Robert Zemeckis didn't even want to make a sequel. That’s the big secret. When the credits rolled on the original film in 1985, that flying DeLorean was basically just a gag, a final "punchline" to send the audience home happy. But then the movie became a cultural supernova. Suddenly, Universal Pictures was banging on the door, and Zemeckis and Bob Gale were stuck. They had literally flown their characters into a future they hadn't actually built yet. Back to the Future II was born out of that corner they'd painted themselves into, and honestly, it’s probably the most ambitious, chaotic, and fascinating sequel in Hollywood history.

It’s dark. It’s messy. It’s a movie that spends half its runtime inside the events of its own predecessor. Most sequels just try to do the first movie again, but bigger. This one? It decided to play 4D chess with the timeline.

The 2015 Problem and Why They Got So Much Wrong

People always joke about the lack of flying cars. Where are they? We were promised skyways! Bob Gale has been on record dozens of times saying they knew flying cars wouldn’t be a thing by 2015. They put them in because a "future" movie without them feels like a letdown. It was an aesthetic choice, not a prediction. But looking back at the 2015 of Back to the Future II, the stuff they missed is way more interesting than the stuff they hit.

Think about the communication. Marty McFly Jr. sits at a dinner table wearing high-tech goggles, ignoring his family. Sound familiar? That’s basically everyone at a dinner table in 2024 with an iPhone or an Apple Vision Pro. They nailed the "social isolation through technology" vibe perfectly. But then you look at the walls. Fax machines. They thought the pinnacle of 2015 communication would be faxing people in every room of the house. They missed the internet. Almost everyone in the late 80s did. They envisioned a world that was still analog at its heart, just with more neon and hydraulics.

Then there’s the fashion. Double ties? Turning your pockets inside out? It’s absurd. But if you look at modern streetwear or some of the stuff hitting runways in Paris lately, the movie’s costume designer, Joanna Johnston, wasn’t that far off on the vibe. It’s all about performative, weird layers.

The Biff Tannen Paradox

If you want to talk about the legacy of this film, you have to talk about 1985A. That’s the "alternate" timeline where Biff Tannen is a billionaire mogul who turned Hill Valley into a gambling wasteland. For years, fans speculated on who Biff was based on. In 2016, Bob Gale finally confirmed it to The Daily Beast: Biff Tannen was a direct parody of Donald Trump.

The physical similarities are there—the tower, the hair, the ego—but the narrative function is what matters. The movie suggests that a single piece of information, a sports almanac from the future, can destroy the fabric of a democracy. It’s a pretty heavy concept for a movie that features a teenager on a pink Mattel hoverboard. This middle act of the film is surprisingly gritty. It’s where the "fun" adventure of the first movie dies, replaced by a dystopian nightmare that feels way more like Blade Runner than a Spielberg-produced family flick.

✨ Don't miss: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

Why the Second Act is a Technical Miracle

The "re-visiting 1955" sequence is where the movie goes from a standard sequel to a technical masterpiece. Remember, this was 1989. Computer-generated imagery (CGI) was in its infancy. Jurassic Park was still years away. To get Michael J. Fox to interact with himself, the crew had to use something called the VistaGlide.

The VistaGlide System

This was a motion-control camera system that allowed the camera to move in a programmed sequence, then repeat that exact movement while the actors moved to different positions in the frame. If the camera nudged even a millimeter out of place, the "split screen" would break.

It was tedious. Actors had to play against nothing. Michael J. Fox had to play three different versions of himself in one scene—Marty, Marty Jr., and Marlene—and he had to do it while hitting marks with mathematical precision. When you see old Marty handing a bowl of fruit to young Marty, that’s not a digital trick. It’s a perfectly timed physical hand-off combined with some of the most clever editing of the era.

- The Diner Scene: Michael J. Fox played three characters.

- The Lighting: Had to remain identical over days of shooting for a single scene.

- The Sound: Dialogue had to be recorded separately and layered perfectly.

The Hoverboard Obsession

Nothing from this movie has haunted the public imagination more than the hoverboard. After the film came out, Robert Zemeckis did a "behind-the-scenes" interview where he jokingly claimed that hoverboards were real but were being kept off the market by "parents' groups" who thought they were too dangerous.

People actually believed him.

Mattel was flooded with calls. For a solid decade, kids were convinced that the technology existed and was just being suppressed. In reality, it was all wires and movie magic. The actors were suspended from cranes, and the boards were bolted to their feet. Even today, company after company tries to build a "real" hoverboard using magnets (like the Hendo Hover) or liquid nitrogen-cooled superconductors (Lexus). None of them actually work like the movie version. We're still chasing that dream.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

Complex Timelines and Why We Love the Mess

Back to the Future II is the reason we have "timeline" headaches in movies today. It introduced the general public to the idea of a branching reality. If you change the past, you don't just change your own future; you create a whole new universe.

Doc Brown’s chalkboard scene is the most important scene in the franchise. It’s the "infodump" that explains how time travel works in this universe. Without it, the audience would have been hopelessly lost by the time Marty goes back to the 1955 dance to steal the almanac while his other self is on stage playing "Johnny B. Goode."

It’s a daring piece of filmmaking. It trusts the audience to remember the first movie beat-for-beat. If you haven't seen the 1985 original, the last 45 minutes of the sequel make zero sense. That was a huge risk at the time. Sequels were supposed to be standalone. Zemeckis bet on the fans' intelligence, and it paid off.

The Real Cost of the Movie

It wasn't all fun and flying cars. The production was grueling. They filmed Part II and Part III back-to-back, which was almost unheard of at the time. Michael J. Fox was exhausted, often filming the movies during the day and his sitcom, Family Ties, at night.

There was also the Crispin Glover situation. Glover, who played George McFly in the first film, didn't return for the sequel. Instead of recasting him normally, the production used a prosthetic mask on actor Jeffrey Weissman to make him look like Glover, and they used old footage of Glover from the first movie. This led to a landmark lawsuit regarding "personality rights." Glover won. Because of this movie, there are now strict rules in Hollywood about using an actor's likeness without their permission.

Actionable Takeaways for Movie Buffs

If you’re planning a rewatch, or if you’re a filmmaker looking to understand why this movie still works, keep these things in mind:

💡 You might also like: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

Watch the Background

The detail in the 2015 scenes is insane. Look at the movie posters (Jaws 19 directed by Max Spielberg), the newspaper headlines (mentioning a visit from "Queen Diana"), and the "Antique" shop windows containing 1980s junk like original Nintendo Dust-Busters. It’s a masterclass in world-building.

Study the Editing

Pay attention to the transitions when Marty is in 1955 for the second time. The way the editors (Arthur Schmidt and Harry Keramidas) weave the new footage with the 1985 footage is seamless. It’s a textbook on how to handle "parallel" narratives.

Notice the Tonal Shift

See how the movie moves from a bright, colorful comedy in 2015 to a dark noir in 1985A, and then to a heist movie back in 1955. It shouldn't work. It’s three different genres in one film.

Evaluate the Prop Design

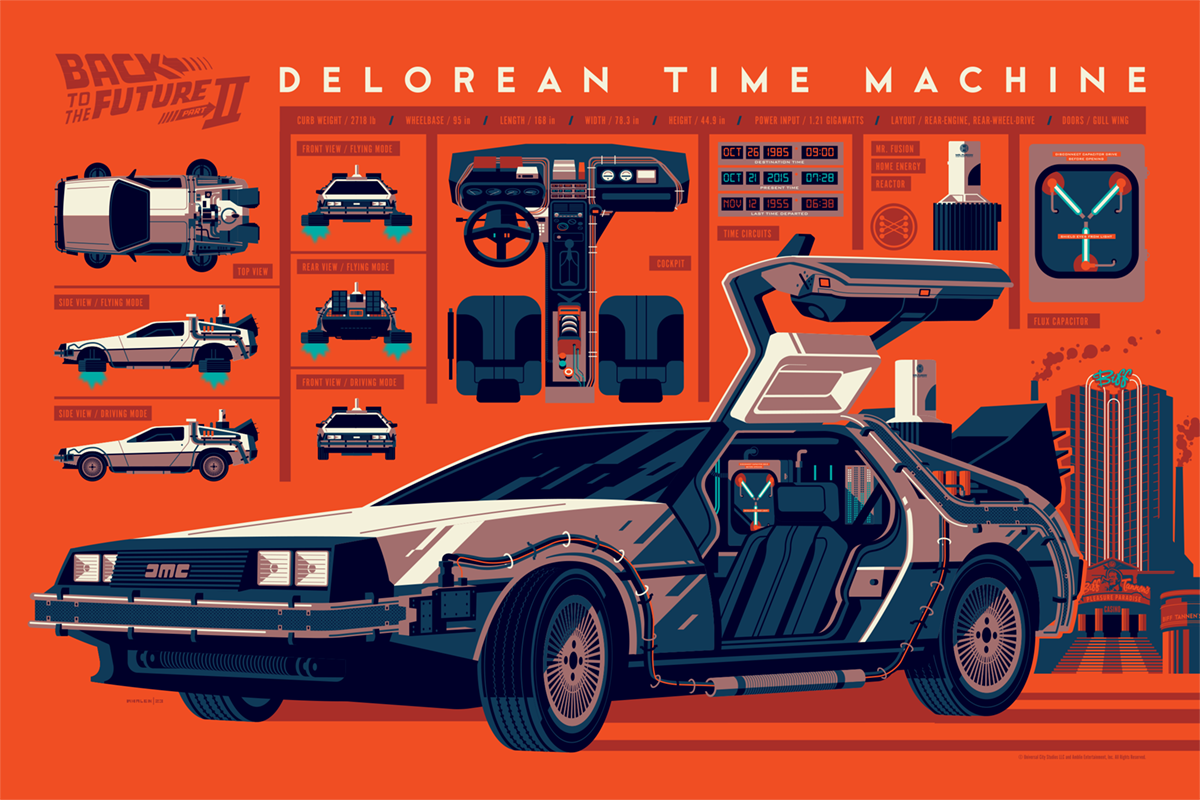

The "Mr. Fusion" on the back of the DeLorean was actually a Krups coffee grinder. The "Pit Bull" hoverboard was just a piece of painted wood. Great sci-fi doesn't need billion-dollar tech; it needs a great silhouette and a believable texture.

To really appreciate what Zemeckis did, you have to stop looking at the flying cars and start looking at the structure. It’s a movie that eats itself, celebrates itself, and then warns you about the dangers of knowing too much about your own life. It’s the rare sequel that makes the original movie better by adding stakes we didn't know existed.

Next Steps for the Ultimate Experience:

- Compare the 1955 scenes: Watch the "Enchantment Under the Sea" dance in the original movie, then immediately watch the version in Part II. Note where the camera is placed—Zemeckis had to recreate the sets perfectly to match the angles.

- Track the Almanac: Follow the physical path of the Gray’s Sports Almanac throughout the film. It changes hands seven times. Map out each transition to see how the plot actually moves.

- Research the "Cubs" Prediction: Look into the 2016 World Series. The movie predicted the Chicago Cubs would win in 2015. They were only off by one year. Consider how that coincidence fueled the movie's "prophetic" reputation for decades.