You’re staring at a weird bump in the mirror. It’s been there for months. Maybe it bled once when you caught it with a towel, but then it healed up, so you figured it was just a stubborn zit or a nick from shaving. Now you’re scrolling through basal cell carcinoma photos late at night, trying to play detective with your own skin. It’s stressful. Honestly, the internet makes it worse sometimes because every "classic" photo looks like a giant, crusty crater, but that’s not always how this starts.

Skin cancer is sneaky. Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common form of cancer globally, but it’s also the most diverse in how it shows up. Some people get a pearly, shiny bump. Others get a flat, red patch that looks like eczema. Some even get a scar-like lesion that appears out of nowhere without an injury. If you’re looking at photos to decide if you should see a doctor, you need to know that what you see on a high-res medical site might not match the subtle change happening on your nose or shoulder.

What those basal cell carcinoma photos are actually showing you

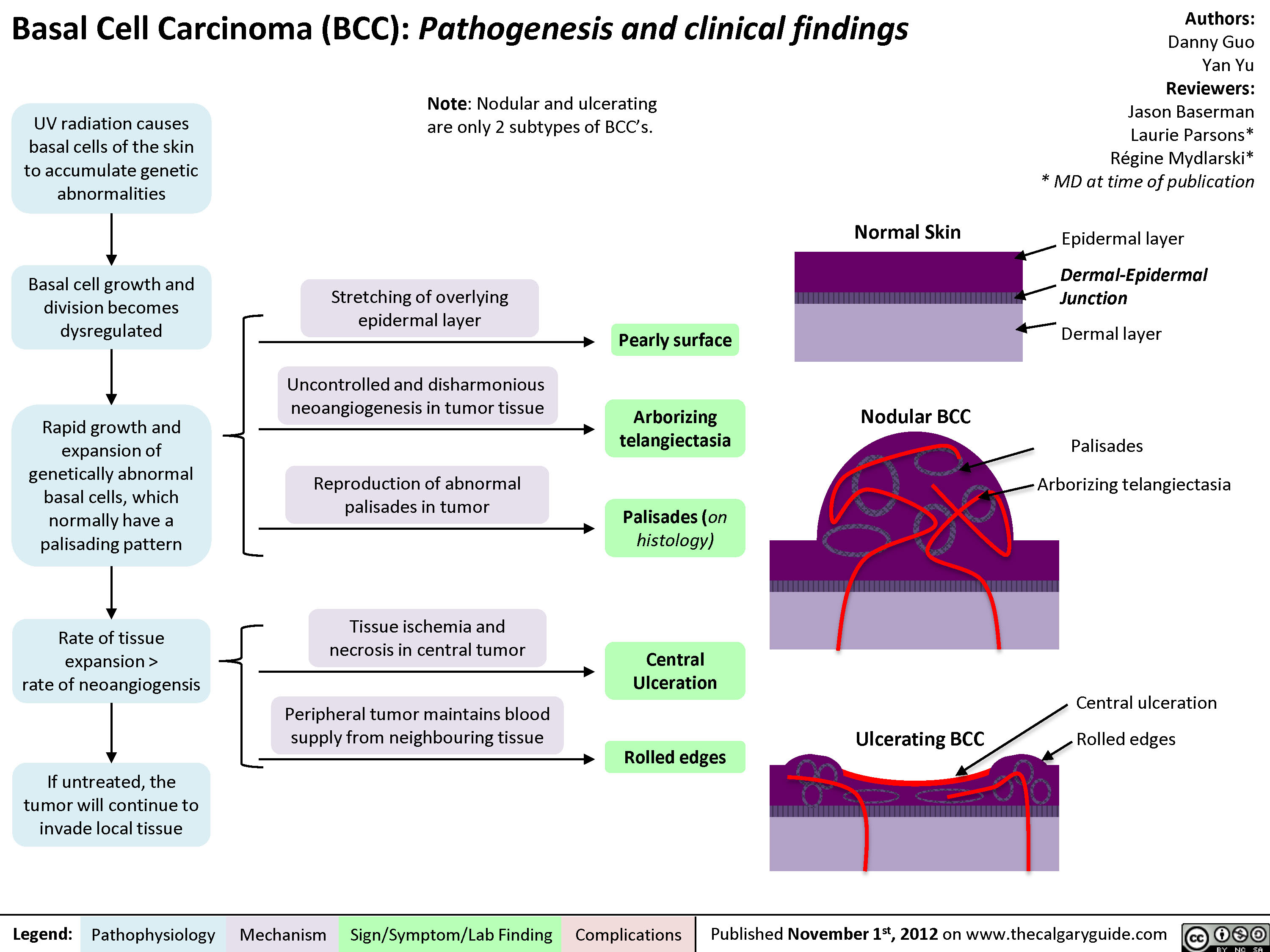

When you look at a gallery of BCC images, you’re usually seeing the "Nodular" type. This is the poster child for basal cell. It looks like a little dome. If you look closely at these photos, you’ll see tiny, thin red lines snaking across the surface. Doctors call these telangiectasias. They are broken blood vessels. These bumps often have a "pearly" border, which basically means they catch the light a certain way, looking a bit like a translucent bead tucked under the skin.

But here is the kicker: BCC can look like a lot of "boring" things.

It might look like a patch of dry skin that never goes away despite using the most expensive moisturizer in your cabinet. This is the "Superficial" type. In photos, these look like scaly, reddish plaques. They’re common on the back or chest. People mistake them for psoriasis or ringworm for years. The difference? BCC won't respond to antifungal creams or steroid ointments. It just stays. It grows—very slowly, but it grows.

Then there’s the "Morpheaform" or sclerosing BCC. These are the ones that really mess with your head. They don't look like "cancer" in the way we're taught. In photos, they look like a firm, yellowish-white scar with undefined edges. If you have a scar in a place where you never had a cut, burn, or surgery, that’s a massive red flag. These are actually more aggressive because they grow like roots underground, spreading further than what you can see on the surface.

Why lighting and camera quality change everything

Ever notice how a mole looks terrifying in a blurry basement selfie but totally fine in natural sunlight? Or vice versa? Professional basal cell carcinoma photos used by dermatologists are often taken with a dermatoscope. This is a handheld tool that uses polarized light to see through the top layer of skin (the stratum corneum).

When a pro looks at your skin, they aren't just looking at the "bump." They are looking for "leaf-like structures" at the edge of a lesion or "large blue-gray ovoid nests" deep in the dermis. You can’t see those with the naked eye. This is why self-diagnosis via Google Images is a recipe for anxiety. You might be looking at a benign sebaceous hyperplasia (an enlarged oil gland) and thinking it’s a malignancy because they both can have a central dimple.

📖 Related: Thinking of a bleaching kit for anus? What you actually need to know before buying

The "Pearly" Myth and Other Misconceptions

We talk a lot about the pearly glow. It’s the classic description. However, if you have a darker skin tone—Fitzpatrick scale IV, V, or VI—BCC often contains pigment. In these cases, basal cell carcinoma photos show brown or black spots.

This is a huge problem in medical education. For decades, textbooks mostly showed BCC on very fair-skinned Caucasians. If you have brown skin, your BCC might look more like a dark mole or even a melanoma. Research published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology has highlighted that pigmented BCC is much more common in Hispanic and Asian populations than previously emphasized. If you’re only looking for "pink and pearly," you’re going to miss it.

It’s not just about the sun

Yes, UV radiation is the primary culprit. We know this. Dr. Henry Lim and other experts in photodermatology have proven the link between intermittent intense sun exposure (sunburns) and BCC. But it’s not just about where the sun hits.

You can get BCC in places that have never seen the light of day. While it’s rare, it happens. It can be linked to genetic predispositions, like Gorlin syndrome, or previous exposure to arsenic or radiation treatments. So, if you find a weird, non-healing sore in a "hidden" spot, don't dismiss it just because you always wore a shirt.

Comparing BCC to its "Cousins"

It’s easy to get confused when looking at skin cancer galleries. You’ll see Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) and Melanoma right next to the BCC photos.

SCC often looks "angrier." It’s usually crustier, more prone to bleeding, and feels more like a hard wart. BCC is generally slower-moving. It’s often described as the "good" cancer to get if you have to have one, which is a bit of a weird thing to say, but it’s because it rarely spreads (metastasizes) to other organs. It stays local.

However, "local" can still mean losing a chunk of your nose or ear if you let it go too long.

👉 See also: The Back Support Seat Cushion for Office Chair: Why Your Spine Still Aches

I’ve seen cases where a tiny spot the size of a grain of rice ended up requiring a Mohs surgery that took three stages to clear. Why? Because the tumor had "fingers" reaching out under the skin that weren't visible in the initial basal cell carcinoma photos. The surface is just the tip of the iceberg.

The "Ugly Duckling" Sign

Dermatologists often use the "Ugly Duckling" rule. If you have a bunch of spots on your arm and they all look like little brown freckles, but one looks like a pinkish, shiny smudge—that’s the ugly duckling. It doesn’t fit the pattern of your body. That’s usually the one that needs a biopsy.

The biopsy: Beyond the photo

A photo is a 2D representation of a 3D problem. Once you go to a dermatologist, they will likely perform a shave biopsy if they suspect BCC. They numb the area—it feels like a tiny pinch—and take a thin slice.

Under the microscope, a pathologist looks for specific clusters of basaloid cells. They look for "peripheral palisading," which is basically a fancy way of saying the cells at the edge of the cluster line up like a picket fence. This is the gold standard. No matter how many basal cell carcinoma photos you look at, you can’t get a definitive answer without those cells being checked under a lens.

Treatment is more than just "cutting it out"

If your spot matches the photos and the biopsy comes back positive, don't panic. You have options.

For superficial types, there are creams like Imiquimod (Aldara). It’s basically a way to trick your immune system into attacking the cancer cells. It makes the area look pretty gnarly for a few weeks—red, scaly, and sore—but it works well for thin lesions.

Then there’s C&D (Curettage and Desiccation). The doctor scrapes the tumor out and then uses an electric needle to kill any remaining cells. It’s quick. It heals like a cigarette burn.

✨ Don't miss: Supplements Bad for Liver: Why Your Health Kick Might Be Backfiring

For the face, Mohs Micrographic Surgery is the gold standard. Developed by Dr. Frederic Mohs in the 1930s (and refined since), it involves removing a layer of skin and checking it under the microscope immediately while you wait. If there’s still cancer at the edges, they take another layer. This preserves the most healthy tissue possible, which is kinda important when you’re dealing with your eyelid or your nose.

Practical steps you can take right now

Stop scrolling through Google Images for a second. It's likely just making you vibrate with anxiety.

Instead, do a self-exam. Grab a handheld mirror and a full-length one. Check your scalp, the backs of your ears, and even between your toes. If you find something, take your own basal cell carcinoma photos.

Use a clear, well-lit area. Put a ruler or a coin next to the spot so you can track its size. Take a photo today, and then take another one in three weeks. If it has changed, bled, or hasn't healed in that time, call a dermatologist. Tell the receptionist, "I have a non-healing lesion that I'm concerned is skin cancer." That usually gets you an appointment faster than saying you want a general skin check.

Remember that BCC is almost 100% curable when caught early. The goal isn't to be a doctor; it’s to be an advocate for your own skin. If something feels "off," it probably is. Don't wait for it to look like the scary photos in a textbook.

Your Skin Health Checklist:

- Look for the "sore that won't heal." If a spot scabs over, looks better, and then breaks open again, that’s a classic BCC sign.

- Check for the "pearly" sheen. Use a flashlight at an angle to see if the edges of a bump reflect light differently than the surrounding skin.

- Identify new "scars." If you see a white, waxy, or taut area where you haven't been injured, mention it to a professional immediately.

- Monitor the "boring" red patches. Don't assume that a persistent dry patch is just eczema, especially if it's in a sun-exposed area.

- Document everything. High-quality photos taken over several weeks are incredibly helpful for your doctor to see the "behavior" of the spot.

Once you’ve identified a suspicious area, the next step is a professional evaluation. Avoid the temptation to use "black salve" or "natural" caustic pastes you might find online; these can cause horrific scarring and often leave the cancer roots deep in your skin to grow undetected. Stick to evidence-based care from a board-certified dermatologist.