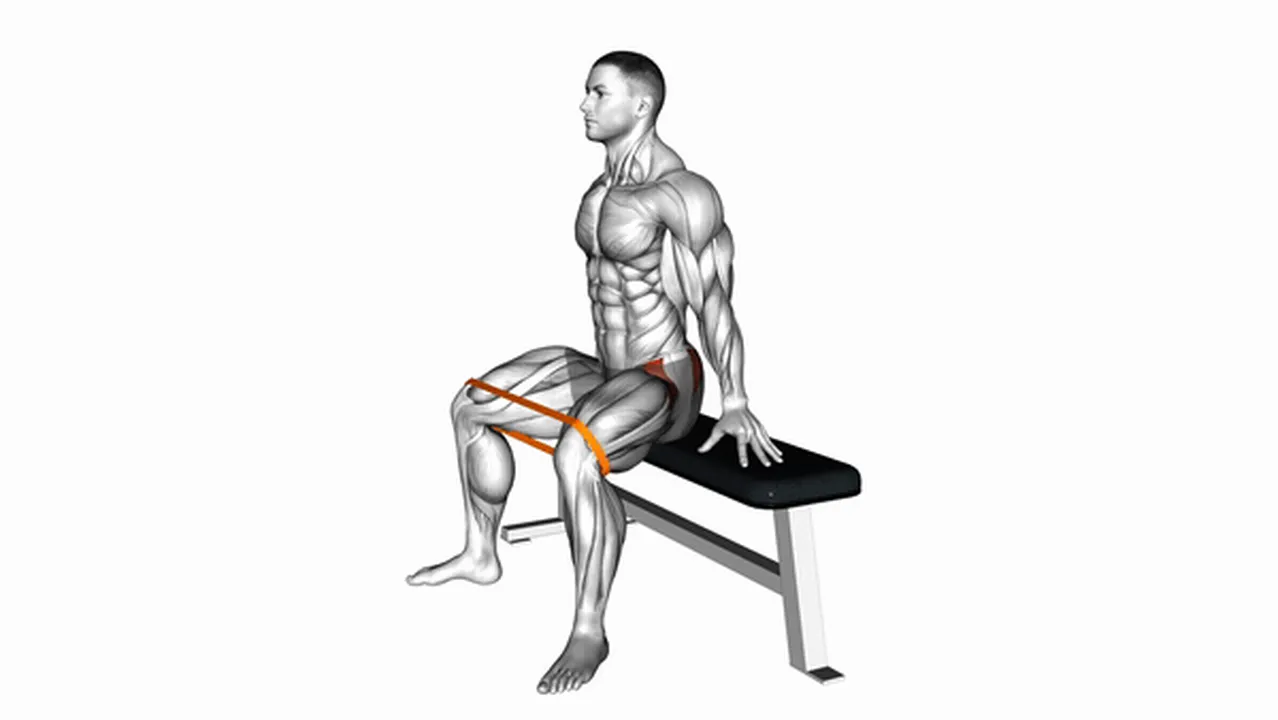

You’re sitting on the edge of a weight bench, a looped resistance band cinched around your thighs just above the knees. Your feet are planted, shoulders back, and you start pulsing your knees outward against the tension. It feels like a burn. A deep, localized, "please make it stop" kind of fire in the sides of your hips. This is the band seated hip abduction, and honestly, it’s one of the most misunderstood movements in the modern gym landscape.

Most people treat it as a finisher. They tack it onto the end of a leg day to "feel the pump" before hitting the showers. But if you're dealing with "sleepy glutes" or knee cave during your heavy squats, this move is actually a foundational requirement, not an optional extra.

The gluteus medius and minimus—the muscles responsible for this outward movement—are tiny compared to the gluteus maximus. Yet, they are the primary stabilizers of your pelvis. When they’re weak, everything else falls apart. Your knees collapse inward (valgus). Your lower back starts taking the load during deadlifts. Suddenly, you’re wondering why your hips feel "tight" when they’re actually just incredibly weak.

The Mechanics of the Lateral Glutes

Let's get technical for a second. The band seated hip abduction primarily targets the abductor group, specifically the gluteus medius, the gluteus minimus, and the tensor fasciae latae (TFL). Because you are seated, you’ve effectively taken the hamstrings out of the equation. You’ve also shortened the hip flexors. This isolation is exactly why that burn happens so fast.

In a standing position, your body has a million ways to cheat. You can lean your torso. You can use momentum. Seated? You’re locked in.

There’s a common misconception that more resistance is always better. People grab the "XX-Heavy" black band, shove their knees out two inches, and call it a set. You’re better off using a medium band and focusing on the end-range contraction. Research by experts like Dr. Bret Contreras, often called "The Glute Guy," suggests that the glutes respond exceptionally well to high metabolic stress. This means higher reps and longer "time under tension" usually beat out raw, heavy resistance for this specific movement.

Why Your Feet Placement Changes Everything

Where you put your feet dictates which part of the hip you’re actually hitting. If your feet are tucked narrow and close to the bench, you’re working in a different range of motion than if they are set wide.

Try this: Set your feet wider than your hips before you even start the movement. Now, push outward. You’ll notice the tension is constant. If you start with your knees touching, there is a "dead zone" at the beginning of the rep where the band is slack. Avoid the slack. Keep the band taut from the first millisecond to the last.

✨ Don't miss: National Breast Cancer Awareness Month and the Dates That Actually Matter

The "Lean" Secret Most Trainers Miss

If you watch someone do the band seated hip abduction in a physical therapy clinic, they are usually sitting bolt upright. That’s fine for basic activation. However, if you want to bias different fibers of the glute medius, you need to play with your torso angle.

- The Forward Lean: Hinging forward at the hips while performing the abduction puts the gluteus medius in a more lengthened position. For most, this creates a much more intense contraction in the "shelf" area of the hip.

- The Lean Back: Shifting your weight slightly back onto your hands targets the fibers more toward the bottom of the hip complex.

- The Upright Hold: This is your baseline. It's great for posture, but it's the least "targeted" of the three.

Mixing these three positions within a single "drop set" is a brutal way to ensure total fiber recruitment. You might do 10 reps leaning forward, 10 upright, and 10 leaning back. By the end, your hips will feel like they’re made of molten lava.

Stop Calling It a "Girl Exercise"

There is a weird, lingering stigma in some old-school bodybuilding circles that hip abduction work is just for "toning" or for women looking to build a "booty." This is nonsense.

Look at any high-level powerlifter. Look at the guys squatting 800 pounds. They are almost certainly doing some form of lateral hip work. Why? Because the glute medius is what prevents the "knee cave" (medial collapse) under heavy loads. If those lateral stabilizers fail, the ACL is at risk, and the power transfer from the floor through the hips is compromised.

For athletes in sports like soccer or basketball, the band seated hip abduction is a literal insurance policy for the knees. Every time you cut, change direction, or land from a jump, your abductors are what keep your femur aligned.

Common Mistakes That Kill Your Progress

It’s easy to do this move poorly. The most frequent sin is "pumping." People move so fast that they’re using the elastic snap-back of the band to help them start the next rep.

- The Bounce: If the band is pulling your knees back together quickly, you’re missing 50% of the exercise. The eccentric (the way back in) should be slow and controlled.

- The Grip: Don't white-knuckle the bench. If you’re gripping the seat so hard your forearms are veining out, you’re likely over-bracing and losing focus on the hips.

- Ankle Rolling: Your feet should stay relatively flat, or you should rotate on the outer edge of the foot. Don't let your ankles do the work that your hips are supposed to do.

Variations and Equipment Choices

Not all bands are created equal. You have the thin latex "mini-bands" and the thick fabric "booty bands."

🔗 Read more: Mayo Clinic: What Most People Get Wrong About the Best Hospital in the World

The latex ones are notorious for rolling up your leg and snapping, which is basically a low-grade form of torture. They also lose their elasticity over time. Fabric bands are generally superior for band seated hip abduction because they stay in place and provide a more "smooth" resistance curve.

If you don't have a band? You can use a cable machine by sitting on a box and putting the cuff around your knee, though it's clunky. You can even use a partner providing manual resistance. But honestly, a $10 fabric loop band is the gold standard here.

The Science of Hip Stability

A 2020 study published in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine looked at hip abductor strength and its correlation with lower limb injuries. The findings were clear: individuals with higher hip abduction strength showed significantly better control of their center of mass during single-leg tasks.

While the seated abduction is an isolation move, it carries over into "functional" life by teaching the brain how to fire those muscles. It’s about neuromuscular efficiency. You’re telling your nervous system, "Hey, these muscles exist. Use them."

How to Program This Into Your Routine

Don't just do three sets of ten and go home. That won't do much for a muscle group as stubborn as the lateral glutes.

Try the "100-Rep Finisher." Use a light-to-moderate band. Perform the band seated hip abduction for 100 total reps, resting only when the burning becomes unbearable.

Alternatively, use it as a "primer" before you squat. Do 2 sets of 20 reps to wake the hips up. When you get under the barbell, you’ll find that "finding your glutes" is much easier because they’re already slightly fatigued and "awake."

💡 You might also like: Jackson General Hospital of Jackson TN: The Truth About Navigating West Tennessee’s Medical Hub

Real-World Application: Beyond the Gym

If you work a desk job, your abductors are likely in a weakened, lengthened state for 8 hours a day. This leads to that "tight" hip feeling I mentioned earlier. Ironically, the solution isn't always more stretching. It's often more strengthening.

Keeping a resistance band in your desk drawer and doing two minutes of seated abductions every few hours can genuinely alleviate lower back pain caused by postural collapse. It’s a low-sweat, high-reward habit.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Workout

To get the most out of the band seated hip abduction, follow this specific protocol during your next session:

- Select a fabric band with a resistance level that allows you to move your knees at least 6-8 inches apart.

- Sit at the very edge of the bench. Do not lean against a backrest.

- Place the band two inches above your kneecaps. Any higher and it loses leverage; any lower and it puts weird pressure on the joint.

- Perform 15 reps leaning forward at a 45-degree angle.

- Immediately perform 15 reps sitting tall, focusing on a 2-second hold at the widest point.

- Finish with 15 "pulses" in the outer one-third of the range of motion.

- Repeat this for 4 rounds. If you do this correctly, you won't just "feel" your glutes; you'll have a better understanding of how your hips control your entire lower body. The band seated hip abduction isn't a flashy move, and it won't win you any weightlifting competitions on its own. But it provides the structural integrity that allows you to be strong, mobile, and injury-free for the long haul.

Focus on the quality of the squeeze. Slow down the tempo. Stop worrying about using the heaviest band in the gym and start worrying about whether your glute medius is actually doing the work. Consistency with this small movement pays massive dividends in your "big" lifts.

Once you master the seated version, you can graduate to standing lateral walks or "monster walks," but for pure isolation and fixing imbalances, the seated version remains king. Keep your chest up, keep the tension constant, and embrace the burn. It’s a sign that you’re finally waking up the muscles that modern life has tried to put to sleep.

Next Steps for Implementation:

Check your squat footage. If your knees are dipping inward as you come "out of the hole," increase your seated hip abduction frequency to three times per week. Prioritize the 2-second isometric hold at the peak of the movement to build maximum neurological drive to the glute medius. Don't wait for hip pain to start—strengthen the stabilizers now to prevent the collapse later.