You're staring at a mess of wires and a tiny piece of paper that looks like it was doodled on by a caffeinated spider. It’s frustrating. Most people think they can just wing it when they see a schematic, but basic electrical circuit symbols aren't just suggestions. They are a universal language. If you misread a zigzag for a coil, you aren't just failing a hobby project—you’re potentially melting a breadboard or popping a capacitor that costs more than your lunch.

Drawing these things by hand is a lost art. Honestly, even with modern software like KiCad or Altium, the fundamental logic remains rooted in 19th-century physics. If you want to build anything—from a simple LED flashlight to a custom guitar pedal—you’ve got to speak the language. It’s not about memorization. It’s about understanding the function behind the scribble.

The Battery and the Power Source: Where the Juice Starts

Every circuit needs a heartbeat. In most basic diagrams, you’ll see a series of long and short parallel lines. This is your DC voltage source, usually a battery. The long line is the positive terminal. The short, thicker line is the negative. Simple, right? But here is where people trip up: if you see a circle with a plus and minus inside, that’s an ideal voltage source. It’s a theoretical construct used in textbooks to simplify things, but in the real world, batteries have internal resistance that these symbols don't always show.

Then you have AC power. That’s a circle with a little wavy tilde inside (a sine wave). If you’re messing with AC, you’re dealing with the stuff coming out of your wall. Be careful. A battery might give you a tickle; AC can throw you across the room. Designers use these symbols to dictate the flow of electrons, and if you flip the polarity on a DC symbol while building, you might reverse-bias a component and release the "magic smoke." Once the smoke is out of the chip, you can't put it back in.

Resistors: The Speed Bumps of Electronics

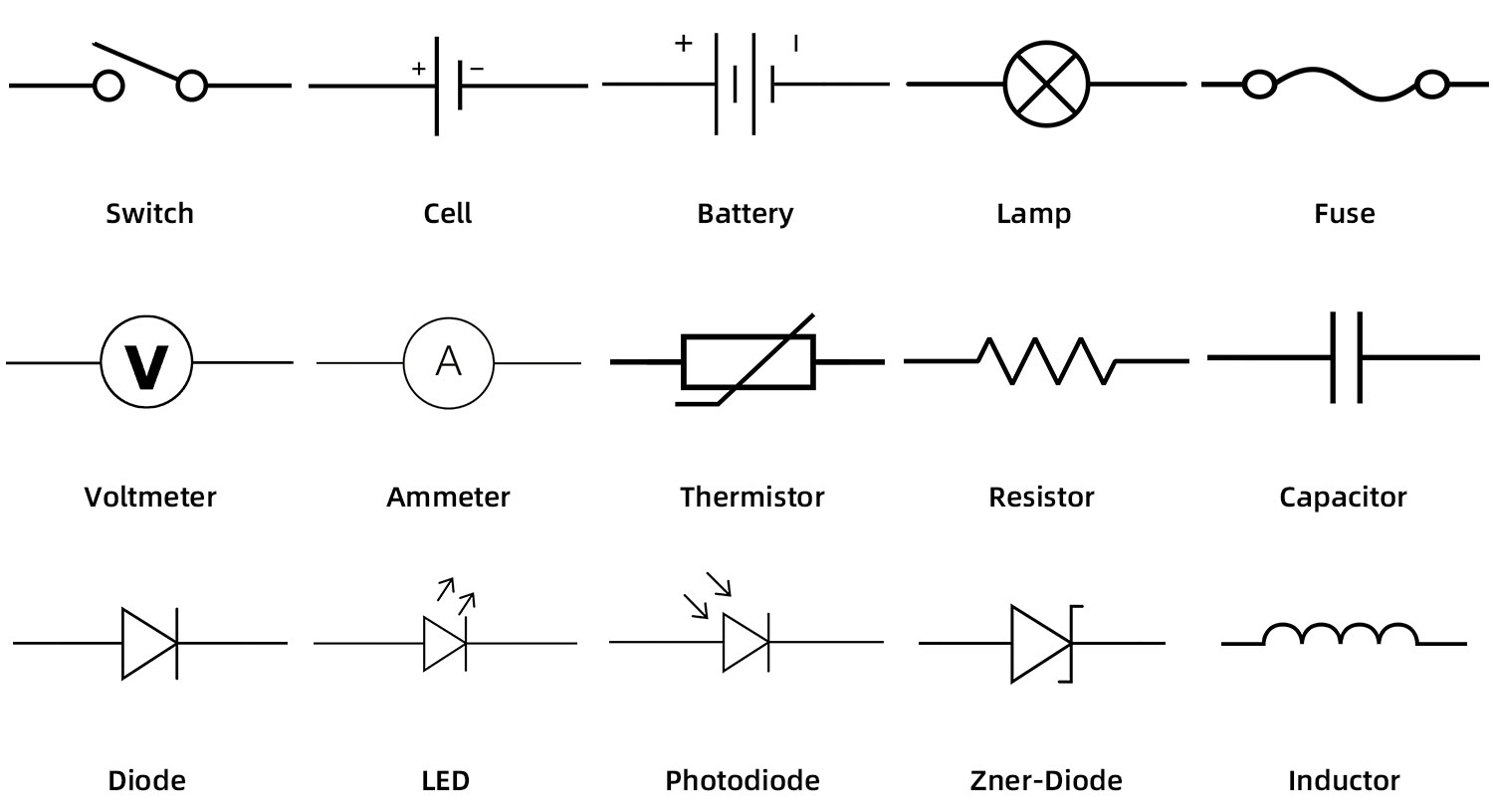

Resistors are the most common basic electrical circuit symbols you'll encounter. In the US and Japan, we use a jagged zigzag line. It looks like a mountain range. In Europe and many other parts of the world, they use a simple hollow rectangle (the IEC standard). Both mean the same thing: "Slow down, electrons."

- The Fixed Resistor: The standard zigzag. It has one job—limit current.

- The Potentiometer: This is a zigzag with an arrow pointing at it. Think of the volume knob on an old radio. It’s a variable resistor. You’re physically moving a wiper across a resistive element to change the value.

- Photoresistors (LDRs): A zigzag inside a circle with two arrows pointing toward it. These change resistance based on light.

If you see a resistor with a diagonal slash through it, that’s usually a rheostat, which is just a fancy way of saying a two-terminal variable resistor. The nuance matters because if you use a fixed resistor where a pot should be, your circuit won't be adjustable. You'll be stuck with one setting forever.

The Gatekeepers: Switches and Relays

A switch is just a break in the line. That’s the easiest way to visualize it. When the line is "up," the circuit is open. No juice. When it’s "down," the circuit is closed. You’ve got flow. But it gets weird when you start looking at SPDT (Single Pole Double Throw) switches. These look like a fork in the road. One input can be toggled between two different outputs.

👉 See also: Finding the Right Jigsaw Puzzle Making Machine Without Getting Ripped Off

Then there’s the relay. A relay is basically a switch operated by an electromagnet. In a schematic, you’ll see a coil (a series of loops) next to a switch symbol. When current hits the coil, it creates a magnetic field that pulls the switch shut. It's how a tiny 5V signal from an Arduino can turn on a massive 120V motor without frying the microcontroller. It’s isolation in its purest form.

Capacitors: The Tiny Buckets of Energy

Capacitors are everywhere. They look like two parallel lines with a gap between them. This represents the physical construction of a capacitor: two conductive plates separated by an insulator (a dielectric). If the lines are straight, it’s a non-polarized capacitor. You can plug it in any way you want.

However, if one line is curved or has a plus sign next to it, that’s an electrolytic capacitor. You must orient these correctly. If you put an electrolytic capacitor in backward, it can literally explode. I’ve seen them pop like firecrackers in a lab. It’s loud, it’s smelly, and it’s a rookie mistake that can be avoided if you just pay attention to that little curved line in the symbol.

Diodes and the One-Way Street

A diode is a triangle pointing at a vertical line. Think of it as a one-way valve for electricity. Current flows in the direction the triangle points (anode to cathode) but is blocked from going the other way. This is crucial for protecting circuits from reverse polarity.

- LEDs: A diode symbol with two little arrows pointing away from it. The arrows represent light being emitted.

- Zener Diodes: These have a little "Z" shape on the vertical bar. They are designed to allow current to flow backward once a certain voltage is reached. They are the unsung heroes of voltage regulation.

- Schottky Diodes: These have a distinct "S" shape on the bar and are used for fast switching.

Grounds: The Most Misunderstood Symbol

Every circuit needs a reference point. That’s the ground. But not all grounds are created equal.

The "Chassis Ground" looks like a pitchfork or a rake. It means the circuit is connected to the metal casing of the device.

The "Earth Ground" is a vertical line with three horizontal lines of decreasing width. This means a literal connection to the dirt outside your house via a copper rod.

Then there’s "Signal Ground" or "Common," often shown as a simple downward-pointing triangle.

📖 Related: Dreame X40 Ultra: What Most People Get Wrong

Mixing these up is a recipe for noise. If you’re building an audio amplifier and you tie your signal ground to a noisy power ground, you’re going to hear a constant hum. It’s the bane of every hobbyist’s existence. Keep your grounds clean.

Logic Gates: The Brains of the Operation

If you’re looking at digital electronics, basic electrical circuit symbols shift from physical components to logical operations. You’ll see D-shapes (AND gates) and curved triangle shapes (OR gates).

- AND Gate: Both inputs must be "on" for the output to be "on."

- OR Gate: Either input can be "on."

- NOT Gate: A triangle with a tiny circle (an inversion bubble) at the tip. It flips the signal. 1 becomes 0.

These aren't physical parts you can usually buy as a single gate; they are usually packed into Integrated Circuits (ICs). When you see a large rectangle with many pins in a schematic, that’s an IC. Each pin is numbered, and you have to cross-reference the datasheet from the manufacturer (like Texas Instruments or Analog Devices) to know what each pin actually does.

Real-World Nuance: Why Standards Vary

It would be great if everyone used the same symbols. They don't. The IEEE/ANSI standards are dominant in the US, while the IEC standards rule Europe. If you're looking at a vintage British radio schematic from the 1950s, it’s going to look alien compared to a modern Silicon Valley startup’s board file.

For instance, an inductor (a coil of wire) is shown as a series of humps in the US. In Europe, it’s often just a solid filled-in rectangle. If you mistake a European inductor for a US resistor, your circuit is doomed. Always check the legend or the "Notes" section of a professional schematic before you start soldering.

Surprising Details: The "Dot" Convention

Wires cross each other all the time in drawings. How do you know if they are connected? The Dot. If there is a solid black dot where two lines intersect, they are joined. If there is no dot, they are just passing over each other like ships in the night. Some older schematics use a little "hump" or bridge to show a wire jumping over another, but the dot convention is the modern standard. If you miss a dot, you miss a connection, and your circuit will be "open" exactly where it needs to be "closed."

Practical Steps for Mastering Circuit Symbols

Don't try to memorize them all at once. It’s useless. Instead, take a physical device—something simple like an old toy or a broken remote—and try to find its "service manual" online. Look at the schematic while looking at the physical board.

- Trace the Power: Find the battery symbol and follow the line. Where does it go first? Usually a switch or a fuse.

- Identify the Passives: Locate the resistors and capacitors. Notice how they are clustered. Capacitors are often near the power pins of chips to "smooth" the voltage.

- Find the Ground: See how many different points on the board all lead back to that same ground symbol.

- Use a Simulator: Download a free tool like LTspice or use a web-based one like EveryCircuit. Pick a symbol, drop it in, and hit "play." Seeing the virtual electrons move helps bridge the gap between a static symbol and a living circuit.

Building a mental map of basic electrical circuit symbols is about pattern recognition. After a while, you don't see "zigzag, triangle, parallel lines." You see "current limiter, signal gate, energy storage." You start seeing the "intent" of the engineer who designed it.

Start by drawing your own simple circuits. Draw a battery, a switch, and a light bulb (a circle with an 'X' or a loop inside). Then add a resistor to protect the bulb. Once you've drawn it, build it. The connection between the ink on the paper and the glow of the light is where the real learning happens.

Check your local library for the ARRL Handbook or Forrest Mims III’s Getting Started in Electronics. Mims' books are hand-lettered and hand-drawn, making the symbols feel much more approachable and "human" than a cold, CAD-generated PDF. If you can read his diagrams, you can read anything.

Next time you open up a piece of gear, don't just see a maze. Look for the landmarks. Find the ground, trace the power, and respect the diodes. You'll spend a lot less time replacing blown fuses and a lot more time actually making things work.