You’ve heard the hits. "Fortunate Son," "Bad Moon Rising," "Proud Mary"—they are the DNA of American rock. But the story of the band members of ccr isn’t just a highlights reel of Woodstock and gold records. Honestly, it’s a bit of a tragedy. Imagine being the biggest band in the world—literally outselling the Beatles in 1969—and then watching it all vanish because you couldn't stand to be in the same room as your own brother.

Most people think Creedence Clearwater Revival came from the bayous of Louisiana. They didn't. They were kids from El Cerrito, California.

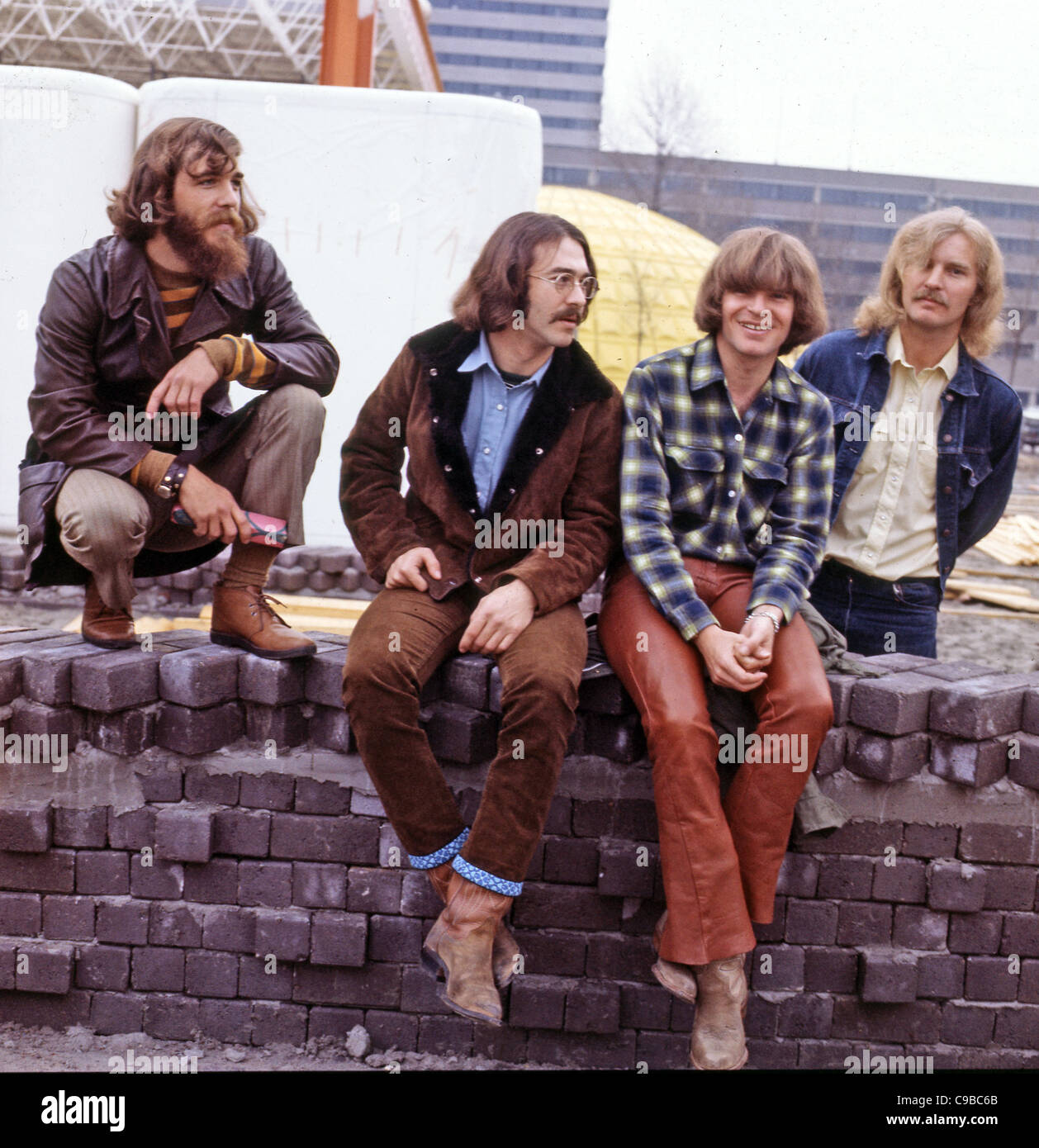

John Fogerty, Tom Fogerty, Stu Cook, and Doug Clifford weren't just colleagues; they were friends who had been playing together since junior high in the late 1950s. They went through the trenches. They were The Blue Velvets. They were The Golliwogs. They wore weird suits and played garage rock for years before the "Creedence" magic finally clicked.

The Core Four: Who Really Did What?

When we talk about the band members of ccr, we’re talking about a very specific chemistry that was incredibly lopsided. By the time they hit it big in 1968, the roles were set in stone.

- John Fogerty: He was the engine. Lead vocals, lead guitar, lead songwriter, producer, and manager. If you hear a CCR song, you’re hearing John’s vision.

- Tom Fogerty: John’s older brother. He played rhythm guitar. In the early days, Tom was actually the lead singer, but he stepped back when it became clear that John had "the sound."

- Stu Cook: The bassist. He actually started on piano before switching to bass to fill out the rhythm section.

- Doug "Cosmo" Clifford: The drummer. He and Stu were the "rhythm section" that provided that relentless, chugging "chooglin" beat.

It worked. For about three years, it worked better than almost any other band in history. Between 1968 and 1971, they released seven studio albums. That is an insane pace. But that pace came at a cost. John Fogerty was a perfectionist, often described as a dictator in the studio. He didn't want "creative input." He wanted the others to play the parts he wrote, exactly how he wrote them.

📖 Related: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Why the Band Members of CCR Started Fighting

Tension is a hell of a drug. By 1970, Tom Fogerty had enough. Imagine being the older brother and having your younger brother tell you exactly how to strum every chord. Tom quit in early 1971. He just wanted to be a musician again, not a session player for his sibling.

The band continued as a trio, but the vibes were rancid.

Stu and Doug wanted more say. They were tired of being "the backup band." In what John Fogerty later described as a moment of "if that's what you want, fine" spite, he gave them exactly what they asked for on their final album, Mardi Gras (1972). He told them they had to write and sing their own songs.

The result? Rolling Stone called it "the worst album ever made by a major rock band."

👉 See also: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

It was a disaster. The "democracy" killed the band. Shortly after, they called it quits. But the breakup was just the beginning of the real mess.

The Lawsuits That Never Ended

If you think modern band breakups are messy, the band members of ccr take the trophy. John Fogerty spent decades in legal warfare. Not just with his bandmates, but with Saul Zaentz, the head of Fantasy Records.

Zaentz owned the rights to the CCR songs. The contract the band signed was notoriously terrible—basically a "slave contract" in John's eyes. It got so bad that Zaentz actually sued John Fogerty for "plagiarizing himself." He claimed John’s solo song "The Old Man Down the Road" sounded too much like the CCR song "Run Through the Jungle."

John had to go to court with a guitar and prove he wasn't stealing from himself. He won, but the bitterness remained.

✨ Don't miss: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Life After Creedence

Tom Fogerty moved to Arizona and released several solo albums, but he never saw the success of the CCR days. Tragically, he died in 1990 from complications of AIDS, contracted via an unscreened blood transfusion. He and John never fully reconciled. That’s a heavy burden to carry.

Stu Cook and Doug Clifford eventually formed "Creedence Clearwater Revisited" in 1995. They just wanted to play the hits for the fans. John sued them over the name, of course. They eventually reached a settlement, and "Revisited" toured for 25 years before retiring in 2020.

What We Can Learn From the CCR Story

The legacy of the band members of ccr is a masterclass in the "creative genius vs. group harmony" struggle. John Fogerty was the reason they were great, but he was also the reason they couldn't last.

Next Steps for CCR Fans:

- Listen to the "Pre-Creedence" tracks: Search for The Golliwogs on streaming platforms. It’s wild to hear how much they struggled to find their identity before 1968.

- Watch the 1970 Royal Albert Hall concert: It was finally released in full recently. You can see the raw, locked-in power of the original four members before the wheels fell off.

- Check out John Fogerty’s memoir, Fortunate Son: It’s his side of the story, and it’s incredibly candid about his anger toward the other members and the record label.

The music is timeless, even if the friendships weren't. You can still hear the "chooglin" beat today in every dive bar and on every classic rock station, proving that even if the men couldn't stay together, the sound they made was indestructible.

Actionable Insight: If you're a musician or in a creative partnership, the CCR story is a reminder that defining roles and ownership before the money starts rolling in is the only way to save the relationship. Clear contracts and honest communication are less "rock and roll," but they keep the band together.