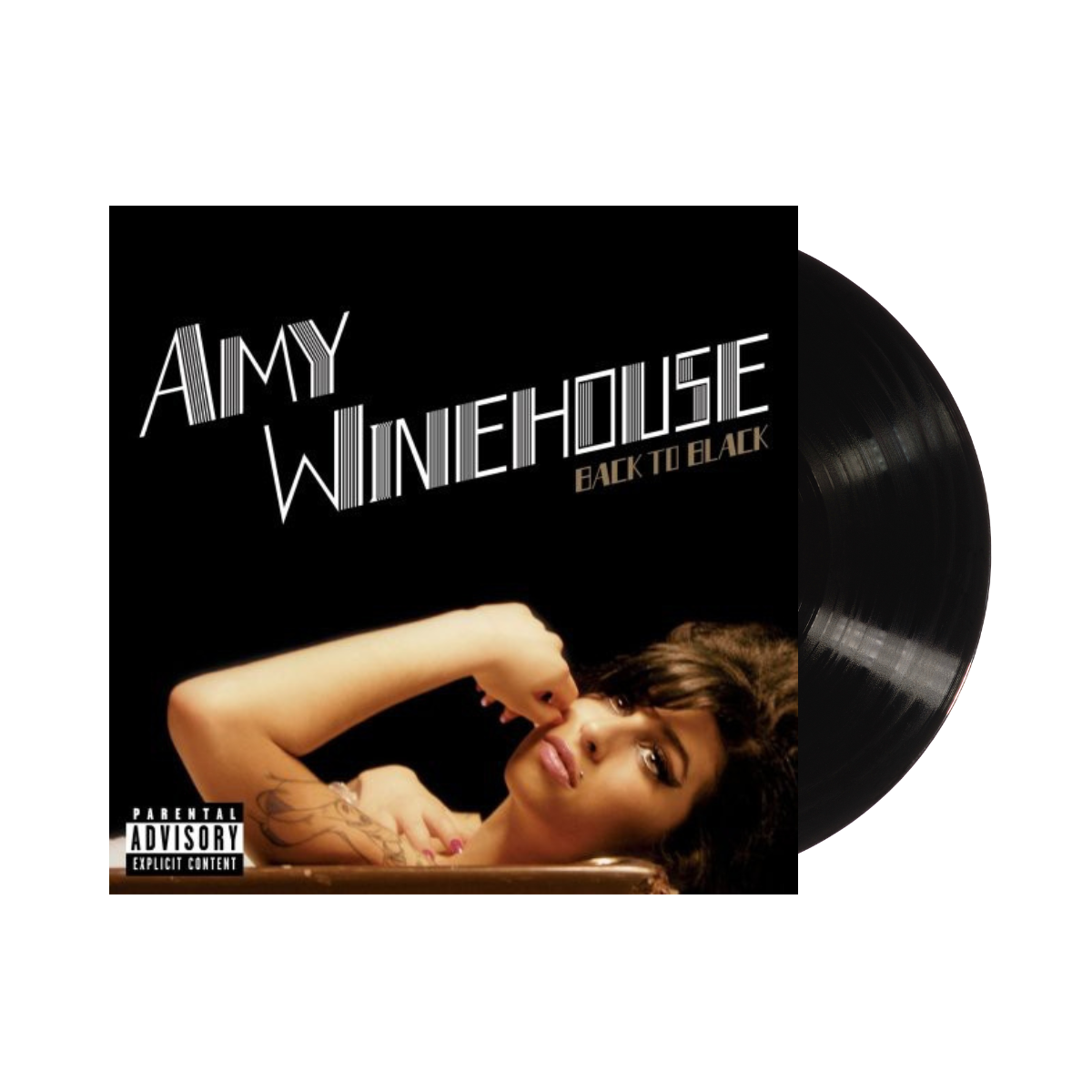

You know that feeling when a song hits so hard it feels like a physical bruise? That was the entire vibe when Back to Black Amy Winehouse dropped. It wasn't just an album. It was a funeral for a relationship that wasn't even technically dead yet.

People love to talk about the beehive, the eyeliner, and the tabloid chaos. Honestly, it's exhausting. We get so caught up in the "train wreck" narrative that we forget the actual music was a feat of engineering and raw, bloody-knuckled talent.

The Myth of the "Accidental" Hit

Most people think Back to Black was just Amy pouring her heart out into a microphone while Mark Ronson happened to be standing there with a recorder.

Not true. Not even close.

Amy was a perfectionist. A total nerd about sound. She didn't just stumble into that 60s soul sound; she hunted it down. She used to burn rough mixes onto CDs and play them in her dad’s taxi just to see how they sounded in a real car on a noisy London street. If it didn’t pass the "taxi test," it wasn’t finished.

The album was a split effort between two very different worlds. You had Salaam Remi in Miami and Mark Ronson in New York. Salaam brought the jazz and the hip-hop weight. Ronson brought the Dap-Kings and that dusty, analog Wall of Sound.

It worked because she was blunt. Ronson once mentioned that he loved working with her because she’d tell him straight up if his ideas were trash. No ego. Just the song.

Why Back to Black Amy Winehouse Still Hurts

The title track is a masterclass in misery. We’ve all heard it, but have you listened to it lately?

"We only said goodbye with words / I died a hundred times."

Ronson actually wanted to change that line. He thought it didn't rhyme right or needed more polish. Amy shut him down. She knew that the clunkiness of the line was where the truth lived.

The phrase "back to black" wasn't just a catchy title. For Amy, it was literal. It was the "black" of depression, the "black" of the drinks she was using to drown out the fact that Blake Fielder-Civil had gone back to his ex-girlfriend.

She wasn't just sad. She was mourning a version of herself that existed when they were together.

💡 You might also like: The Legendary Hero Is Dead Characters and Why They Are So Weirdly Written

The Production Secrets Nobody Mentions

Everyone talks about the retro feel, but the technical side was wild.

- The One-Mic Wonder: Most of the drums on the Ronson tracks were recorded with a single microphone. One. That’s why it sounds so boxy and authentic.

- Tape Only: Gabriel Roth at Daptone Records was a stickler. They used actual tape machines, not just plugins that "look" like tape.

- The Spill: In modern recording, you want "isolation"—every instrument in its own bubble. For Back to Black, they threw everyone in one room. The drums bled into the piano mic. The bass leaked into the vocal booth. That "leakage" is exactly what makes the record feel alive and warm.

The Grammy Night That Changed Everything

February 2008. Amy couldn’t even get a visa to be there in person because of her legal and substance issues. She performed via satellite from a small studio in London.

She won five Grammys that night.

When she won Record of the Year for "Rehab," she looked genuinely confused. Watch the footage again—she looks at her mom, looks at her band, and says, "This is for London because Camden Town is burning down!" (There was a massive fire in Camden that night).

She wasn't a "pop star." She was a girl from North London who happened to have a voice that sounded like it had been cured in tobacco and heartbreak for fifty years.

✨ Don't miss: TV Shows With Adrian Hough: Why He’s the Most Familiar Face You Can’t Quite Place

The Aftermath and the "Soul" Invasion

Before Back to Black Amy Winehouse, the charts were dominated by high-gloss R&B and synth-pop. Soul was a "niche" genre for older people.

Amy kicked the door down.

Without her, do we get Adele? Probably not. Adele herself said she picked up a guitar because of Amy. Do we get Duffy or Estelle? Unlikely. She made it okay for British singers to sound like they actually felt something again.

But there’s a dark side to that legacy. Following her death in 2011, the industry started looking for "the next Amy." We got a decade of singers over-singing and "chewing" their vowels to try and mimic her grit. But you can't fake it. You can't manufacture the kind of honesty that comes from "Love Is a Losing Game."

💡 You might also like: Where Can I See Beetlejuice Right Now: A Streamer's Guide to Both Movies

What to Do With This Legacy Today

If you really want to appreciate the work, stop reading the old tabloids. They don't matter anymore.

- Listen to the B-Sides: "Addicted" and "Valerie" (the Zutons cover) show her range beyond the heartbreak.

- Watch the 2015 "AMY" Documentary: It uses her own home movies to show the songwriter, not the caricature.

- Check out the Dap-Kings: Explore the band that gave the album its backbone. They are the unsung heroes of the 2000s soul revival.

Back to Black isn't a museum piece. It’s a living, breathing record of what happens when a generational talent decides to be completely, terrifyingly honest about her own destruction. It’s messy. It’s loud. It’s perfect.

To truly honor the artist, focus on the craft. Listen to the way she drags her voice behind the beat on "You Know I'm No Good." That’s where the genius lives—not in the headlines, but in the half-second delays and the "no, no, no" that the whole world sang along to, even when we should have been listening closer.