You probably think you know where "Away in a Manger" came from. Most people do. For decades, church hymnals and primary school teachers across the globe attributed the Away in a Manger lyrics to Martin Luther, the great German reformer. It makes sense, right? The song has that gentle, lullaby-like quality that feels like it could have been hummed by a 16th-century father to his children by a fireplace in Wittenberg.

Except Luther didn’t write it. Not even a single word.

The story behind this carol is actually a fascinating bit of 19th-century marketing, a touch of accidental deception, and a lot of musical evolution. It’s one of the most popular Christmas songs in the English-speaking world, yet its origins were shrouded in mystery for nearly a hundred years. If you've ever felt a little tug at your heartstrings hearing "no crying he makes," you’re part of a tradition that is much more American than it is German.

The "Luther’s Cradle Hymn" Myth

The whole idea that Martin Luther penned these words was basically a very successful PR campaign from the 1880s. In 1882, the lyrics appeared in a Lutheran Sunday School book in Philadelphia. The editors labeled it "Luther’s Cradle Hymn," claiming it was something Luther sang to his own kids. It was a sweet sentiment. People loved it.

The problem? No one can find this poem in any of Luther’s actual writings. Not in German, not in Latin, not anywhere.

Musicologist Richard Hill did a massive deep dive into this back in the 1940s. He looked at every possible source and concluded that the song is almost certainly American. It likely emerged around the 400th anniversary of Luther’s birth in 1883. It seems some clever folks in Pennsylvania wanted to celebrate the anniversary with a "newly discovered" song from the Reformer himself. It wasn't necessarily a malicious lie; it was more like "historical fiction" that everyone just started believing was true. Honestly, it’s kind of impressive how well it stuck.

🔗 Read more: Christmas Treat Bag Ideas That Actually Look Good (And Won't Break Your Budget)

Breaking Down the Away in a Manger Lyrics

Most of us know the first two verses by heart. The third one? Not so much. That’s because the third verse wasn't even part of the original publication.

The first two verses first appeared in Little Pilgrim’s Progress in 1884. They set the scene perfectly. You have the "little Lord Jesus" asleep on the hay, the stars looking down, and the cattle lowing. It’s a very static, peaceful image.

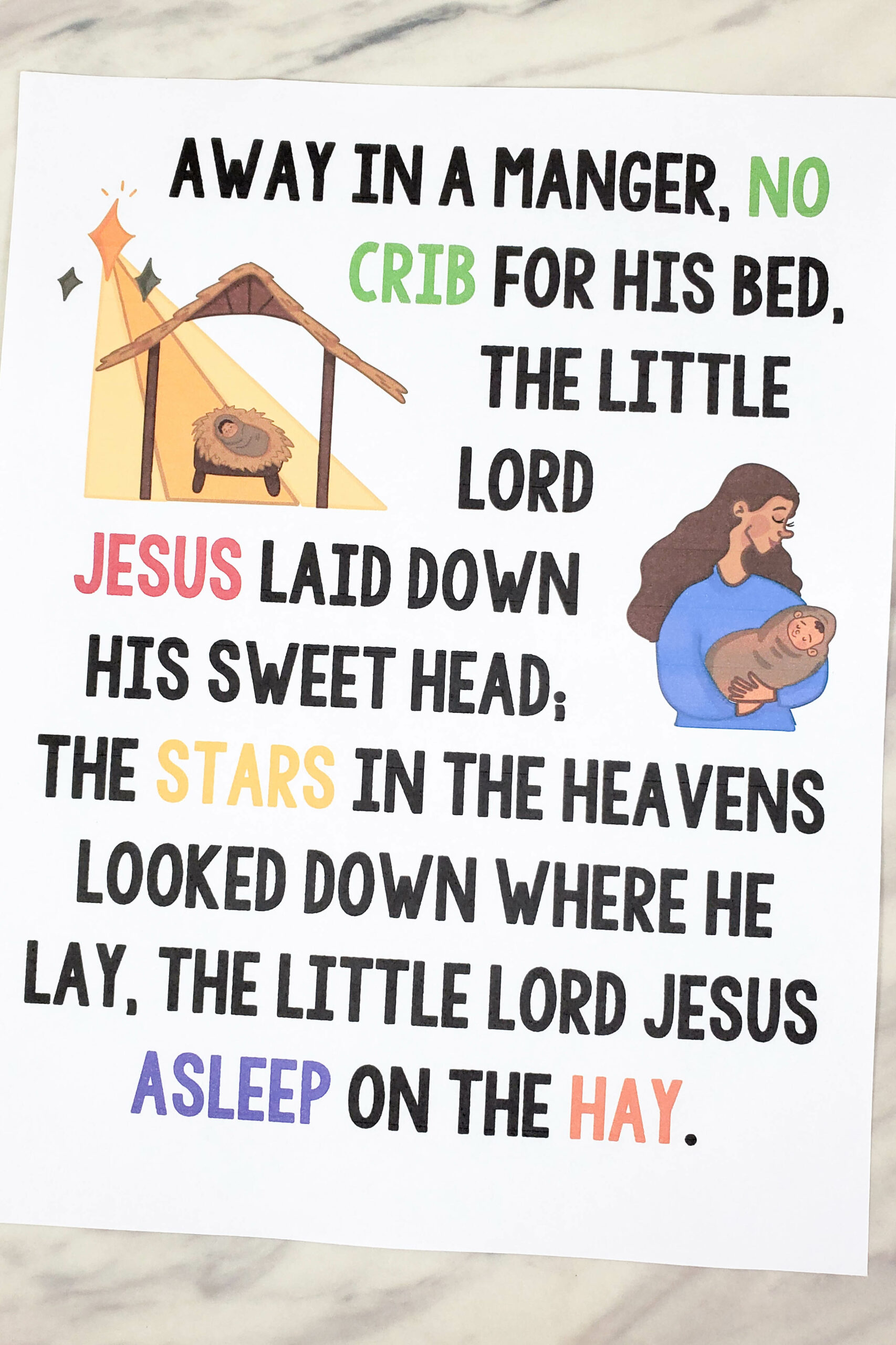

"Away in a manger, no crib for a bed,

The little Lord Jesus laid down his sweet head."

Then comes the second verse with the famous "no crying he makes" line. This specific phrase has actually caused a bit of a stir among theologians over the years. Some argue it suggests Jesus wasn't "fully human" because, well, babies cry. If he didn't cry, was he actually a human infant? It’s a bit of a heavy debate for a preschool Christmas pageant, but it shows how much weight we put on these simple lines.

The third verse, starting with "Be near me, Lord Jesus; I ask thee to stay," didn’t show up until 1892 in a book called Gabriel’s Vineyard Songs. It was likely written by John T. McFarland. He supposedly wrote it because he felt the song needed a more prayerful ending. It shifted the song from a historical description to a personal plea for guidance.

💡 You might also like: Charlie Gunn Lynnville Indiana: What Really Happened at the Family Restaurant

A Tale of Two Melodies

Depending on where you grew up, "Away in a Manger" sounds completely different.

In the United States, we mostly sing the version composed by James Ramsey Murray in 1887. It’s called "Mueller." It’s the one with the jumping, lilting melody that feels like a rocking cradle.

If you’re in the UK or parts of the Commonwealth, you’re probably singing "Cradle Song." This version was composed by William J. Kirkpatrick in 1895. It’s smoother, a bit more sophisticated, and arguably more "hymn-like."

There’s actually a third version by Jonathan E. Spilman called "Flow Gently, Sweet Afton" (originally for a Robert Burns poem) that sometimes gets used, but Murray and Kirkpatrick are the heavy hitters. It's rare for a song to have two distinct melodies that are both equally "correct" depending on your geography.

Why Do We Keep Singing It?

Let’s be real. The imagery is a little sanitized. Real stables are smelly, loud, and definitely not the kind of place you’d want to put a newborn. But the Away in a Manger lyrics aren’t trying to be a gritty documentary. They are a lullaby.

📖 Related: Charcoal Gas Smoker Combo: Why Most Backyard Cooks Struggle to Choose

The song works because it’s accessible. The vocabulary is simple. The rhymes are predictable. It’s usually the first song a child learns to sing in a choir. There is a profound psychological comfort in the idea of a "little Lord Jesus" who is safe and watched over by stars.

It also bridges the gap between the divine and the mundane. The cattle are just doing their thing—lowing, being cows—and right there in the middle of the farm life is something holy. It makes the Christmas story feel domestic and reachable.

Common Misconceptions and Fun Facts

- The "Cattle are Lowing" confusion: Many kids (and some adults) think "lowing" means they are lying down. Nope. Lowing is an old word for mooing. The cows are making noise, but Jesus is such a chill baby he doesn't wake up.

- The Anonymous Author: Since it wasn't Luther, who was it? We honestly don't know. It was likely an anonymous American songwriter, possibly from a German-Lutheran community in the Midwest or Pennsylvania, who wanted to write something that sounded like it could be from the Old Country.

- The Third Verse: John T. McFarland, the guy who likely wrote the third verse, was a prominent Methodist. This means the song is a weird, beautiful mix of Lutheran myth and Methodist additions.

Practical Ways to Use the Lyrics This Season

If you're planning a service or just want to appreciate the song more, keep the history in mind.

- Compare the Tunes: Try playing the Murray version and the Kirkpatrick version back-to-back. It’s a great way to show how melody changes the "emotional flavor" of a text.

- Focus on the Third Verse: Since it's the "forgotten" verse, try reading it as a standalone prayer. It’s surprisingly deep: "Bless all the dear children in thy tender care, and fit us for heaven to live with thee there."

- Teach the "Lowing" Part: If you have kids, explain what the words actually mean. It turns a rote memorization task into a vocabulary lesson.

The Away in a Manger lyrics might not be the ancient German relic we once thought they were, but that doesn't make them any less meaningful. They represent a specific moment in American religious history where we wanted to create something sweet, simple, and lasting. And 140 years later, it’s safe to say it worked.

To get the most out of your holiday music, look for hymnals that provide the "Mueller" and "Cradle Song" arrangements side-by-side to see the harmonic differences. You can also research the 1883 Luther celebrations in Pennsylvania to see just how deep the "Cradle Hymn" legend goes in local archives.