It sounds cool, doesn't it? Behind the enemy lines. You probably picture a lone wolf like Chris Huget or a Navy SEAL team moving with surgical precision through a dark forest, suppressed rifles at the ready, and a perfect extraction plan waiting at the extraction point.

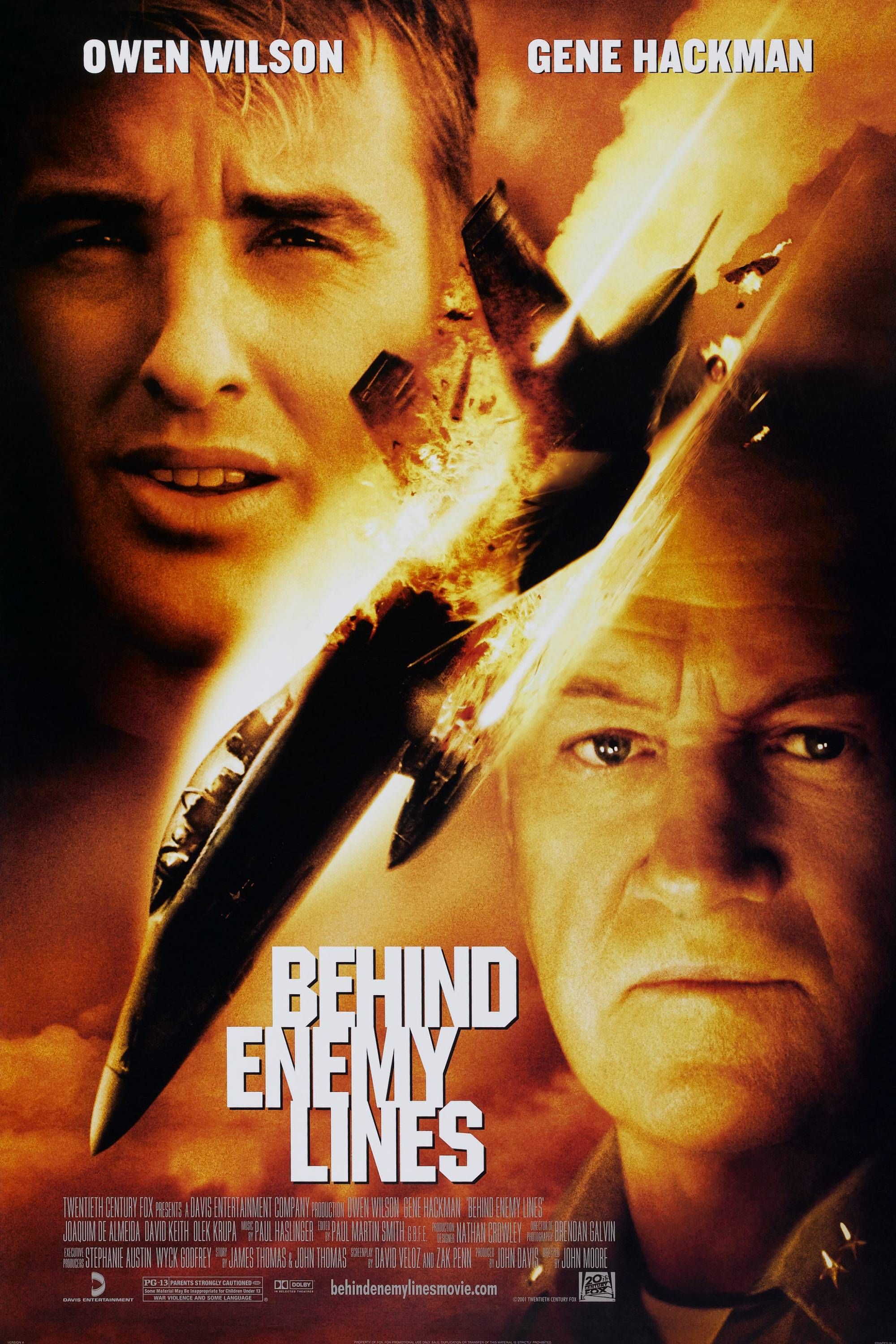

Hollywood loves this.

The reality is usually a lot more "sitting in a hole for four days eating cold mush" and "trying not to sneeze because your life depends on it."

Operating behind enemy lines—often referred to in military doctrine as Deep Operations or Unconventional Warfare—is less about the shooting and more about the waiting. It’s a psychological grind. You aren't just fighting an army. You're fighting the terrain, the weather, and your own nervous system.

The Brutal Physics of Survival

When a small unit crosses the Forward Line of Own Troops (FLOT), they enter a world where the math is immediately stacked against them.

Think about it.

If you get a toothache, there is no dentist. If you run out of water, you’re looking for a puddle and praying your purification tablets work. If you get shot, your buddies have to carry you, which means the whole team slows down to a crawl. This isn't just "toughing it out." It is a logistical nightmare.

Historically, we've seen this play out in places like the Ardennes during World War II or the triple-canopy jungles of Vietnam. The Long Range Reconnaissance Patrols (LRRPs) in Vietnam are probably the best example of what this actually looks like. These guys would go out in six-man teams. They weren't looking for a fight. Honestly, if they had to fire their weapons, something had gone horribly wrong.

Their job was to be ghosts.

They watched trail intersections. They counted trucks. They listened. Sometimes they just sat still for 48 hours straight. Imagine that. You can't talk. You can't smoke. You can't even move too much because the rustle of nylon or a clicking buckle can carry for hundreds of yards in a quiet jungle.

Why the "Lone Survivor" Trope is Mostly Wrong

Marcus Luttrell’s story from Operation Red Wings is famous, but it’s an outlier for a reason. Most successful missions behind the enemy lines end with the team coming home without ever having pulled a trigger.

In modern warfare, specifically what we’re seeing in Eastern Europe right now, being "behind lines" has changed. Drones are everywhere. Thermal imaging is cheap. In the 1990s, you could hide in a thicket. In 2026, a $500 quadcopter with a heat-sensing camera will spot your body heat through the leaves in seconds.

👉 See also: Margaret Thatcher Explained: Why the Iron Lady Still Divides Us Today

The "lines" aren't even lines anymore. They’re porous, shifting zones.

The Mental Game of Deep Penetration Missions

Let's talk about the brain.

When you are in "friendly" territory, your brain has a baseline level of safety. Behind the enemy lines, that baseline is zero. Every sound is a threat. A snapping twig? Could be a deer. Could be a local farmer. Could be a Spetsnaz patrol.

Expert operators, like those from the British SAS or US Army Special Forces, talk about "situational awareness fatigue." You can only stay at peak alertness for so long before your brain starts to misinterpret signals. You start seeing shadows that move. You become hyper-irritable.

Resistance and Local Support

You can't do this alone for long.

The most successful instances of operating behind enemy lines involve the "Human Domain." This is a fancy military term for making friends with the locals. During WWII, the French Resistance (Maquis) provided the "eyes and ears" for Allied Jedburgh teams.

Without the local population, an operator is just a target. With them, they are an invisible force.

But this is risky. Who do you trust? In the Syrian conflict, special operations teams had to navigate a dizzying array of local militias. One village might be friendly; the next might sell you out for a bag of flour or out of fear of retaliation. It’s a high-stakes game of social engineering.

Modern Tech vs. Old School Stealth

Technology has made being behind the enemy lines both easier and infinitely more dangerous.

On one hand, we have:

- Burst Transmissions: Gone are the days of long radio calls that can be easily triangulated. Now, you can send a massive encrypted file in a fraction of a second.

- Satellite Imagery: Teams know the terrain before they even hit the ground.

- High-Calorie Low-Weight Rations: You can carry more energy for less weight.

But the enemy has toys too.

✨ Don't miss: Map of the election 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

Signal intelligence (SIGINT) is the biggest killer. If you turn on a radio or a GPS device, you are emitting a signature. In a "clean" environment where there shouldn't be any electronic signals, you stick out like a flare in a dark room. Electronic Warfare (EW) units can pin your location within meters just by catching a stray ping from a cell phone or a tactical radio.

This is why "low-tech" is making a comeback.

Some units are going back to using signal mirrors, hand signals, and even messenger pigeons in extreme testing environments because you can't "hack" a bird or "jam" a mirror.

The High Cost of Discovery

What happens when you’re caught?

It’s not like the movies where you have an infinite ammo belt and a cinematic escape. Usually, you’re surrounded. The ratio is typically 100 to 1.

Take the Bravo Two Zero mission during the Gulf War. A British SAS patrol was inserted deep into Iraq to find Scud missiles. They were spotted by a young goat herder. Within hours, they were being hunted by mechanized infantry. They had to run across miles of open desert in freezing conditions. Some died of hypothermia; others were captured and tortured.

There’s no "reset" button.

The Legal Grey Zone

If you are a soldier in uniform behind the enemy lines, you are (theoretically) protected by the Geneva Convention as a Prisoner of War.

But what if you’re in civilian clothes?

Now you’re a spy or a "saboteur." You lose those protections. This is the world of the CIA’s Ground Branch or various "black ops" units. They operate in a space where their government will deny they even exist if they get caught. That is a level of pressure most people can't even fathom.

How Military Reconnaissance Actually Works

Most people think recon is about looking at things. It’s actually about reporting things accurately.

🔗 Read more: King Five Breaking News: What You Missed in Seattle This Week

If a scout team sees a tank, that’s okay. If they can report the tank's hull number, the direction it’s facing, the amount of mud on its treads (indicating how far it’s traveled), and whether the crew looks tired—that is gold.

- Infiltration: Usually via HAHO (High Altitude High Opening) parachute or sub-surface swimming.

- The LUP (Lying Up Point): Finding a spot to hide that is so miserable no one else would ever go there. Think swamps or briar patches.

- Observation: Rotating sleep cycles. One person watches, one person sleeps, one person handles comms.

- Exfiltration: Getting out is often harder than getting in. You’re tired, you’re out of food, and the enemy knows you’re there now.

Misconceptions We Need to Kill

Myth 1: You need to be a giant bodybuilder. Nope. Giant muscles require a lot of calories and a lot of oxygen. The best operators are often "wiry." They look like marathon runners. They can carry a 90-pound pack for 20 miles and not collapse.

Myth 2: It’s all about the gear. Gear breaks. Batteries die. The most important tool is a map and the ability to read it. If your GPS fails in the middle of a forest in a foreign country, do you know how to find north using the stars? If not, you’re dead.

Myth 3: Silence is easy. Have you ever tried to be silent in the woods? Everything makes noise. Your knees pop. Your clothes swish. The velcro on your pocket sounds like a gunshot.

Lessons for the Average Person

You probably aren't going to be dropped behind the enemy lines anytime soon. (At least, I hope not.) But the principles of these missions apply to high-stakes life situations.

- Preparation is everything. You don't "rise to the occasion." You sink to the level of your training.

- Information is more valuable than force. Knowing what’s coming is always better than reacting to it.

- Redundancy saves lives. If you have one of something, you have none. If you have two, you have one.

Actionable Steps for Deep Understanding

If you want to actually understand this world beyond the fluff, stop watching action movies and start looking at primary sources.

Read the AARs (After Action Reports). The US military and other organizations often declassify mission summaries after a few decades. Look for reports from the MACV-SOG era or early ODA missions in Afghanistan. You’ll see the "unfiltered" version of mistakes, gear failures, and the sheer boredom of the job.

Study Human Geography. Understand why people in certain regions act the way they do. If you are interested in the "behind the lines" aspect of warfare, you need to understand culture more than ballistics.

Practice Low-Signature Living. This is a fun exercise. Go for a hike and try to see how close you can get to a trail without being noticed by other hikers. You’ll quickly realize how loud your breathing is and how bright your "tactical" gear actually looks in a natural setting.

Master Land Navigation. Buy a topographic map of a local state park and a baseplate compass. Learn how to "dead reckon." It’s a perishable skill and it’s the foundation of every mission behind the enemy lines.

The reality of operating in hostile territory is a mix of extreme patience and sudden, violent chaos. It is not for the faint of heart, and it certainly isn't what you see on the big screen. It’s a quiet, lonely, and terrifying business that relies on the strength of the human spirit more than the tech in a soldier's hands.