Walk down 44th Street in Manhattan and you’ll see the Belasco Theatre. It looks like a standard, albeit beautiful, piece of neo-Georgian architecture. But there is a literal world hidden below at the Belasco that most theatergoers never even think about while they’re munching on overpriced concessions.

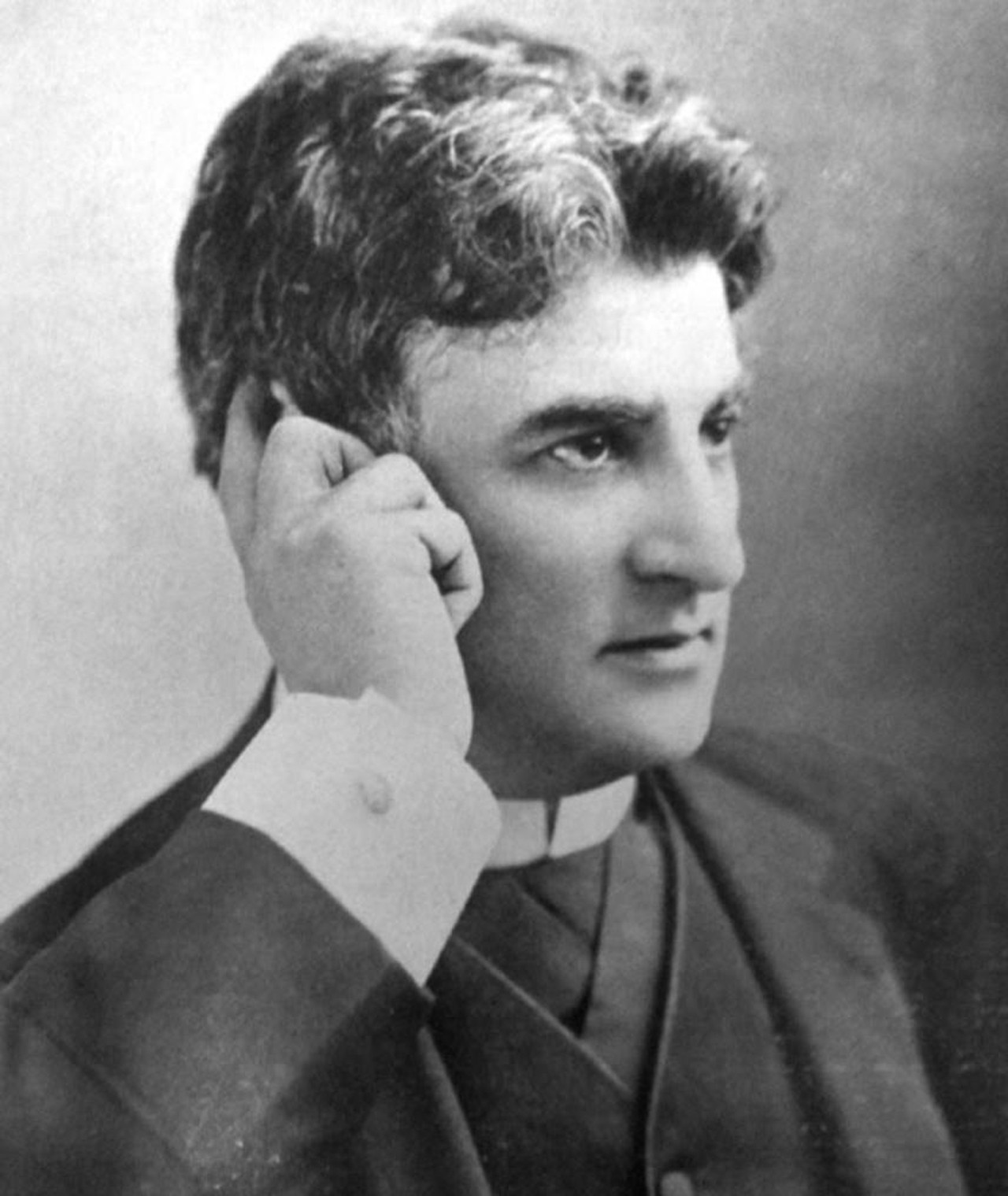

David Belasco was a weird guy. He was known as the "Bishop of Broadway" because he insisted on wearing a clerical collar, even though he wasn't a priest. He lived in a sprawling, multi-level penthouse right above the stage. However, the real soul of the building—and the source of nearly a century of urban legends—is tucked away in the basement and the sub-levels. This isn't just about storage or dressing rooms. It’s about a man who wanted to control every single molecule of atmosphere in his building.

What’s Actually Hiding Beneath the Floorboards?

Most people assume the space below a Broadway stage is just a dark hole for hydraulic lifts. At the Belasco, it was a laboratory. Belasco was obsessed with realism. He didn't want painted sunsets; he wanted light that mimicked the actual refraction of the sun. To do this, he built massive, cutting-edge electrical rooms and workshops below at the Belasco that were light years ahead of his time.

He was one of the first to ditch footlights. Think about that. Before him, actors were lit from the floor like spooky campfire stories. He moved the lights to the front of the balcony and used the basement to house the massive, humming machinery required to power his "secret" lighting effects.

It was loud. It was hot. It was dangerous.

The basement also housed his personal armory and a massive collection of "stuff." Belasco was a hoarder of the highest order. He collected Napoleonic relics, exotic silks, and antique furniture. When he produced a play, he didn't use props. He used the real thing. If a scene called for a 17th-century French rug, he’d pull one out of his subterranean stash.

The Ghostly Elephant in the Room

You can't talk about this place without talking about the ghosts. Honestly, if you ask any stagehand who has worked a long run there, they’ll have a story. The most famous is, of course, the Bishop himself. People see him in the balcony, sure, but the "cold spots" and the feeling of being watched are most intense in the passageways below at the Belasco.

💡 You might also like: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

There's a specific elevator—or where the elevator used to be—that connects the basement to the penthouse. Legend has it that the ghost of a "Blue Lady" wanders the lower levels. Some say she was a showgirl; others say she was an office worker who fell down the elevator shaft in the early 1900s. Whether you believe in the supernatural or just think old buildings have weird drafts, the basement of the Belasco is undeniably heavy. It feels like the air is thicker down there.

The 2010 Renovation: Uncovering the Past

When the Shubert Organization dumped $14.5 million into a massive restoration around 2010, they had to dig deep. They weren't just slapping on a coat of paint. They were trying to restore the theater to its 1907 glory. This meant dealing with the infrastructure below at the Belasco that hadn't been touched in decades.

They found original Tiffany lighting fixtures. They found intricate woodwork that had been boarded over. They even restored the famous murals by Everett Shinn. But the most impressive part was how they modernized the basement while keeping the "bones" of Belasco's vision. They had to navigate a labyrinth of old brick and mortar to install modern HVAC systems without disturbing the theater’s legendary acoustics.

It’s a balancing act. You want the Wi-Fi to work, but you don't want to piss off the spirits of the guys who built the place with their bare hands.

Why the "Lower Level" Matters for Modern Productions

When a show like Network or Appropriate moves into the building, the space below at the Belasco becomes a hive of activity. Modern Broadway shows require an insane amount of tech. Cables, automation computers, and quick-change booths are squeezed into every available inch of the basement.

- The Trap Room: This is the area directly under the stage floor. If an actor "disappears" through a trapdoor, they are landing in a meticulously padded area in the basement.

- The Orchestra Pit: At the Belasco, the pit is intimate. The musicians are basically nestled into the edge of the basement structure.

- Dressing Rooms: While the stars get the nice rooms, the ensemble is often relegated to the lower levels. It's a rite of passage.

The basement is where the "magic" is deconstructed. Up on stage, everything is seamless. Below the stage, it's a chaotic mess of gaff tape, sweat, and frantic costume changes.

📖 Related: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

The Architectural Quirk Nobody Notices

Belasco was a pioneer of the "basement-to-ceiling" ventilation system. In an era when theaters were death traps of heat and stagnant air, he designed a way for air to circulate from the lower levels upward. It wasn't air conditioning—not yet—but it was a proto-version of climate control. He understood that if the audience was sweating, they weren't paying attention to the play.

This meant the basement had to be kept relatively clean and unobstructed. It’s one reason why the theater has survived so well. It was built with airflow in mind, preventing the kind of rot and mold that destroyed many other 44th Street venues.

Finding the Truth Behind the Myths

Is there a secret tunnel to the Algonquin Hotel? Probably not. People love to say there is, but New York City's bedrock and subway system make "secret tunnels" a logistical nightmare. However, there are walled-off sections. Over a century of renovations means that some doors lead to nowhere. Some staircases end in a brick wall.

That’s where the "spooky" reputation comes from. It’s not necessarily malevolence; it’s just the architectural scars of 120 years of show business.

When you're below at the Belasco, you’re standing in a place that has seen the rise and fall of vaudeville, the birth of modern lighting, and the transition from silent-era spectacles to the high-tech dramas of today. It is a time capsule with a very high ceiling.

How to Experience the Belasco History Yourself

You can't just wander into the basement. Security is tight, and it's a working Union house. But you can see the influence of the underground infrastructure if you know where to look.

👉 See also: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

- Check the Side Walls: Look at the intricate lighting coves. Those are powered by the massive electrical conduits that run through the basement floors.

- Feel the Air: Notice how the theater breathes. You’re feeling a modern version of David Belasco’s original ventilation experiments.

- The Stage Edge: If you’re in the front row, look at the gap between the stage and the pit. That’s the gateway to the "underworld" of the production.

- The Murals: The Shinn murals in the lobby and auditorium were all influenced by the "realist" movement Belasco fostered in his basement workshops.

The Belasco isn't just a building. It's a machine. The stage is the interface, but the engine is, and always has been, humming away in the dark spaces downstairs.

Actionable Insights for Theater Nerds

If you’re obsessed with theater history or just want to appreciate your next show more, keep these points in mind.

First, ignore the tourist traps. Don't pay for "ghost tours" that promise a sighting of the Bishop. Instead, read The Bishop of Broadway by Craig Timberlake. It’s the definitive source on how Belasco utilized his space.

Second, if you ever get the chance to take a backstage tour (usually through a charity auction or Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS), jump on it. Ask specifically to see the trap room. It’s the only way to truly understand the scale of the work happening below at the Belasco.

Finally, pay attention to the lighting during the next show you see there. That legacy of innovation started in a damp basement with a man who refused to follow the rules. It’s a reminder that great art usually requires a lot of heavy lifting in the dark.