Beethoven was only twenty-seven when he changed piano music forever. It’s kinda wild to think about. At an age when most of us are still figuring out how to file taxes or keep a houseplant alive, Ludwig van Beethoven was busy shattering the polite, tinkling conventions of the late 18th century. He wrote Piano Sonata No. 8 in C minor, Op. 13, and the world basically didn't know what hit it.

Most people call it the Pathétique Sonata.

That wasn't actually his idea, by the way. His publisher, Joseph Eder, came up with the name "Grande sonate pathétique" because the music felt so thick with tragic, soulful energy. Beethoven didn't object, though. He knew he’d captured something raw. This wasn't background music for a royal dinner party. It was a scream.

The C Minor Obsession

If you look at Beethoven’s career, C minor is where he kept his demons.

Whenever he wrote in this key, things got dark. Think about the Fifth Symphony. You know the one—da-da-da-dum. That’s C minor. The Pathétique Sonata uses that same key to create a sense of impending doom right from the first chord. Most sonatas of that era started with a snappy, cheerful melody. Beethoven? He starts with a massive, crashing C minor chord marked Grave. It’s heavy. It’s slow. It feels like you're walking through mud in a thunderstorm.

Then, suddenly, he shifts.

The music starts racing. The Allegro di molto e con brio section takes off like a shot. Honestly, if you’re a pianist, this part is a nightmare for your left hand. You have to play these "murky basses"—rapidly oscillating octaves—that make your forearm feel like it's on fire after about thirty seconds. This contrast between the slow, crushing intro and the frantic main theme is what makes the Piano Sonata No. 8 feel so modern. It’s moody. It’s bipolar. It’s exactly how a brilliant, frustrated young man in Vienna would feel while realizing he was starting to lose his hearing.

Breaking the Rules of the 1790s

Haydn and Mozart were the kings before Beethoven. They liked balance. They liked symmetry. If they wrote a sonata, you generally knew where the "surprise" was going to be.

Beethoven decided to ignore the manual.

📖 Related: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

In the first movement of the Pathétique Sonata, he does something weird: he brings back the slow, tragic Grave section in the middle of the fast movement. And then he does it again at the very end. This was a huge "no-no" in traditional sonata form. It’s like a movie that keeps cutting back to a flashback just when the action gets good. But it works because it keeps the listener off-balance. You’re never quite safe.

That Second Movement (The One You’ve Heard Before)

Even if you think you don't know classical music, you know the second movement of the Pathétique Sonata.

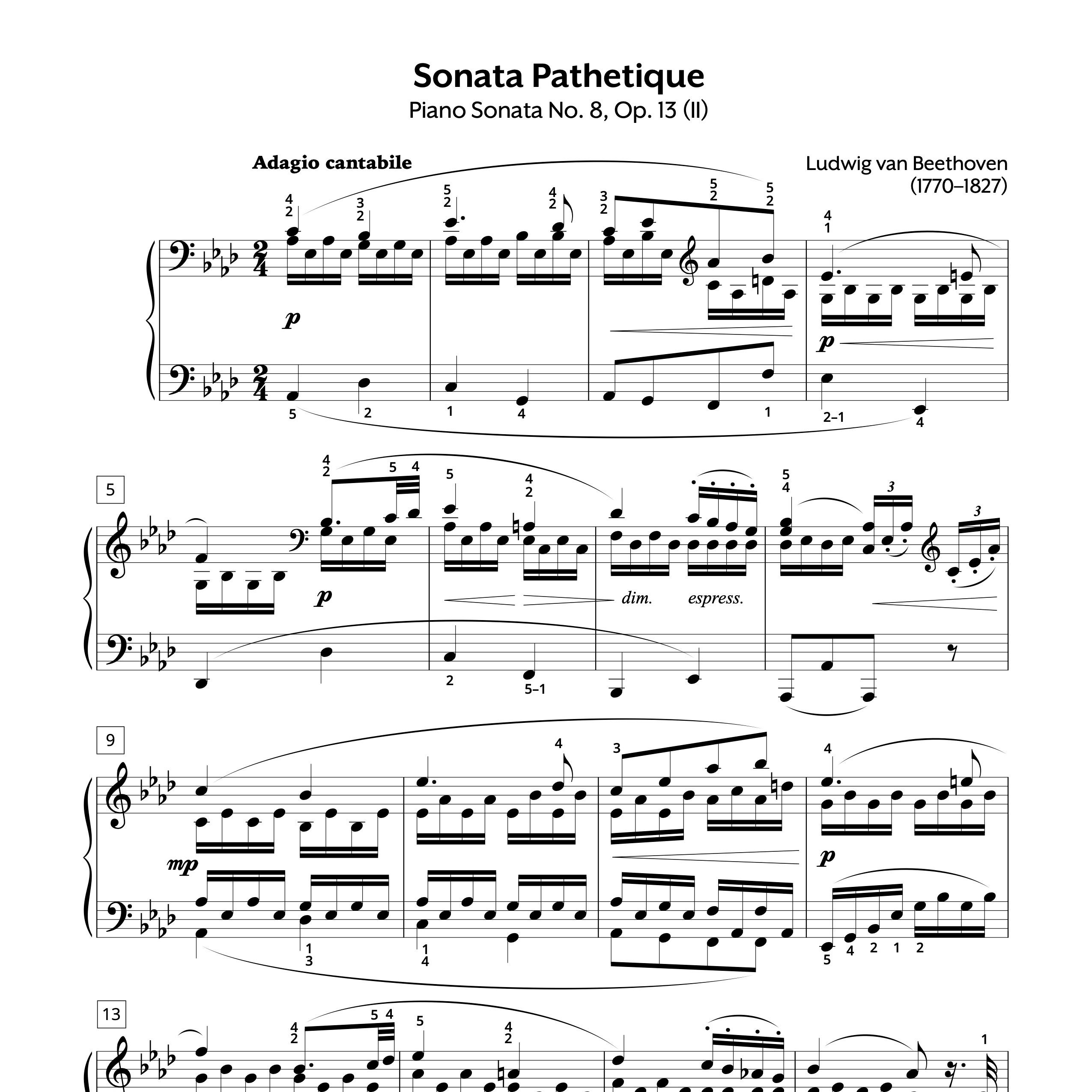

It’s the Adagio cantabile.

It’s been sampled by everyone from Billy Joel (in "This Night") to KISS. It’s the kind of melody that feels like it has always existed. It’s simple, soulful, and honestly, a bit heartbreaking. While the first movement is all about fire and fury, the second movement is pure comfort.

- The Melody: It stays in the middle of the keyboard, mimicking a human singing.

- The Atmosphere: It’s written in A-flat major, which is a warm, "thick" key.

- The Contrast: It provides a necessary breath of air between the chaos of the first and third movements.

But don't let the beauty fool you. Underneath that gorgeous melody is a pulsing accompaniment that never stops. It’s like a heartbeat. Beethoven keeps the tension alive even when he’s being "nice" to his audience.

The Finale: Not Your Average Rondo

By the time you get to the third movement, the Rondo, you’d expect a big, triumphant finish. That was the standard. Mozart usually ended things with a smile.

But Beethoven keeps the Pathétique Sonata in C minor until the very last note.

The Rondo theme is actually derived from the second theme of the first movement. It’s a bit of "thematic transformation" that nerdier musicologists like Charles Rosen love to point out. It makes the whole sonata feel like one long, coherent thought rather than three random songs stuck together. It’s leaner than the first movement, but there’s a nervous energy to it. It’s like someone trying to act calm while their heart is still racing from a fight.

👉 See also: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

The Technical Hurdle

If you’re thinking about learning this piece, be warned. It’s often the first "big" sonata a piano student tackles, but it’s a trap.

The difficulty isn't just in the fast notes. It's in the voicing. In the second movement, you have to play the melody, the bass line, and the middle accompaniment all with just two hands, making the melody stand out like a solo singer. It requires a level of finger independence that most people spend years perfecting.

And that first movement? The hand-crossing section in the second theme is a classic "show-off" move. You have to cross your right hand over your left to hit these low, biting notes while the left hand keeps jumping around. It looks cool in concert, but it’s incredibly easy to miss if you aren't looking.

Why We’re Still Talking About Op. 13 in 2026

It’s about the "Sturm und Drang."

That’s a German phrase meaning "Storm and Stress." Before the Pathétique Sonata, music was often about elegance. After this sonata, music became about emotion. Beethoven proved that a solo piano could sound like a full orchestra. He pushed the physical limits of the pianos of his time—which, frankly, were kind of wimpy compared to a modern Steinway. He was literally breaking strings and snapping hammers because he wanted more sound than the technology could give him.

When you listen to Piano Sonata No. 8, you're hearing a man at war with his instrument and his era.

There’s also the tragedy of his life. Around 1798, when he was writing this, Beethoven was starting to notice a ringing in his ears. Tinnitus. He was terrified. He was the most famous virtuoso in Vienna, and he was going deaf. That desperation is baked into the DNA of the Pathétique. It’s not just a "sad" song. It’s a fight for survival.

Common Misconceptions About the Pathétique

A lot of people think the "Pathétique" subtitle implies weakness or "pathetic" in the modern sense.

✨ Don't miss: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

Actually, in the 18th century, pathétique meant "passionate" or "full of pathos." It was about evoking a strong emotional response. It’s a "Pathetic" sonata in the way a Greek tragedy is pathetic—it moves you to pity and fear.

Another myth is that Beethoven was the first to use this style. He wasn't. He was heavily influenced by Jan Ladislav Dussek and Muzio Clementi. If you listen to Dussek’s "The Sufferings of the Queen of France," you can hear some of the same dramatic tricks. But Beethoven took those tricks and turned them into high art. He had a way of taking a simple three-note motif and beating it into your brain until you couldn't forget it.

How to Actually Listen to the Pathétique Sonata

If you want to get the most out of this piece, don't just put it on as study music. It’s too distracting for that.

- Find a "Period" Recording: Listen to someone like Brautigam play it on a fortepiano. It sounds thinner, more metallic, and much more violent. You can hear the instrument struggling to keep up with Beethoven’s demands.

- Watch the Left Hand: If you're watching a video, pay attention to the tremolos in the first movement. It looks like the pianist’s hand is vibrating. That’s the "murky bass" mentioned earlier.

- The Silent Gaps: Notice the silences in the Grave sections. Beethoven uses silence as a weapon. The gaps between the loud chords are just as important as the notes themselves.

- Compare Interpretations: Listen to Glenn Gould’s version (which is weirdly fast and controversial) and then listen to Emil Gilels or Daniel Barenboim. It’s the same notes, but it feels like a completely different story.

The Piano Sonata No. 8 isn't just a museum piece. It’s a blueprint for the Romantic era. Without the Pathétique, you don't get Chopin. You don't get Liszt. You don't get the big, emotional movie scores we love today. It was the moment music stopped being polite and started being real.

To truly master or even just appreciate this work, one should look at the score while listening. Even if you don't read music, you can see the "blackness" of the page in the fast sections—how dense the notes are. That visual density translates directly to the physical energy required to play it. It’s an athletic feat as much as an artistic one.

Next time you're feeling overwhelmed or just need to hear someone else express a bit of "storm and stress," put on the Pathétique. It’s been helping people process their emotions for over 220 years, and it's not slowing down anytime soon.

Practical Steps for Music Lovers:

- Listen to the "Heiligenstadt Testament": Read this letter Beethoven wrote a few years after the Pathétique. it explains his mental state and his hearing loss, which provides massive context for the "tragedy" in his music.

- Trace the Influence: Listen to Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 14 in C minor. You’ll hear exactly where Beethoven got his inspiration, and you’ll see how much further he pushed the boundaries.

- Check the Tempo: If you’re a student, use a metronome on the Allegro section. The biggest mistake people make is rushing the "easy" parts and slowing down for the "hard" parts. Consistency is what makes this piece sound professional.