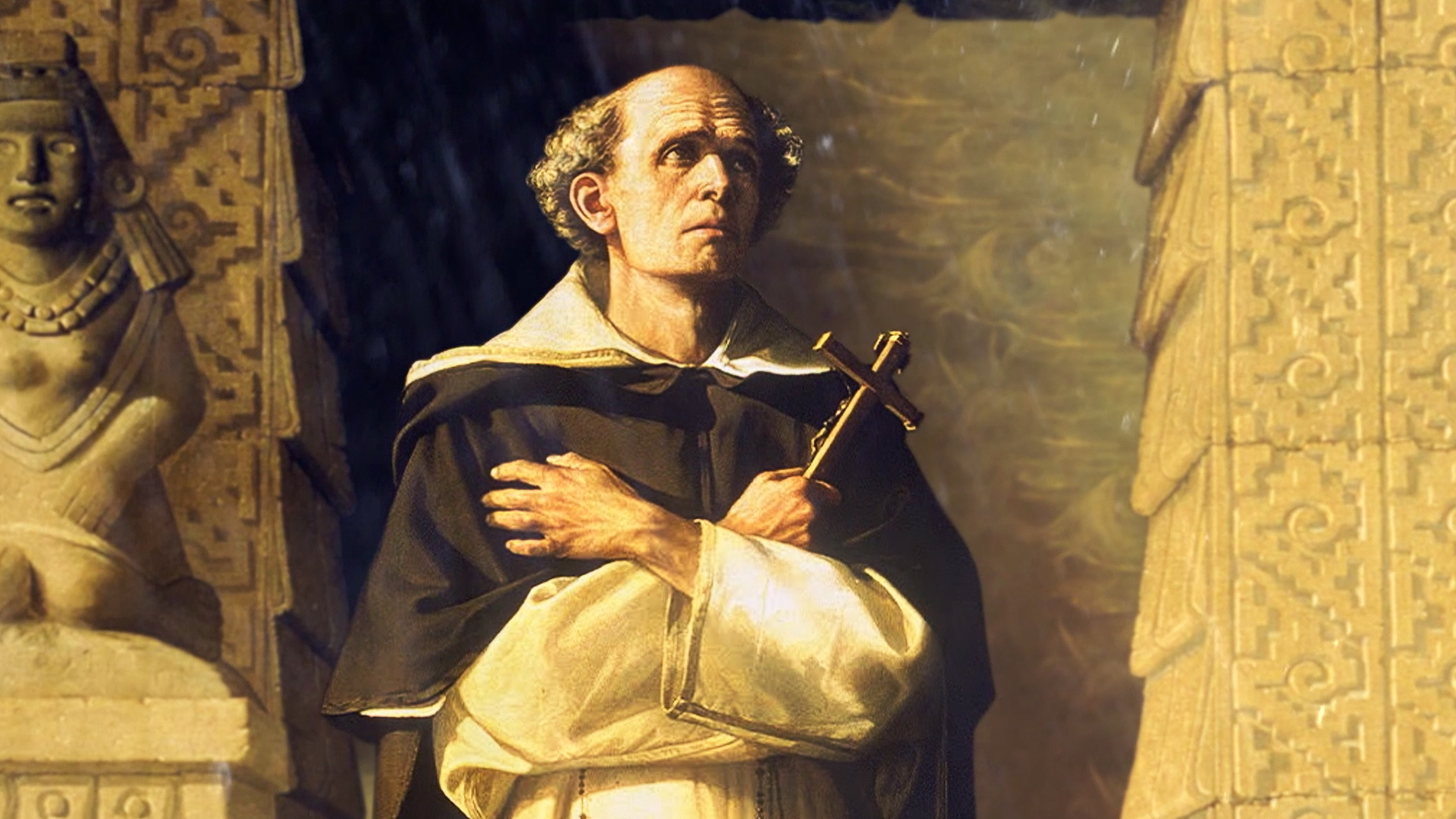

History isn’t a clean story. It’s messy. If you look at the early 1500s through a modern lens, it’s easy to see villains and victims, but the reality of Bartolomé de las Casas is way more complicated than the "saintly priest" image you might have seen in a high school textbook. He was a man of his time who somehow managed to grow a conscience in the middle of a gold rush.

He didn't start as a hero. Far from it.

When Las Casas first arrived in Hispaniola in 1502, he was just another guy looking to get rich. He was an encomendero. Basically, that meant he owned land and, by extension, the forced labor of the indigenous people living on it. He participated in slave-raiding expeditions. He profited from a system that was literally working people to death. He was part of the problem.

Then something clicked.

It wasn't a sudden lightning bolt. It was a slow burn of guilt and observation. He saw the population of the Caribbean islands collapsing—not just from disease, which is the common narrative today, but from sheer, brutal exhaustion and systemic violence. By the time he gave his famous 1514 Pentecost sermon, he’d decided to give up his slaves and his land. He spent the next fifty years screaming at the Spanish Crown to stop the genocide.

But here’s the thing: his legacy is stained by one of the biggest "what-ifs" in history.

The Great Debate: Sepúlveda vs. Las Casas

In 1550, something happened in Valladolid, Spain, that sounds like a plot from a legal drama. The King of Spain actually paused all military conquests in the Americas to hold a formal debate. Can you imagine that today? A global superpower stopping its expansion because of an ethical query?

👉 See also: Statesville NC Record and Landmark Obituaries: Finding What You Need

On one side, you had Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda. He was a scholar who used Aristotle to argue that indigenous peoples were "natural slaves." He thought they were inferior and that Spain had a divine right to rule them by force.

On the other side stood Bartolomé de las Casas.

He argued for five straight days. He didn't just talk about religion; he talked about human rights before "human rights" was even a term. He argued that the American Indians were rational, civilized, and fully capable of self-governance. He claimed the only way to spread Christianity was through peace and persuasion, not the sword.

The outcome was weirdly indecisive

Neither side "won" in a way that changed everything overnight. The wars didn't stop. But the debate shifted the entire legal framework of the Spanish Empire. It led to the New Laws of 1542, which—at least on paper—abolished the enslavement of indigenous people.

Of course, the colonists in the New World hated this. They practically started a civil war in Peru over it. Las Casas became one of the most hated men in the Spanish colonies. He was a traitor to his class. He was a "social justice warrior" of the 16th century, and he had the scars to prove it.

The Dark Side of the Reformer

We have to talk about the huge mistake Las Casas made. It's the part people skip over when they want a clean hero. In his early days as an advocate, Las Casas suggested that if the Spaniards stopped enslaving the indigenous population, they should instead import enslaved people from Africa.

✨ Don't miss: St. Joseph MO Weather Forecast: What Most People Get Wrong About Northwest Missouri Winters

He thought African people were "stronger" and could handle the labor.

It was a catastrophic error. He eventually realized how wrong he was and wrote about his deep regret, but the damage was done. His early support for the transatlantic slave trade provided a moral loophole that others exploited for centuries. By the end of his life, he viewed the enslavement of Africans as just as cruel and unjust as the treatment of the Taíno, but history rarely lets you take back a mistake of that magnitude.

Honestly, it’s a reminder that even the most "progressive" people are limited by the blind spots of their era. He was trying to solve one atrocity and accidentally fueled another.

The "Black Legend" and Real History

If you've ever heard that the Spanish were uniquely evil compared to the British or the French, you've encountered the "Black Legend." Interestingly, Bartolomé de las Casas is the primary source for it.

His book, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, was a bestseller. He wrote it to shock the King into action. He used graphic, horrifying descriptions of violence—babies being thrown into rivers, people being burned alive on grids.

- The Propaganda War: The British and Dutch, who were Spain's rivals, took his writings, translated them, and added gruesome illustrations.

- The Intent: Las Casas wasn't trying to make Spain look bad to the world; he was trying to save souls and lives.

- The Result: His work became a tool for other colonial powers to justify their own "gentler" brands of colonization (which, spoiler alert, weren't actually gentler).

Historians today argue about his numbers. Las Casas claimed millions died in specific incidents where modern archaeology suggests the numbers were smaller. But focusing on whether he exaggerated a death count from 10,000 to 100,000 kinda misses the point. The systemic destruction was real. The trauma was real.

🔗 Read more: Snow This Weekend Boston: Why the Forecast Is Making Meteorologists Nervous

Why Las Casas Matters in 2026

It’s easy to dismiss a 500-year-old priest. But Las Casas is actually the grandfather of international law.

Before him, the law of the land was basically "might makes right." If I can conquer you, I own you. Las Casas challenged that. He insisted that there are universal rights that belong to every human being regardless of their religion or "level of civilization."

He spent his final years in Spain, acting as a sort of unofficial lobbyist for the indigenous people he left behind. He was a prolific writer, a tireless traveler, and a massive pain in the neck for the Spanish bureaucracy.

What he actually achieved:

- Legal Precedents: He helped establish the idea that the "consent of the governed" was a thing, even in a monarchy.

- Ethnographic Records: His Historia de las Indias is one of the most important sources we have for understanding what life was like before and during the conquest.

- Moral Accountability: He forced an empire to look in the mirror and acknowledge its own cruelty.

Las Casas didn't stop the conquest. He didn't save everyone. But he made it impossible for the world to pretend it didn't know what was happening.

How to Understand His Legacy Today

If you want to dive deeper into the life of Bartolomé de las Casas, don't just read the summaries. Look at the primary sources.

- Read the "Short Account": It’s short, brutal, and surprisingly modern in its anger.

- Visit Santo Domingo: You can still see the places where these debates happened. The physical history is still there in the stones of the oldest cathedrals in the Americas.

- Study the Valladolid Debate: It’s the best way to understand how Europeans tried to justify colonialism and how Las Casas dismantled their logic piece by piece.

The most important takeaway is that change usually comes from people who were once part of the system they end up fighting. Las Casas was an insider who broke ranks. He was flawed, he made terrible mistakes regarding African slavery, and he was often a demographic exaggerator.

But he was also one of the first people to say, "No, this is wrong, and I don't care if it's legal or profitable." That’s a lesson that doesn't get old.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge:

- Examine the New Laws of 1542 to see how Las Casas's advocacy translated into actual legislative attempts, even if enforcement was weak.

- Compare his writings with those of Bernal Díaz del Castillo to see the stark contrast between a soldier’s perspective and a reformer’s perspective on the same events.

- Track the evolution of his views on African slavery through his later writings in Historia de las Indias, where he admits his "blindness" and expresses his fear of divine judgment for his earlier suggestions.