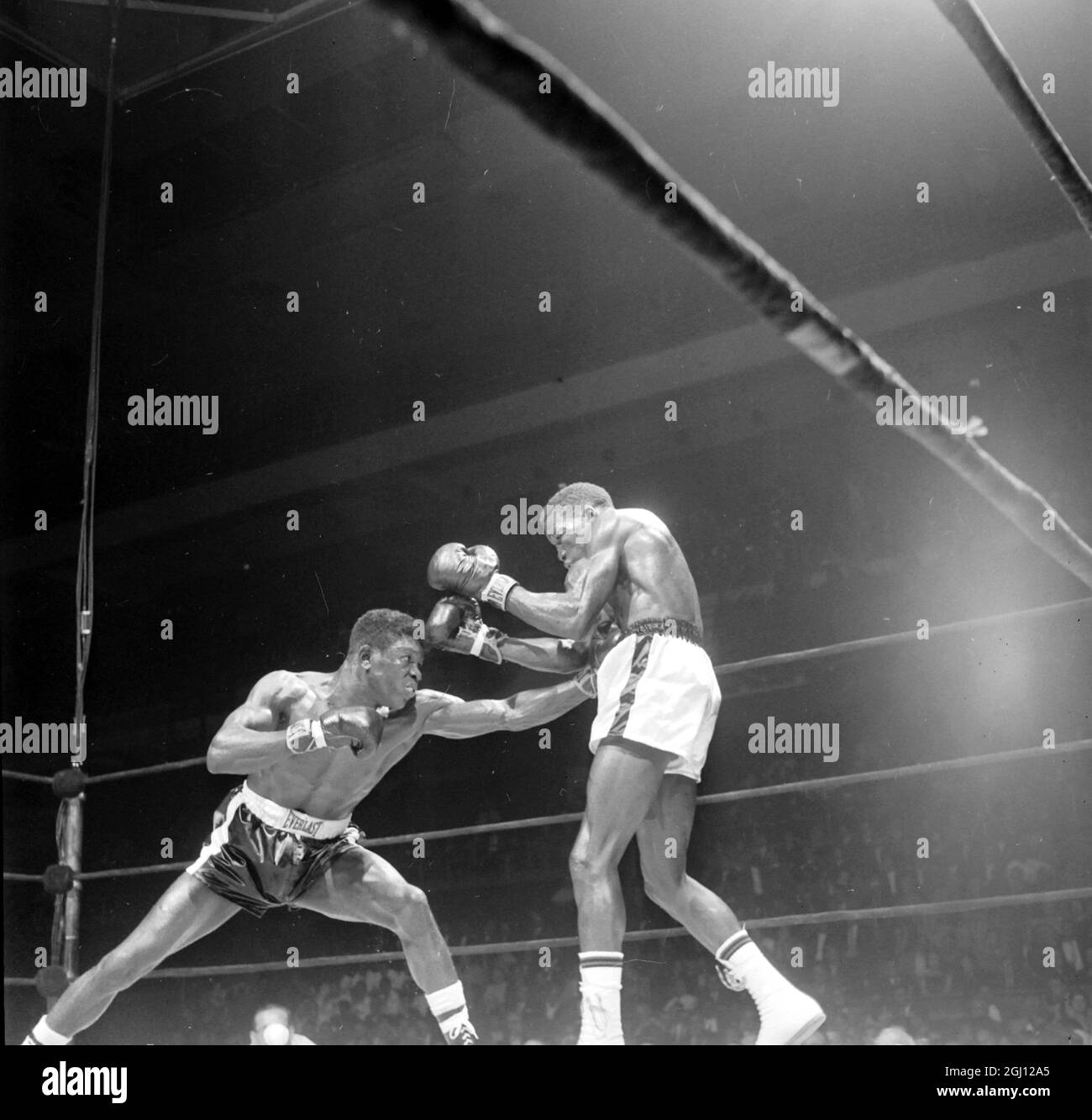

March 24, 1962. A Saturday night at Madison Square Garden. The air smelled of cigar smoke and sweat, the kind of atmosphere that defined old-school boxing before it became a polished corporate product. Emile Griffith was standing in the ring, his muscles coiled, facing a man he had come to truly despise. Across from him stood Benny Paret, the Cuban champion they called "The Kid."

The fight was being broadcast live on ABC’s Fight of the Week. Millions of people were tuned in from their living rooms, watching on grainy black-and-white sets. They didn't know they were about to witness a slow-motion execution.

The Slur That Changed Everything

Most people think boxing is just about physical strength. Honestly, it’s mostly about what’s happening in the head. And that morning, at the weigh-in, things got ugly.

While Griffith was standing on the scales in his socks and underwear, Paret leaned in. He didn't just talk trash. He leaned in and whispered "maricón" into Griffith's ear—a derogatory Spanish slur for a gay man. Then, he reportedly touched Griffith’s backside.

In 1962, that wasn't just an insult. It was a career-ender. It was a challenge to Griffith's very existence in the hyper-masculine world of professional sports. Griffith lunged at him right there at the New York State Athletic Commission offices. His trainer, Gil Clancy, had to physically restrain him. "Save it for tonight," Clancy told him.

✨ Don't miss: Celtic FC vs Bayern Munich: Why the Scoreboard Never Tells the Whole Story

Griffith did. He saved every ounce of that rage.

29 Punches in a Corner

The fight itself was a war. Paret actually almost finished Griffith in the sixth round. He caught him with a flurry that had the challenger reeling, but the bell saved him. By the 12th round, however, Paret was exhausted. His legs were heavy. He was a shell of the fighter who had entered the ring.

Then came the corner.

Griffith backed Paret into the turnbuckle and unleashed a barrage that defies description. Modern slow-motion analysis shows Griffith landed 29 unanswered punches in a matter of seconds. Paret’s head was trapped between Griffith’s gloves and the ring post. He had nowhere to go.

🔗 Read more: Hawaii at Utah State: Why This Mountain West Rivalry Still Matters

Norman Mailer was sitting ringside. He later wrote that Griffith’s right hand was "whipping like a piston rod which has broken through the crankcase." It wasn't just boxing anymore. It was a "pent-up whimpering sound" coming from Griffith as he swung.

The referee, Ruby Goldstein, seemed paralyzed. He stood there, watching the champion’s head bounce off the padding like a "pumpkin being demolished," as Mailer put it. By the time Goldstein finally stepped in, Paret was already gone. He didn't fall immediately; he slid down the ropes, his white satin trunks stained with blood. He never woke up. Ten days later, at the age of 25, Benny Paret died of brain injuries.

The Death of Boxing on TV

The fallout was immediate and massive. This wasn't some hidden tragedy; it happened on national television. People were horrified. You've got to understand, this was the moment the public's relationship with boxing shifted.

- The Political Firestorm: New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller launched an immediate investigation. There were legitimate calls in the State Legislature to ban boxing entirely.

- The Media Shift: ABC cancelled Fight of the Week shortly after. Live boxing on major networks basically went into a deep freeze for years.

- The Referee's Career: Ruby Goldstein, a veteran of over 500 fights, never refereed another match. The guilt of those few seconds of hesitation broke him.

What People Get Wrong About Griffith

There's this simplified narrative that Paret called Griffith a name, and Griffith killed him for it. It’s more complicated than that. Griffith was a man living in two worlds. By day, he designed women’s hats—he was actually a very talented milliner. By night, he was a world-class killer in the ring.

He wasn't "out" in the way we think of it today. He frequented gay bars in Times Square, but he also married a woman later in life. In a 2005 interview with Sports Illustrated, he gave one of the most famous quotes in sports history:

"I kill a man and most people understand and forgive me. However, I love a man, and many say this makes me an evil person."

After the Paret fight, Griffith was never the same. He fought for 15 more years because he didn't know how to do anything else, but the "killer instinct" was gone. He became a defensive specialist. He did just enough to win on points. He admitted he was terrified of hurting anyone ever again.

👉 See also: Why the Binghamton University Events Center is the Real Heart of the Southern Tier

The Long Shadow of the Ring

In his later years, Griffith suffered from "dementia pugilistica," a result of the 339 championship rounds he fought—more than Muhammad Ali. He lived a quiet life in New York, often seen at boxing events where he was treated like a ghost from a different era.

One of the most moving moments in sports history occurred decades later, captured in the documentary Ring of Fire. Griffith met Benny Paret’s son, Benny Jr. The younger Paret didn't come for revenge. He came to offer forgiveness. They embraced, two men tied together by a few seconds of violence that happened before one was even born.

Actionable Insights for Boxing Fans and Historians

To truly understand the legacy of Benny Paret and Emile Griffith, you have to look beyond the tragedy. It changed how we view athlete safety and the psychological toll of the sport.

- Watch the Documentary: If you want to see the human side, find Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story. It moves past the "slur" headline and looks at the men involved.

- Study the Refereeing: If you are a fan of combat sports, the 12th round of this fight is a masterclass in why "early stoppages" are often a mercy. Goldstein’s hesitation is still taught as a cautionary tale for modern officials.

- Acknowledge the Complexity: Don't buy into the "revenge" narrative. Paret had been brutally knocked out in several fights leading up to the Griffith match. His brain was likely already compromised before he even stepped into the ring that Saturday night.

The story of Griffith and Paret isn't a simple morality play. It’s a messy, tragic intersection of homophobia, sports culture, and the brutal reality of what happens when the human body is pushed too far.

To delve deeper into the history of the sport during this era, researching the career of Gil Clancy or the works of Norman Mailer provides a broader context of the 1960s boxing landscape.