Ask three different fans who the goat is and you’ll get four different answers. Seriously. It’s the kind of debate that starts with career home runs and ends with someone shouting about the dead-ball era or the "steroid taint."

Baseball greatest players of all time isn't just a list; it’s a massive, messy argument spanning over a century of box scores.

Honestly, we’re living in a weirdly lucky time for this conversation. It’s January 2026. We’ve just watched Shohei Ohtani lock up his fifth MVP in six years. He’s basically broken the game. But does a guy with two World Series rings and a 50-50 season actually top a legend like Babe Ruth who literally out-homered entire teams?

It's a lot to process.

The Immortal Three: Ruth, Mays, and Bonds

If you look at Wins Above Replacement (WAR)—which is basically the nerd-approved way to see how much a player actually matters—three names always rise to the top.

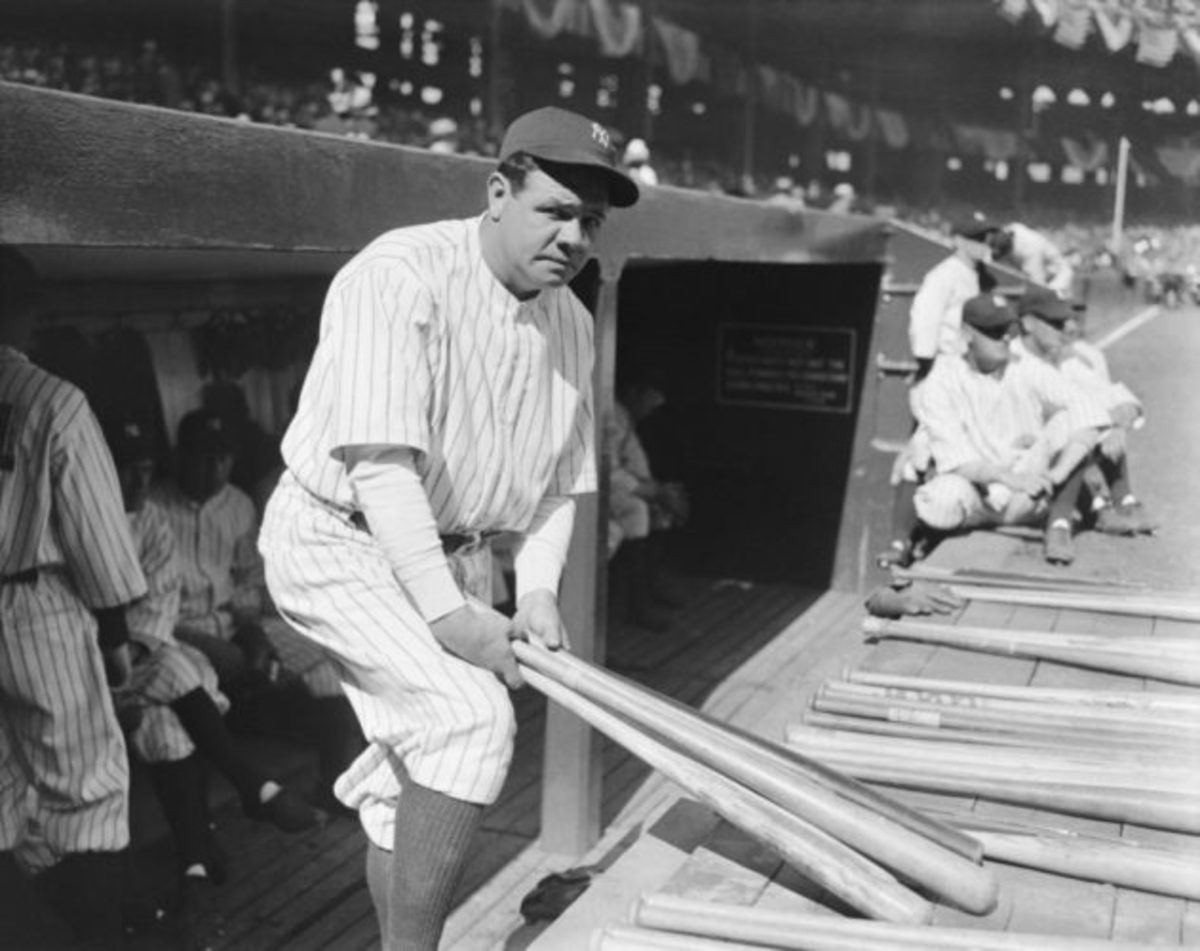

Babe Ruth is the obvious starting point. Before he arrived, home runs were basically accidents. He hit 714 of them. But people forget he was also a lights-out pitcher for the Red Sox, posting a career 2.28 ERA before the Yankees decided he was too good with a bat to leave on the mound.

Then there’s Willie Mays.

Mays is often called the "perfect" ballplayer. He had the speed, the glove, and the power. He finished with 660 homers and 12 Gold Gloves. If he hadn’t missed nearly two seasons for military service, he’s probably sitting on 700+ homers easily.

📖 Related: How to watch vikings game online free without the usual headache

Then we get to Barry Bonds. This is where it gets spicy.

Bonds is the only member of the 500-500 club. 500 homers and 500 steals. In fact, nobody else even has 400-400. His 762 career home runs are the gold standard, even if the Hall of Fame voters are still acting like he doesn't exist. By the time he was intentionally walked 120 times in a single season (2004), pitchers were basically terrified to even look at him.

Pitching Royalty: Beyond the Strikeout

We can't talk about the greats without mentioning the guys on the bump.

Walter Johnson—The Big Train—was throwing gas before anyone knew what a radar gun was. He had 110 career shutouts. Think about that. Modern pitchers are lucky to get two in a career.

Then you have Cy Young, whose name is on the trophy for a reason. 511 wins. That record is never being broken. Not in a world where starters barely go six innings.

And then there's Nolan Ryan.

5,714 strikeouts. He threw seven no-hitters and was still hitting 95 mph in his mid-40s. He’s the ultimate outlier.

👉 See also: Liechtenstein National Football Team: Why Their Struggles are Different Than You Think

The Ohtani Problem

Is it too early to put Shohei Ohtani in this tier?

Maybe. But consider this: in 2024, he became the first 50-50 player ever. Then in 2025, he came back to the mound, helped the Dodgers win another World Series, and grabbed another MVP. He is doing things Ruth only did for a few seasons, and he's doing them against a global talent pool that is exponentially better than what existed in 1920.

He’s already at roughly 51.5 career WAR by age 31. If he stays healthy for another five years, the GOAT conversation changes forever.

The Guys History Tends to Forget

It’s easy to focus on the icons, but the baseball greatest players of all time list has some deep cuts that deserve more love.

Take Stan Musial. "Stan the Man" was so consistent it was almost boring. He had 1,815 hits at home and 1,815 hits on the road. Perfection.

Or Josh Gibson.

Gibson never got to play in the MLB because of the color barrier, but legend says he hit nearly 800 home runs in the Negro Leagues. The recent integration of Negro League stats into the MLB record books has finally started to give guys like Gibson and Oscar Charleston their due.

✨ Don't miss: Cómo entender la tabla de Copa Oro y por qué los puntos no siempre cuentan la historia completa

Then there's Rickey Henderson.

He didn't just steal bases; he changed how the game was played. 1,406 steals. The gap between him and second place (Lou Brock at 938) is the size of a whole career.

Why the Rankings Always Shift

The reason we can’t agree is that the game has changed so much.

- The Dead-Ball Era: Before 1920, the ball was soft and gross. Pitchers like Christy Mathewson dominated because nobody could hit the "mush-ball" over the fence.

- Integration: Before 1947, the "greatest" lists were incomplete. You can't say someone was the best when they weren't playing against everyone.

- The Expansion Era: More teams meant more travel and specialized bullpens.

- The Analytical Era: Now we know that batting average isn't nearly as important as On-Base Percentage (OBP).

Ted Williams, for example, had a career .482 OBP. He basically reached base half the time he stepped up. That’s insane. He’s the "greatest pure hitter" for a reason.

Actionable Takeaway: How to Judge Greatness

If you're trying to settle a bar bet or just understand the history better, don't just look at the back of a baseball card.

- Look at ERA+ and OPS+: These stats compare a player to their specific era. A 150 OPS+ means that player was 50% better than the average player of their time.

- Check the WAR per 162 games: This helps you see how dominant a player was regardless of injuries or short careers (looking at you, Sandy Koufax).

- Contextualize the Negro Leagues: Use the updated MLB databases to see how legends like Satchel Paige stack up against their white contemporaries.

The debate is the point. That's why we love this game.

To really dive deep, start by comparing the "peak" years of Barry Bonds (2001-2004) against the peak of Babe Ruth (1920-1923). You'll find that while the eras are different, the sheer gap between them and the rest of the league is almost identical.

Go watch some old film of Willie Mays playing center field. You'll see why the stats only tell half the story. The way he moved, the way he anticipated the ball—that’s the "eye test" that numbers can’t quite capture yet.