It starts with that snare hit. It’s dry, crisp, and sounds like it was recorded in a basement in 1964, even though it actually came out of a studio in New York or London in the mid-2000s. When you hear the opening bars of Back to Black by Amy Winehouse, you aren't just listening to a song. You're basically stepping into a time machine that’s malfunctioning in the best way possible. It’s heavy. It’s dark. Honestly, it’s probably the most honest depiction of a nervous breakdown ever put to tape.

Most people remember the beehive hair and the thick eyeliner, but the music was what actually mattered. Mark Ronson and Salaam Remi weren't just producing tracks; they were building a fortress for Amy’s voice to live in. That voice—raspy, defiant, and soaked in Gin—turned a breakup album into a cultural monument. It’s weird to think about how much the landscape of pop music changed because of this one record. Before Amy, the charts were dominated by polished, plastic R&B and post-grunge leftovers. Then she showed up with a 60s girl-group obsession and a vocabulary that would make a sailor blush.

The title track itself is a masterpiece of misery. You’ve got those rolling piano chords that sound like a funeral march. It’s not a "get over him" anthem. It’s a "I’m going to sit in this darkness until it swallows me whole" anthem. That’s why it stuck. People don't always want to be told they’ll find someone better. Sometimes they just want to hear someone else admit that they’ve gone back to black, too.

The messy reality of the Back to Black recording sessions

If you think this album was the result of a smooth, corporate plan, you’ve got it all wrong. It was chaotic. Amy walked into the studio with a heart that had been put through a paper shredder, mostly thanks to her turbulent relationship with Blake Fielder-Civil.

She met Mark Ronson in March 2006. He’s gone on record saying she was incredibly blunt. She played him The Shangri-Las and The Ronettes. She wanted that Wall of Sound. Ronson took those influences and mixed them with a hip-hop sensibility he’d learned in New York. The result was something that felt vintage but hit with the sub-bass of a modern record. While "Rehab" was the big radio hit, the soul of the project lived in the darker corners of the tracklist.

Take "Love Is a Losing Game." It’s barely two and a half minutes long. It’s just a few chords and a devastating vocal. Prince famously loved that song, and for good reason. It’s a perfect composition. There’s no fluff. During the sessions, Amy was often writing lyrics on the fly, pulling from her journals and her immediate, raw pain. She wasn't trying to be a star; she was trying to survive her own head.

👉 See also: Charlie Charlie Are You Here: Why the Viral Demon Myth Still Creeps Us Out

Why the Dap-Kings were the secret weapon

You can't talk about the sound of Back to Black by Amy Winehouse without mentioning the Dap-Kings. This was Sharon Jones's backing band, a group of Brooklyn-based musicians who lived and breathed old-school soul. Ronson hired them to provide the instrumentation, and they brought a grit that digital plugins just can't mimic.

- The brass isn't synthesized; it's loud, brassy, and occasionally slightly out of tune in a way that feels human.

- The drums were recorded with minimal microphones to get that compressed, vintage "thump."

- Everything was played live in the room, which is why the record breathes.

When you listen to the title track, those bells and the baritone sax create a sense of impending doom. It’s theatrical. It’s "Leader of the Pack" if the leader of the pack never came back and the girl stayed at the graveyard forever.

Breaking down the lyrics: More than just "Rehab"

"You go back to her and I go back to black." It’s such a simple line, but it carries the weight of a lead pipe. Amy wasn't just talking about a person; she was talking about a state of mind. She was talking about addiction, depression, and the literal blackness of a life without a fixed point.

The lyrics across the album are surprisingly funny, too, which people often overlook. In "Me & Mr Jones," she’s annoyed about missing a Slick Rick gig. In "You Know I'm No Good," she’s cheating and then sniffing her boyfriend's tan like a "block of cheese." It’s weird, specific, and incredibly British. That specificity is what makes it universal. She wasn't singing about "the club" or "the dance floor." She was singing about her kitchen, her "fella," and her "Ray-Bans."

The Grammy sweep and the shift in pop history

In 2008, the Grammys were basically the Amy Winehouse show. She won five awards in one night. Because of her visa issues, she had to perform via satellite from London. When she won Record of the Year, the look of genuine shock on her face was one of the few authentic moments in award show history.

✨ Don't miss: Cast of Troubled Youth Television Show: Where They Are in 2026

But the real impact wasn't the trophies. It was the "Amy Effect." Look at the artists who came immediately after her. Adele has explicitly stated that Amy paved the way for her. Duffy, Florence + The Machine, Lana Del Rey—they all owe a massive debt to the door Amy kicked down. She made it okay for female pop stars to be "difficult," to have deep voices, and to write about things other than sunshine and rainbows.

The dark side of the success

We have to be honest: the success of this album fed the paparazzi machine that eventually contributed to her downfall. The more she sang about her pain, the more people wanted to see it in real life. It’s a grim irony. The very thing that made her an icon—her vulnerability—was what the media exploited until there was nothing left.

Even so, the music survives the tragedy. If you listen to "Wake Up Alone," you hear a woman who is completely in control of her craft, even if her life was spinning out. The phrasing is jazz-level perfection. She slides behind the beat, pulls it forward, and plays with the melody like she’s Sarah Vaughan in a denim mini-skirt.

How to listen to Back to Black today

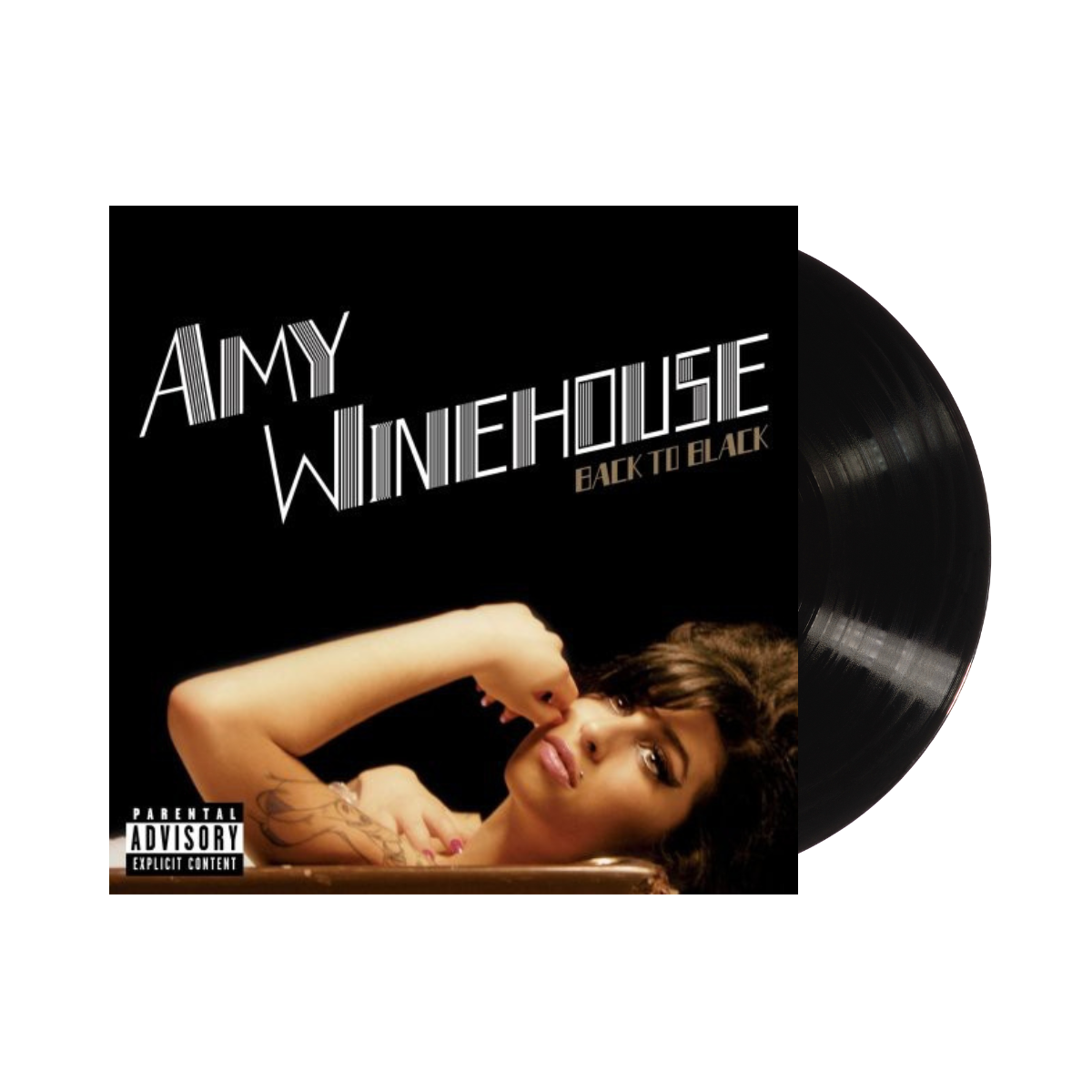

If you’re revisiting the album or hearing it for the first time, don't just stream it on crappy phone speakers. This is a record that demands some air.

- Get it on vinyl. Seriously. The analog warmth fits the 60s production style perfectly.

- Listen to the B-sides. Tracks like "Valerie" (the Zutons cover) and "To Know Him Is To Love Him" show a different, lighter side of her vocal ability.

- Watch the 2015 documentary 'Amy'. It provides the necessary context for the lyrics, showing the home videos of her as a jazz-obsessed kid before the chaos started.

Actionable Insights: Learning from Amy's Artistry

Amy Winehouse didn't follow a trend; she became the trend by looking backward. For anyone creating anything today, there are a few real takeaways from the Back to Black by Amy Winehouse era.

🔗 Read more: Cast of Buddy 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

First, authenticity isn't a marketing term. People felt her pain because it was real. You can't fake the kind of soul she put into "Wake Up Alone." If you’re writing or creating, lean into the stuff that makes you uncomfortable. That’s usually where the good stuff lives.

Second, collaboration is everything. Amy had the songs, but Mark Ronson and Salaam Remi had the "sonic clothes" to dress them in. Find people who understand your vision but have the technical skills to elevate it.

Finally, know your history. Amy was a student of jazz and 60s soul. She wasn't just copying them; she was synthesizing them into something new. To break the rules of your craft, you have to know them inside out first.

Go back and listen to the title track one more time. Focus on the way she sings the word "black" at the very end. It’s not a note; it’s a sigh. That’s the difference between a singer and an artist.

Next Steps for the Music Enthusiast:

- Audit your playlist: Compare the production of Back to Black to modern "retro-soul" artists like Leon Bridges or Celeste to see how the influence persists.

- Deep dive the samples: Research the 1960s girl groups Amy loved, specifically The Shangri-Las' "Remember (Walking in the Sand)," to hear exactly where the DNA of this album comes from.

- Explore the London Jazz Scene: Look into the South London jazz circuit where Amy got her start to understand the technical foundation of her unique vocal phrasing.