You’re sitting on your porch in Mid City, watching the sky turn that weird, bruised shade of purple-green that only happens in South Louisiana. You check your phone. The little sun icon says it’s clear. But you can smell the ozone. You know better. The reality is that "Baton Rouge doppler weather radar" isn't just one thing you see on a screen; it’s a complex, aging, and incredibly sophisticated network of pulses that keep us from getting blindsided by a random June microburst.

Weather in the 225 is temperamental. It’s moody. One minute you’re sweating through your shirt at a tailgate, and the next, a wall of water is turning Nicholson Drive into a literal river. Relying on a generic weather app that aggregates data from three states away is a recipe for a ruined weekend—or worse.

The Big Dog: KLCH vs. KLIX

Most people don't realize that Baton Rouge is actually in a bit of a "radar hole." We don't have our own dedicated NEXRAD (Next-Generation Radar) tower sitting right in the middle of downtown. Instead, we’re caught in the crosshairs of several surrounding stations.

💡 You might also like: Space Grey MacBook Pro: Why the Color Choice Actually Matters

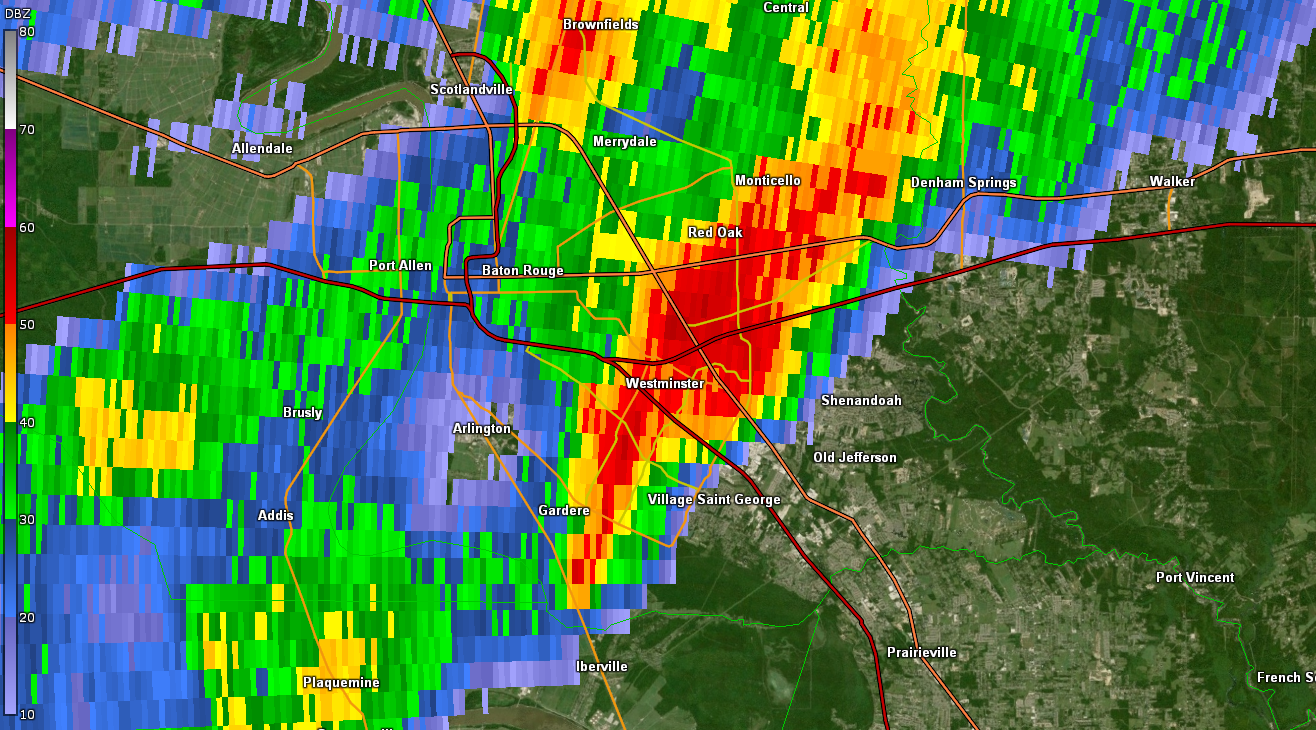

The most important one for us is usually KLIX, located in Slidell. This is the National Weather Service (NWS) New Orleans/Baton Rouge station. When you see those big colorful blobs moving across your screen, that’s often the pulse coming out of Slidell. However, if the weather is screaming in from the west—which it usually does during the spring—you’re actually looking at data from KLCH in Lake Charles.

Why does this matter? Physics.

Because the Earth is curved (sorry, flat-earthers), the further the radar beam travels from the tower, the higher up in the atmosphere it goes. By the time the beam from Slidell reaches Baton Rouge, it’s scanning thousands of feet above the ground. It might see a massive thunderstorm brewing at 10,000 feet, but it might miss the smaller, lower-level rotation that could drop a "spin-up" tornado in a neighborhood in Zachary or Central. This is the "beam overshoot" problem. It’s why local meteorologists like Jay Grymes or the team at WBRZ often supplement official NWS data with their own smaller, "gap-filler" radars.

How the Magic (Physics) Actually Works

Doppler radar isn't just a camera. It’s more like a bat’s ears. It sends out a microwave pulse. That pulse hits something—a raindrop, a hailstone, or even a swarm of dragonflies—and bounces back.

But the "Doppler" part is the secret sauce. Just like a siren sounds higher-pitched as it moves toward you and lower as it moves away, the frequency of the radar pulse changes depending on whether the rain is moving toward the radar tower or away from it.

This is how we see wind.

If a meteorologist sees bright green (moving toward) right next to bright red (moving away), their heart rate spikes. That’s a couplet. That’s rotation. That’s a tornado. In Baton Rouge, where the trees are heavy and the visibility is low, this data is literally the only thing that gives you a ten-minute head start to get to the interior bathroom.

Dual-Pol: The Game Changer

A few years ago, the NWS upgraded to "Dual-Polarization." Before this, radar only sent out horizontal pulses. It could tell you something was there, but it couldn't tell you exactly what it was. Now, it sends out both horizontal and vertical pulses.

✨ Don't miss: Getting Help at the Apple Store Cumberland Mall Atlanta GA: What You Actually Need to Know

This allows the computer to calculate the shape of the objects. If the object is flat, it’s probably a raindrop. If it’s a chaotic, tumbling mess of different shapes, it’s likely debris. This is the "Tornado Debris Signature" (TDS). When a meteorologist says they "see debris on radar," they aren't looking at the wind anymore; they are looking at pieces of houses and trees lofted into the sky. It’s the most sobering thing you’ll ever hear on a local broadcast.

The Limitation of the "Live" View

Honest moment: nothing you see on your phone is truly "live."

There is a lag. The radar dish has to physically rotate and tilt to scan different levels of the atmosphere. A full "volume scan" can take anywhere from four to ten minutes depending on the mode the NWS is running. By the time that red pixel shows up over your house on an app, the actual storm could have moved two or three miles.

If you’re tracking a fast-moving squall line on I-10, five minutes is an eternity.

Also, beware of "radar smoothing." Many popular apps use algorithms to make the radar looks pretty and fluid. It looks like a smooth lava lamp. This is dangerous. Real weather is blocky and pixelated because the data is collected in "bins." When an app smooths that data, it can literally "erase" a small but intense area of hail or a tight circulation. If you want the truth, use an app that shows the raw data, like RadarScope or the NWS site directly. It’s uglier, but it’s real.

Why Baton Rouge Weather is a Different Beast

We live in a subtropical climate. That sounds fancy, but it basically means we live in a swamp. The moisture levels (precipitable water) here are often off the charts.

This leads to "Pulse Thunderstorms." These are those random afternoon storms that pop up out of nowhere, dump three inches of rain on a single parking lot, and then vanish thirty minutes later. They aren't caused by big cold fronts. They’re caused by the heat of the day.

Standard Baton Rouge doppler weather radar can struggle with these. They develop so fast that they can go from "clear sky" to "severe downburst" in between radar scans. This is why you’ll sometimes get a "Significant Weather Advisory" after the rain has already started. The technology is amazing, but it’s still playing catch-up with the laws of thermodynamics in a Louisiana summer.

The "Anomalous Propagation" Headache

Ever looked at the radar on a clear night and seen a giant circle of "rain" right around the station? That’s not a storm. It’s usually "ground clutter" or "Anomalous Propagation" (AP).

Sometimes, a temperature inversion—where warm air sits on top of cold air—acts like a mirror. It bends the radar beam back down to the ground. The radar sees the tops of trees, buildings, or even heavy traffic on the Mississippi River Bridge and thinks it’s a storm. You can usually tell it’s fake because it doesn’t move. It just sits there, shimmering. Real storms move; ground clutter is static.

Trust, But Verify

If you want to be a local pro at reading the Baton Rouge doppler weather radar, you have to look at more than just the "Reflectivity" (the colors).

- Velocity: This is the wind. Even if the rain doesn't look "purple" or "scary," the velocity map might show 70 mph straight-line winds.

- Correlation Coefficient (CC): This is the "is it all the same stuff" map. If the CC drops in the middle of a storm, the radar is seeing something that isn't rain (like debris). That’s your signal to move to the basement—or the most interior room since we don't have basements in the 225.

- Vertically Integrated Liquid (VIL): This is a fancy way of saying "how much water is in that column of air." High VIL usually means hail. If you see a high VIL core over Perkins Rowe, move your car under a deck.

Practical Steps for the Next Storm

Stop relying on the "daily forecast" percentage. A 40% chance of rain in Baton Rouge doesn't mean it will rain 40% of the time. It means 40% of the area will likely see rain.

When things get spicy, ditch the social media "weather gurus" who post "Hype-casts" with purple maps ten days out. They’re looking for clicks. Instead, go to the source. Bookmark the NWS New Orleans/Baton Rouge page. Download an app that allows you to switch between the Slidell (KLIX), Fort Polk (KPOE), and Lake Charles (KLCH) sites manually.

If you see a storm coming from the northwest, check the Fort Polk radar. It’ll give you a much cleaner look at the storm’s structure before the beam has to travel all the way to Slidell and back.

Lastly, get a NOAA Weather Radio. Radar is a tool, but it requires electricity and an internet connection. When a hurricane or a massive derecho knocks out the cell towers in South Baton Rouge, that $30 radio becomes the most important piece of technology in your house. It’s the direct line from the radar operator’s desk to your living room.

Watch the sky, understand the lag, and never trust a smoothed-out radar map when the clouds start to swirl. Stay weather-aware, because in Louisiana, the weather doesn't care about your plans.