You’re standing in the mud at 6:00 AM, staring at a three-ton rhinoceros with a suspicious-looking abscess on its flank. The sun isn't even fully up yet. Your coffee is cold. Most people think being a zoo vet is all about cuddling tiger cubs or bottle-feeding abandoned monkeys, but honestly, it’s mostly about logistics, spreadsheets, and trying not to get kicked into next week. It’s a weird life. One day you’re doing microscopic surgery on a tree frog’s leg, and the next you’re calling a construction firm because you need a crane to move an anesthetized giraffe.

It's loud. It's smelly. It’s incredibly rewarding, sure, but it’s also exhausting in a way that most desk jobs can't quite touch.

The Reality of Being a Zoo Vet vs. The Dream

Forget what you saw on those glossy nature documentaries. In those shows, everything is high-drama and cinematic lighting. In the real world, the "drama" is often figuring out why a tortoise hasn't had a bowel movement in three days. You spend a massive chunk of your time on preventative medicine. Think of it like being a pediatrician, but your patients can’t talk, and some of them could literally eat you if they were in a bad mood.

We do a lot of "wellness checks." That means fecal samples. Lots of them. If you’re squeamish about parasites, this isn't the career for you. We look for Strongyloides or Giardia under a microscope for hours because catching a parasitic load early saves lives.

It’s about the subtle stuff. Animals are masters at hiding pain. In the wild, showing weakness means you're lunch. So, by the time a snow leopard actually looks sick, it’s usually in serious trouble. You have to be a detective. You look at the way a bird is ruffling its feathers or whether a gorilla is sitting slightly differently than it was yesterday. It's high-stakes observation.

The Math and Physics of the Job

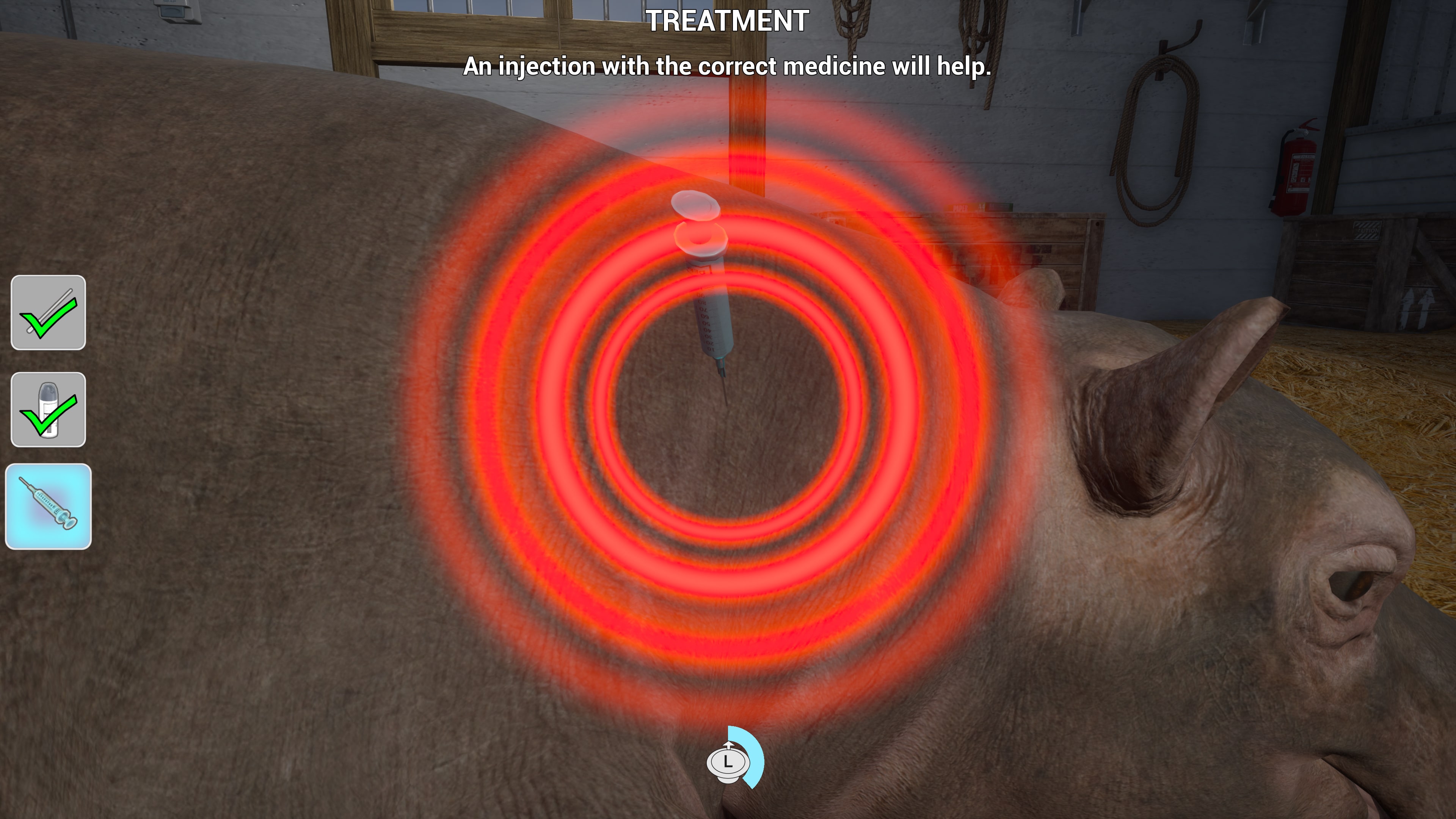

People forget how much engineering goes into this. When a lion needs a root canal, you don’t just walk in there. You have to calculate the exact dosage of Telazol or Medetomidine based on its estimated weight. Get it wrong? The animal wakes up too early, or worse, doesn't wake up at all.

There's no room for "kinda close" here.

You’re constantly collaborating with specialists too. We aren't just general practitioners; we’re also anesthesiologists, radiologists, and sometimes even nutritionists. You might consult with a human cardiologist because great apes have hearts remarkably similar to ours. The American Association of Zoo Veterinarians (AAZV) actually publishes massive amounts of research on this cross-species medicine. It's a small world. Everyone knows everyone.

📖 Related: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

Why the Career Path is Brutal

Let’s be real: getting into this field is a nightmare.

You need the four-year undergraduate degree. Then four years of vet school. Then, usually, a one-year internship in small or large animal medicine. After that, you're looking at a three-year residency specifically in zoological medicine.

Competition? It’s cutthroat. There are only a handful of residency spots in the entire U.S. each year.

- You’re competing against the smartest people you’ve ever met.

- The pay is... fine. But compared to a private practice vet who does orthopedics for Golden Retrievers in the suburbs? You’re making way less.

- The hours are unpredictable. Emergencies don't happen on a 9-to-5 schedule.

Basically, you do it because you can't imagine doing anything else. You do it for the conservation. You do it because you want to help preserve species like the Amur leopard or the California condor. If you're in it for the money or the "cool factor," you’ll burn out in twenty-four months.

What No One Tells You About the Gear

The equipment is basically a mix of high-tech medical tech and stuff you’d find at a Home Depot. We use $50,000 portable X-ray machines that can link to an iPad, which is amazing. But we also use PVC pipes to blow-dart animals or heavy-duty ratchet straps to secure a sedated zebra on a transport sled.

It's "MacGyver" medicine.

I remember once having to figure out how to nebulize a dolphin with a respiratory infection. You can’t exactly put a mask on a blowhole and expect it to stay there. You have to build custom hoods. You have to innovate on the fly. You're constantly looking at tools designed for humans or cows and figuring out how to make them work for a penguin.

👉 See also: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

The Emotional Toll of the "Zoo Vet" Life

There’s a thing called compassion fatigue. It’s real.

When you spend years working with a specific animal, you form a bond. Even if you try to keep a professional distance, you know their personality. You know that the older matriarch elephant likes to splash water on the keepers when she's bored. When her health starts to fail due to age-related arthritis or kidney issues, it’s heavy.

Euthanasia is the hardest part. Deciding when a "quality of life" has dipped too low for a majestic creature that represents an endangered species is a burden that stays with you. You have to balance the individual animal's welfare with the goals of the Species Survival Plan (SSP). It's a lot of pressure.

Misconceptions About Captivity

A lot of folks think zoos are just cages.

Modern, accredited zoos (look for the AZA or EAZA logos) are more like research stations and genetic arks. As a zoo vet, you’re a part of that mission. You’re collecting semen samples for artificial insemination to maintain genetic diversity. You’re treating injuries in animals that were rescued from the illegal wildlife trade.

You aren't just "keeping them in a cage." You're managing a population.

Sometimes we treat wild animals too. Many zoos have "rehab and release" programs. If a wild raptor is brought in with a broken wing, we fix it and get it back out there. That’s the stuff that doesn't get onto the brochures, but it's a huge part of the daily grind.

✨ Don't miss: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

The Science of Stress

Stress is the enemy.

Anesthetizing an animal is always a risk. The goal is to do as much as possible with "husbandry training." This is where the keepers are the real heroes. They spend months training a blood-draw-friendly tiger to lean against a fence and present its tail for a needle poke.

If we can do a physical exam while the animal is awake and relaxed, that’s a win.

It saves the animal the stress of a dart and the recovery from drugs. We use positive reinforcement—lots of treats. For a sea lion, it might be extra fish. For a primate, maybe some diluted juice or a piece of grape. It’s all about trust. If the animal trusts the keeper, my job as the vet becomes infinitely safer and more effective.

How to Actually Start Toward This Path

If you’re reading this and thinking, "Yeah, I still want to do that," then you need a plan.

- Volunteer now. Don't wait for vet school. Clean stalls. Prep diets. Learn how to read animal behavior by being around them.

- Focus on the "boring" sciences. Biochemistry and physiology are the foundations of everything we do.

- Get comfortable with public speaking. You will have to explain medical procedures to donors, the press, and the public. You’re an ambassador as much as a doctor.

The world of the zoo vet is shrinking and expanding at the same time. Climate change and habitat loss mean more animals are ending up in managed care. We need people who are brilliant, resilient, and willing to get covered in unidentifiable fluids for the sake of a species they might never see in the wild.

It’s not just a job. It’s a weird, difficult, beautiful way to live.

Actionable Next Steps

- Check Accreditation: If you want to support or work in this field, only look at institutions accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA). They hold the highest standards for animal welfare and veterinary care.

- Shadow a Local Vet: Most zoo vets start in "regular" clinics. Find a local exotic animal vet and ask to shadow for a day to see if you can handle the non-traditional patients.

- Read the Journals: Look up the Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. It’ll give you a real taste of the complex cases we actually deal with, from fungal infections in snakes to heart disease in gorillas.

- Focus on Comparative Anatomy: Start studying how different species are built. Understanding the skeletal differences between a bird, a reptile, and a mammal is the first step toward being able to treat them all.