You’ve probably heard it a thousand times during that groggy weekend in March. Someone, usually a well-meaning uncle or a trivia-obsessed friend, leans over their coffee and says, "You know, we can blame Benjamin Franklin for daylight savings time." It’s one of those historical "facts" that has been repeated so often it’s basically become gospel. People picture Franklin, the practical polymath, sitting in a candlelit room in Philadelphia, plotting a way to squeeze every bit of productivity out of the sun.

He didn't.

Seriously. The connection between Benjamin Franklin and daylight savings time is one of the most successful pranks in history. Franklin was a genius, a diplomat, and a scientist, sure. But he was also a world-class troll. If you actually look at the source material—a specific essay he wrote while living in France—it becomes pretty obvious that he wasn't proposing a legislative change to our clocks. He was making fun of the French for being lazy.

The Letter That Started the Myth

In 1784, Franklin was serving as the American envoy to France. He was 78 years old, suffering from gout, and living in the Parisian suburb of Passy. One morning, he was woken up at 6:00 AM by a loud noise. To his "great surprise," he found his room flooded with light.

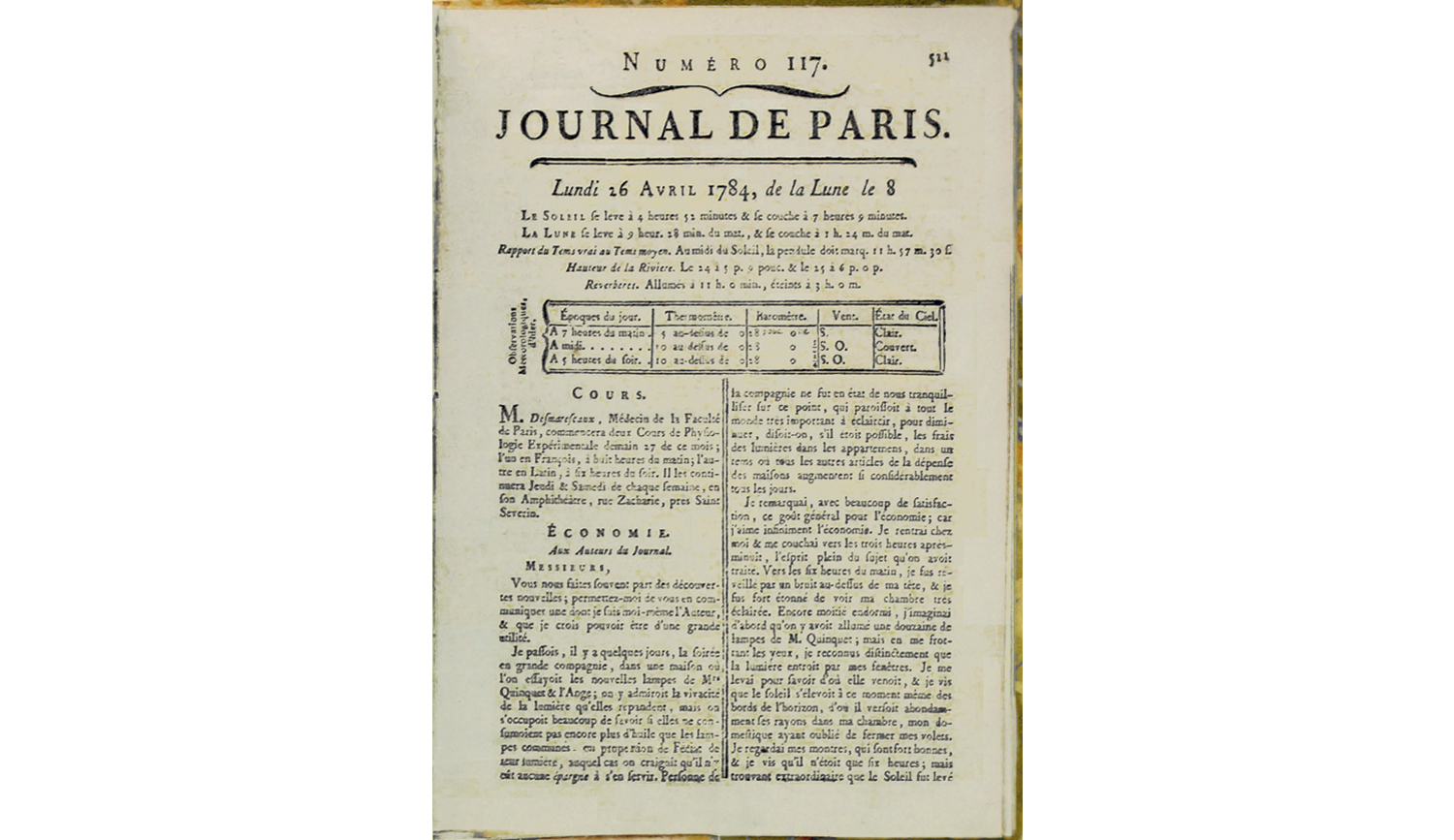

He wrote an anonymous letter to the Journal de Paris titled "An Economical Project." In it, he claimed he had made a miraculous discovery: the sun actually provides light as soon as it rises.

It’s hilarious if you read it with the right tone. Franklin adopts the persona of a shocked miser who can't believe he's been wasting money on candles by sleeping through the morning and staying up late at night. He calculates—with suspicious precision—that if 100,000 Parisian families burned half a pound of candles per hour between the hours of seven and midnight, they were wasting about 96 million French livres every year.

He didn't stop at math. To "solve" this problem, he suggested some pretty wild things. He proposed taxing shutters that blocked the sunlight. He suggested putting guards on the streets to stop people from using carriages after sunset. Most famously, he recommended firing cannons in every street at sunrise to "wake the sluggards effectively, and make them open their eyes to their true interest."

That’s not a policy proposal. That's a satire. He wasn't telling people to turn their clocks forward; he was telling them to get out of bed.

If Not Franklin, Then Who?

So, if the link between Benjamin Franklin and daylight savings time is mostly a joke, who actually gave us this system? We have to fast-forward about a century after Franklin's death to find the real "culprits."

The first person to seriously propose shifting the clocks was George Hudson, an entomologist in New Zealand. This was in 1895. Hudson didn't care about "saving" daylight for the masses; he just wanted more sunlight after work to collect bugs. He proposed a two-hour shift. People thought he was crazy.

A few years later, a British builder named William Willett—who, fun fact, is the great-great-grandfather of Coldplay’s Chris Martin—started a massive campaign for "Summer Time." He was an avid golfer and was annoyed that his rounds were getting cut short by the dusk. He spent a fortune lobbying the British Parliament, but he died in 1915 without ever seeing it happen.

The real catalyst wasn't bug collecting or golf. It was war.

Germany and Austria-Hungary were the first to actually implement Daylight Saving Time (DST) in 1916. Why? To conserve coal during World War I. If people were using the sun for light, they weren't burning fuel for lamps. The UK followed suit a few weeks later, and the United States finally jumped on board in 1918.

Why the Franklin Myth Won't Die

We love a good origin story. Linking Benjamin Franklin and daylight savings time feels right because it fits our image of him as the "Early to bed, early to rise" guy. It aligns with his reputation for thrift and practicality.

But there’s a massive technical difference between what Franklin wrote and what we do. DST is about shifting the clocks so that the sun sets later in the evening according to the time on our wrist. Franklin’s satirical essay was about shifting human behavior to match the sun's natural cycle. He never once suggested that 6:00 AM should suddenly be called 7:00 AM.

Honestly, he probably would have found the modern system unnecessarily complicated.

📖 Related: Top 10 Brands of Refrigerator: Why Popularity Doesn't Always Mean Reliability

There’s also the fact that DST wasn't even possible in Franklin's era. Time wasn't standardized. Every town had its own local time based on high noon. If you traveled from Philadelphia to New York, you had to reset your watch. It wasn't until the railroads came along in the mid-to-late 1800s that we needed a synchronized clock system. Without synchronized clocks, "saving time" by shifting an hour doesn't even make sense.

The Modern Reality of DST

Today, the debate over DST is more heated than ever. While Franklin's concern was the cost of tallow candles, our modern concerns are much more complex. We look at energy consumption, sure, but we also look at public health.

The data is kinda grim. Studies published in journals like the New England Journal of Medicine have shown a spike in heart attacks on the Monday after we "spring forward." Why? Because losing an hour of sleep wreaks havoc on the human body. It messes with our circadian rhythms, leads to more traffic accidents, and even causes a dip in workplace productivity (the "cyberloafing" effect).

Economically, the benefits are also debatable. While it might help retail and golf courses—people like to shop and play when it's light out—it doesn't actually save that much energy anymore. We have air conditioning now. If people are home for an extra hour of daylight, they're often running the AC, which uses way more power than a few LED lightbulbs.

Moving Past the Satire

If we want to be intellectually honest about history, we have to stop treating Franklin's 1784 letter as a blueprint. It was a masterpiece of 18th-century snark. He was poking fun at the "luxury and vice" of Paris, a city that stayed up late and slept through the morning.

When you hear someone bring up Benjamin Franklin and daylight savings time this year, you’ve got the real story. He wasn't the father of the clock-change; he was just a guy who was annoyed by loud noises in the morning and wanted his neighbors to wake up.

How to Actually Adjust to the Time Change

Since we’re stuck with the system for now (unless you live in Arizona or Hawaii), here is how to handle the shift without feeling like a zombie:

💡 You might also like: Questions To Ask A Friend When Bored: Why Most People Ask The Wrong Things

- Gradual Adjustment: Three days before the change, start going to bed 15 minutes earlier each night. It sounds like a hassle, but your internal clock will thank you.

- Seek Morning Sun: On the Sunday of the change, get outside as soon as the sun is up. Natural light is the strongest signal for your brain to reset its rhythm.

- Watch the Caffeine: It’s tempting to double down on espresso that first Monday morning. Don't. It just delays the "sleep debt" and makes Tuesday even worse.

- Audit Your Lighting: Use the time change as a reminder to check your home's efficiency. Franklin was right about one thing: wasting resources is silly. Swap out any remaining old-school bulbs for LEDs.

- Advocate for Change: If you're tired of the "spring forward," look into the Sunshine Protection Act. Several states have already passed legislation to stay on Permanent Daylight Saving Time, but it requires a change in federal law to take effect.

The history of Benjamin Franklin and daylight savings time is a reminder that some of our most deeply held beliefs are built on a foundation of satire. We should probably spend less time arguing over who "invented" the hour and more time making sure our current systems actually serve our health and well-being. Franklin, the man who valued "reason" above all else, would likely agree. He'd probably also suggest we stop firing cannons in the street.

Probably.