. But while everyone was staring at Leo’s hair or Claire Danes’ wings, Benvolio in Romeo and Juliet 1996 was quietly doing the heaviest lifting in the background. Dash Mihok played him not as some stuffy stage actor, but as a sweaty, anxious, and deeply loyal kid caught in a corporate war he clearly hated.

He's the first face we really get a look at during that iconic gas station shootout. Honestly, his pink hair and frantic energy set the tone for the whole flick. While the rest of the Montagues were busy being "Young Guns," Benvolio was the one actually trying to keep the peace, which is exactly what his name means in Latin: "well-wishing."

The Pink Hair and the 9mm: Reimagining the Peacekeeper

In the original text, Benvolio is often played as a bit of a bore. He’s the "good" one. But Luhrmann and Mihok turned him into a frantic, relatable teenager. You've got this guy wearing a loud shirt and sporting a buzzcut that looks like it was dyed in a sink, yet he’s the only one with his head screwed on straight. When he yells "Put up your swords!" it’s not a polite request. In Verona Beach, it’s a desperate plea to avoid a literal massacre in a crowded public space.

Mihok’s performance is twitchy. It’s grounded. Unlike Tybalt, who moves like a flamenco dancer with a death wish, Benvolio moves like a guy who knows he’s probably going to get shot. This version of the character highlights the tragedy of the peacemaker in a violent society. He is constantly trying to de-escalate, but the gravity of the feud just pulls him back in. It’s a thankless job. He spends half the movie looking like he needs a nap and a cigarette, which feels way more authentic to the "Verona Beach" vibe than a stoic nobleman.

Why the 1996 Version Hit Different

Most people forget that Benvolio is the one who basically starts the whole plot by convincing Romeo to go to the Capulet party. In the 1996 film, this scene takes place at a dilapidated theater on the beach. It’s gritty. You can almost smell the salt air and the cheap gasoline. Benvolio isn't just giving advice; he’s trying to snap his best friend out of a depressive funk.

- He sees Romeo moping.

- He suggests checking out other "beauties."

- He unintentionally sets the fuse for the entire tragedy.

It’s ironic, right? The guy who wants peace the most is the catalyst for the ultimate catastrophe. Dash Mihok plays this with a sort of frantic brotherhood. He’s not a mentor; he’s a peer. That’s a huge distinction that makes the 1996 version work so well for a younger audience.

✨ Don't miss: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

The Tragedy of Being the Last One Standing

One of the most heartbreaking things about Benvolio in Romeo and Juliet 1996 is what happens toward the end. Or rather, what doesn't happen. In many stage productions, Benvolio just sort of vanishes after Mercutio and Tybalt die. He delivers the news to the Prince (or the "Captain of Police" in this case, played by Vondie Curtis-Hall) and then he’s gone.

But in the movie, his presence—or the lack of his ability to stop the carnage—feels heavier. He’s the witness. He has to watch his best friend get banished. He has to see the body of Mercutio on the sand. There’s this specific shot of him looking absolutely devastated as the storm rolls in. It’s a realization that his "well-wishing" didn't mean a damn thing in the face of ancient grudges.

He’s a survivor, but in a Shakespearean tragedy, being the survivor is its own kind of trauma. He has to carry the story. He’s the one who tried to stop the fight at the start, and he’s the one left looking at the wreckage at the end.

Dash Mihok’s Impact on the Role

Let's talk about the acting for a second. Dash Mihok wasn't a huge name at the time, which actually helped. He didn't have the "movie star" aura that DiCaprio had. He felt like a real guy you'd know. His chemistry with Harold Perrineau (Mercutio) was electric. While Mercutio was the chaotic center of the group, Benvolio was the anchor.

If you watch the scene where they’re getting ready for the party, Mihok plays it with this sort of "I can't believe we're doing this" grin. He's the audience surrogate. He knows this is a bad idea, but he loves his friends too much to let them go alone. That’s the core of the character. Loyalty over logic.

🔗 Read more: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

The Visual Language of the Montague Boys

Luhrmann used costume design to tell us everything we needed to know about the social hierarchy. The Capulets were sleek, dressed in black leather and Dolce & Gabbana-inspired gear. They looked like professional killers. The Montagues? They were a mess of color.

Benvolio’s wardrobe—unbuttoned shirts, sagging pants, and that shock of pink hair—symbolized a sort of rebellious innocence. He wasn't trying to be a soldier. He was just a kid in a loud shirt. This visual choice makes the violence against them feel even more jarring. When Tybalt kicks Benvolio in the gas station, it’s a bully attacking a kid who just wants to go home.

Misconceptions About Benvolio's Role

A lot of people think Benvolio is just a secondary character who doesn't matter much. That’s a mistake. Without him, there is no foil to Tybalt. If Tybalt is "fire," Benvolio is "water." He’s there to show us what the world could look like if everyone just took a breath and calmed down.

In the 1996 film, this is emphasized by the frenetic editing. Whenever things get too fast, the camera often cuts back to Benvolio’s face. He looks worried. He’s the moral barometer. When he looks scared, the audience knows they should be scared too. He’s not a coward; he’s the only one who is actually paying attention to the stakes.

Key Moments to Rewatch

If you’re going back to watch the movie, pay attention to these specific beats:

💡 You might also like: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

- The Gas Station: Watch how he tries to hide his gun and talk Tybalt down. He’s genuinely terrified not for himself, but for what’s about to happen to the city.

- The Sycamore Grove: The way he approaches Romeo. It’s tender. It’s not the way "macho" guys are usually allowed to interact in movies.

- The Mercutio Death Scene: His reaction is visceral. It’s not a "movie" cry; it’s a "my friend is dying in the dirt" cry.

Actionable Takeaways for Film Students and Fans

If you're studying the film or just a die-hard fan, understanding Benvolio's function helps decode Luhrmann’s entire "Red Curtain" style. Here is how to look at it:

- Analyze the Blocking: Notice how Benvolio is often placed between characters who are about to fight. He physically tries to be the barrier.

- Contrast the Acting Styles: Compare Mihok’s naturalistic, twitchy performance with John Leguizamo’s highly stylized, almost operatic Tybalt. It shows the divide between someone who wants to live and someone who wants to be a legend.

- Color Theory: Think about how his pink hair contrasts with the orange and yellow of the explosions and the blue of the Verona Beach ocean. He stands out as a beacon of "softness" in a "hard" world.

To really appreciate what Mihok did, you have to look past the 90s aesthetic. He turned a functionary character into a soulful, breathing person. He showed that even in a world of "Sword 9mms" and corporate warfare, there’s still room for a guy who just wants his friends to be okay.

Next time you put on the soundtrack—which is still a banger, by the way—think about the guy in the pink hair. He was the only one trying to save everyone from the very beginning.

What to Do Next

- Watch the 1996 Opening Scene Again: Specifically, count how many times Benvolio tries to stop the fight before a shot is actually fired.

- Compare to the 1968 Zeffirelli Version: Notice how Bruce Robinson’s Benvolio is much more composed and "noble." It makes you realize how radical Mihok’s "anxious teen" interpretation really was.

- Read the First Scene of the Play: Look at Benvolio's lines. You'll see that almost every word out of his mouth is about peace, yet he's constantly ignored. It’s a masterclass in tragic characterization.

Understanding Benvolio changes the way you see the entire Montague family. They aren't just "the other side" of the feud; they're a group of kids who, led by Benvolio's example, might have actually found a way out if the world hadn't been so hell-bent on burning down.