Five hours. That is usually how long it takes to fly from Manila to Tokyo, or maybe finish a decent chunk of a prestige TV series on Netflix. But in the world of Philippine slow cinema, five hours is just the beginning. When people talk about Batang West Side 200, they aren't just talking about a movie; they are talking about a monolithic piece of art that fundamentally shifted how we view the Filipino diaspora. It's long. It's grueling. Honestly, it’s kinda heartbreaking.

Released at the dawn of the millennium, this film didn't just break the rules of conventional storytelling. It smashed them into tiny, black-and-white pieces. Lav Diaz, the director who has since become the godfather of the "duration" movement, used this project to explore a very specific kind of pain. It’s the pain of being a stranger in a strange land. Specifically, Jersey City.

The "200" often associated with the title refers to its place in the timeline of Philippine cinematic milestones, but for most viewers, it’s the sheer weight of the narrative that sticks. We're talking about a murder mystery that refuses to solve itself in any way that feels satisfying. Instead of a "whodunit," it’s a "why-did-we-get-here."

The Gritty Reality of Jersey City’s West Side

Most movies about Filipinos abroad are aspirational. You know the vibe—the hardworking nurse, the sacrificial mother, the ultimate success story. Batang West Side 200 is the polar opposite of that trope. It focuses on the death of Hanzel Harana, a young Filipino boy whose body is found on a cold sidewalk in New Jersey.

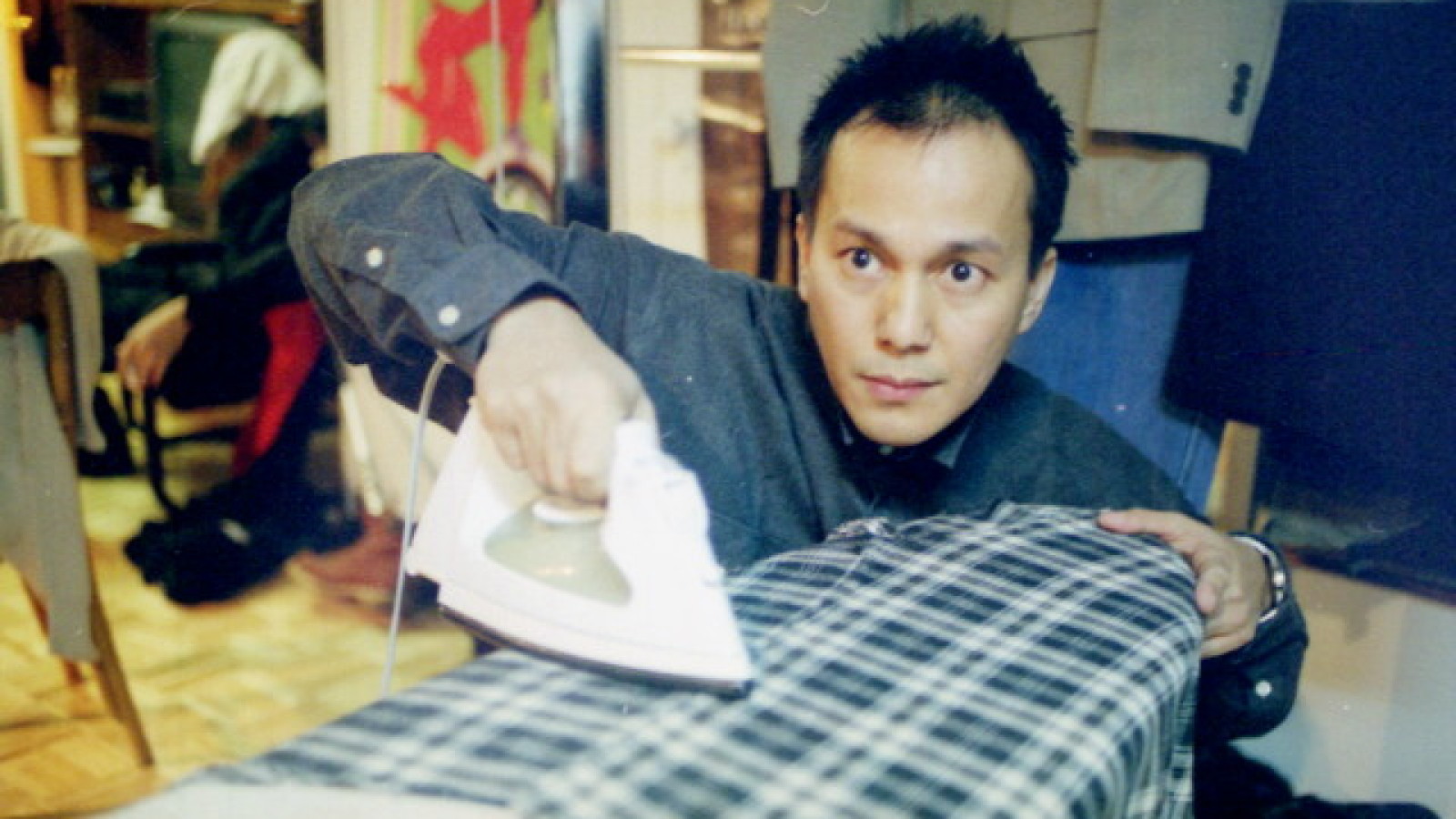

The investigation is led by Juan Mijares, played by Joel Torre with a quiet, simmering intensity that makes your skin crawl. He’s a detective who is also a man drowning in his own past. Through his eyes, we see the Filipino community not as a vibrant, happy group, but as a collection of traumatized individuals hiding from the ghost of the Marcos dictatorship and the crushing weight of the American Dream.

Jersey City isn't a backdrop here. It’s a character. A cold, unforgiving, gray character. Diaz shot on 35mm, but he didn't want the gloss. He wanted the grain. He wanted you to feel the slush on the street.

The film explores "Shabu" addiction, generational trauma, and the way the violence of the Philippines followed these families across the ocean. It’s heavy stuff. If you’re looking for a popcorn flick, this isn’t it. But if you want to understand the psychological cost of migration, you basically have to watch this.

✨ Don't miss: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

Why the Length Actually Matters

I know what you're thinking. Five hours? Really?

Yes.

Lav Diaz has famously said that his films are not "long," they are "free." He rejects the "cinematic time" imposed by Hollywood, which dictates that a story must be wrapped up in 90 to 120 minutes. To Diaz, the Filipino experience is one of waiting. Waiting for visas. Waiting for change. Waiting for justice.

By making Batang West Side 200 five hours long, he forces the audience to sit in that stagnation. You feel the boredom. You feel the slow decay of the characters' hope. In one of the most famous sequences, the camera just lingers. It doesn't move. You start to notice the small things—the way a character breathes, the dust motes in the air, the silence that is never actually silent.

It’s an endurance test, sure. But it’s also a form of respect. He gives these characters the time they were never afforded in real life. He lets them exist without the pressure of a plot point needing to happen every ten minutes.

The Cast That Carried the Weight

The performances in this film are nothing short of miraculous.

🔗 Read more: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

- Joel Torre: As the detective, he serves as our moral compass, though his own needle is spinning wildly.

- Yul Servo: His portrayal of Hanzel (in flashbacks) captures a specific kind of aimless youth that is both frustrating and deeply tragic.

- Gloria Diaz and Angel Aquino: They bring a feminine perspective to a very masculine, violent world, showing how the women in these communities often hold the pieces together until they can’t anymore.

The acting isn't theatrical. It’s observational. Sometimes it feels like you're watching a documentary that someone accidentally stumbled upon. This realism is what helped the film sweep the Gawad Urian Awards and gain international recognition at festivals like Montreal and Singapore.

The Tragedy of the Film's Preservation

Here is something most people get wrong or simply don't know: for a long time, Batang West Side 200 was almost a lost film.

Because it was shot on 35mm and was so incredibly long, the physical prints were massive and expensive to maintain. In the humid climate of the Philippines, film stock is basically a ticking time bomb. For years, the only way to see it was through grainy, low-quality bootlegs or rare festival screenings.

It wasn't until the Austrian Film Museum and other international bodies stepped in to help with restoration efforts that the film was preserved in a way that modern audiences could appreciate. This is a common story in Philippine cinema—so many masterpieces are rotting in warehouses because no one has the budget to save them.

The fact that we can watch a clean version of this movie today is a minor miracle. It’s a reminder that art, especially art that challenges the status quo, is fragile.

The "Shabu" Connection and Social Commentary

You can't talk about this movie without talking about drugs. Long before the "War on Drugs" became a global headline for the Philippines, Diaz was looking at how Shabu (methamphetamine) was tearing through the diaspora.

💡 You might also like: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

In the film, the drug isn't just a vice. It’s a symptom. It’s what people use to cope with the "nothingness" of their lives in the US. They are stuck between a homeland that broke them and a new country that doesn't want them.

The detective's investigation into Hanzel's death reveals a web of complicity. It’s not just one "bad guy." It’s a systemic failure. The film suggests that the trauma of the Philippines' past—specifically the atrocities of the 1970s and 80s—didn't stay in the Philippines. It traveled in the luggage of every immigrant. It’s in their DNA.

Actionable Insights for the Aspiring Cinephile

If you are actually going to sit down and watch Batang West Side 200, don't just dive in blindly. You'll give up in an hour.

- Split it up if you have to. While Diaz prefers you watch it in one go to experience the "immersion," it’s okay to treat it like a miniseries. Watch it in two-hour chunks.

- Contextualize the history. Read a bit about the "First Quarter Storm" and the Martial Law era in the Philippines. The detective’s backstory is tied directly to these events, and the movie won't explain it all to you.

- Focus on the frames. Every shot is composed like a painting. Look at the use of light and shadow. Diaz uses the environment to tell the story as much as the dialogue.

- Embrace the silence. Don't check your phone. The "boring" parts are where the real emotional work happens.

Batang West Side 200 remains a towering achievement because it refuses to apologize for its scale. It demands your time because it believes the subject matter—the soul of the Filipino people—is worth that time. It’s a haunting, beautiful, and ultimately essential piece of world cinema that proves movies don't have to be fast to be powerful. They just have to be honest.

To truly appreciate the film, one must look for the restored versions available through specialized distributors or archival screenings. Avoid the pixelated uploads on streaming sites; the cinematography of Lauro Rene Manda deserves a high-definition screen. Researching the work of the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP) can provide leads on when and where authorized retrospectives of Lav Diaz’s work are being held. Watching his later works like Norte, the End of History or The Woman Who Left can also provide a broader perspective on how his style evolved from the foundations laid in this 2001 masterpiece.