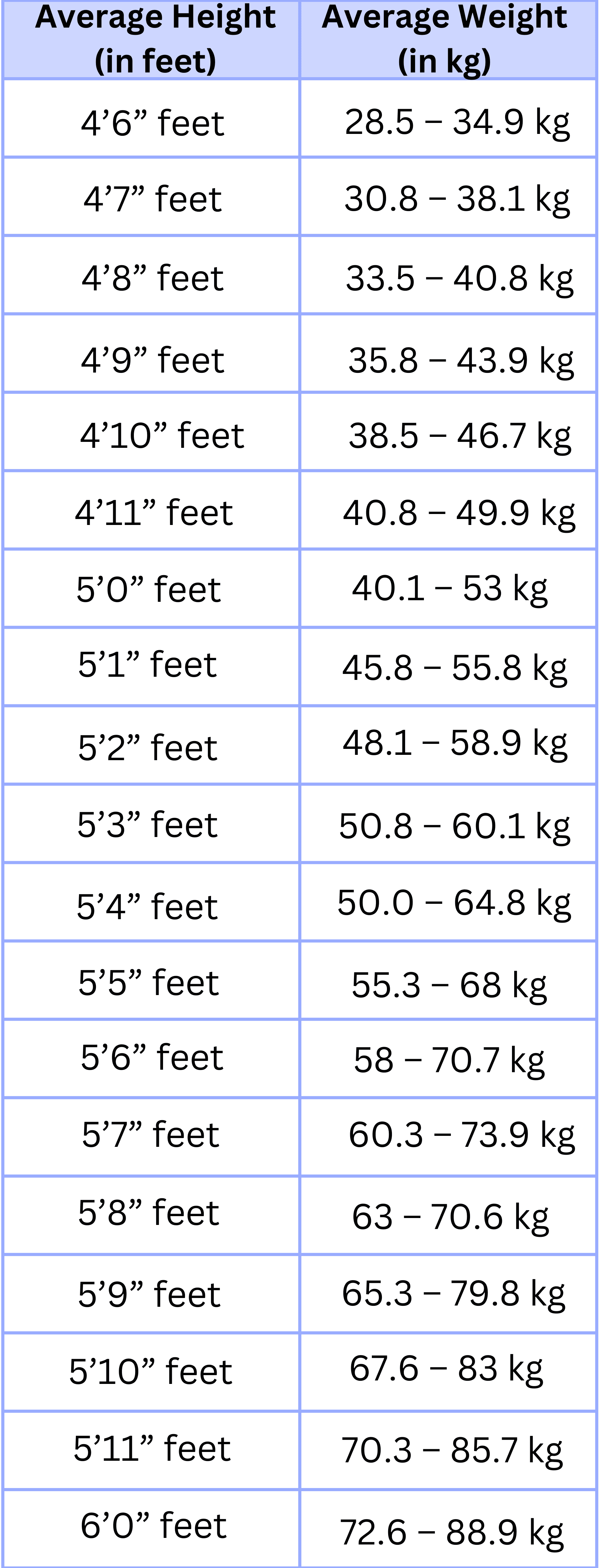

You’re standing in the doctor's office. You look at that laminated piece of paper taped to the wall—the average weight and height chart—and you start doing the math. Maybe you feel a pang of guilt. Or maybe you’re confused because you hit the "ideal" number but your jeans still don't fit right.

Most people treat these charts like a moral report card. They aren't. Honestly, they’re just data aggregates. They tell us what the middle of the bell curve looks like for a massive population, but they don't know a thing about your bone density, your muscle mass, or whether you just finished a heavy leg day and are holding five pounds of water weight. We need to stop looking at these charts as "goals" and start seeing them as the blunt instruments they actually are.

The Problem With the "Average" Label

When we talk about an average weight and height chart, we’re usually looking at data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the World Health Organization (WHO). For adults in the United States, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) does the heavy lifting. According to their most recent comprehensive reports, the average American man stands about 5 feet 9 inches tall and weighs around 199.8 pounds. For women, the average is roughly 5 feet 3.5 inches and 170.8 pounds.

Does that mean those are the "healthy" weights? Not necessarily.

There’s a massive gap between "average" and "optimal." If the average weight has been steadily climbing for decades—which it has—the "average" person might actually be at risk for metabolic issues. Conversely, a chart might tell a 6-foot-tall athlete they’re "overweight" because they have 40 pounds of functional muscle that the chart thinks is fat. The chart is a map, but you are the terrain.

How the NHANES Data Changes the Game

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is where this data actually comes from. It’s not just a guess. They actually bring people into mobile trailers and measure them. But here’s the kicker: these numbers change based on demographics. Age matters. Ethnicity matters. A 20-year-old and a 70-year-old might share a spot on an average weight and height chart, but their body compositions are worlds apart. Sarcopenia—the natural loss of muscle as we age—means that a 150-pound senior has a much higher body fat percentage than a 150-pound college student.

Why BMI is a Terrible Individual Metric

Most average weight and height charts are built on the back of Body Mass Index (BMI). We’ve been using BMI since Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian mathematician, invented it in the 1830s. He wasn't even a doctor. He was a statistician trying to define the "average man" for social physics.

$BMI = \frac{weight(kg)}{height(m)^2}$

It’s a simple formula. Too simple. It doesn’t account for where your fat is stored. Science has shown us repeatedly that visceral fat—the stuff packed around your organs in your abdomen—is way more dangerous than subcutaneous fat on your hips or arms. You could have a "normal" BMI on an average weight and height chart but still have "skinny fat" syndrome (normal weight obesity), which carries many of the same risks as being clinically obese.

The Muscle Factor

Think about a professional rugby player. Or a CrossFit athlete. They are often 5'10" and 220 pounds. On any standard chart, they’re labeled "Obese Class I." It’s ridiculous. Muscle is roughly 15% denser than fat. If you’re lifting weights and getting leaner, your scale might not move, or it might even go up. If you're following a chart blindly, you might think you're failing when you're actually succeeding.

Developmental Charts: Kids Are Different

Now, if you’re a parent looking at an average weight and height chart for a child, the rules change. We use percentiles here. If your pediatrician says your daughter is in the 50th percentile, it just means she’s right in the middle. If she’s in the 5th or the 95th, it’s not automatically a "red flag."

What doctors actually look for is the curve.

Growth is supposed to be consistent. If a child has been in the 75th percentile for three years and suddenly drops to the 10th, that’s when you worry. The specific number matters less than the trend line. We also have to consider the "Mid-Parental Height" calculation. Basically, genetics sets the ceiling.

For boys: $((Father's Height + Mother's Height + 13 cm) / 2)$

For girls: $((Father's Height + Mother's Height - 13 cm) / 2)$

This gives a much better picture of where a kid "should" be than a generic chart ever could.

Historical Shifts: We Are Getting Bigger (and Shorter?)

It’s weird to think about, but humans haven't always been this size. In the mid-19th century, the average American man was about 5'7". Better nutrition and less disease during childhood allowed us to grow taller. But in the last decade, some data suggests American height is plateauing or even slightly dipping compared to some European nations like the Netherlands, where the average man is over six feet tall.

Weight, however, hasn't plateaued. The "average" has shifted so far that what we see as "normal" today would have looked significantly overweight to someone in 1950. This "creeping normality" makes an average weight and height chart a bit of a moving target. If you’re comparing yourself to the average person in a country where 40% of the population is obese, "average" isn't exactly the gold standard for health.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Black Death Map of Spread Still Terrifies Historians Today

Better Ways to Measure Yourself

If the chart is broken, what do you use?

- Waist-to-Height Ratio: This is honestly way more predictive of health than BMI. Take a piece of string, measure your height, then fold it in half. If it doesn't fit around your waist, you might have too much visceral fat. Simple.

- Relative Fat Mass (RFM): Researchers at Cedars-Sinai developed this. It uses your height and waist circumference to estimate body fat percentage. It’s significantly more accurate than BMI for people with different body types.

- Blood Markers: Your A1C, your triglycerides, and your HDL/LDL ratios tell a story your scale can't. You can be "overweight" on a chart but have the metabolic profile of an Olympic swimmer.

- Performance and Mobility: Can you walk up three flights of stairs without gasping? Can you sit on the floor and get up without using your hands? These are the metrics that actually correlate with longevity.

The Mental Trap of the Number

We have to talk about the psychological toll. I’ve seen people lose 50 pounds, feel amazing, then see they are still in the "overweight" category on an average weight and height chart and spiral into a depression. It’s a trap. These charts were designed for population health—for governments to plan healthcare budgets and for insurance companies to set premiums—not for you to judge your worth in the mirror.

Focus on "body composition" rather than "weight." Two people can both weigh 180 pounds at 5'9". One has 35% body fat and is pre-diabetic; the other has 15% body fat and runs marathons. The chart sees them as identical. You are not a data point.

Actionable Steps for Using Height and Weight Data

Stop obsessing over the grid. If you want to use an average weight and height chart effectively, use it as a starting point, not the finish line.

- Track your trends: Weigh yourself under the same conditions (morning, empty stomach) and look at the weekly average. Ignore daily spikes.

- Measure your waist: Keep it under half your height. This is the single best "low-tech" health hack available.

- Get a DEXA scan: If you really want to know what's going on, a Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) scan will tell you exactly how much of your weight is bone, muscle, and fat. It’s the gold standard.

- Focus on habits, not targets: Instead of aiming for a specific number on a chart, aim for 150 minutes of zone 2 cardio and two days of resistance training per week. The "average" weight will take care of itself.

The reality is that health is nuanced. We want it to be simple—we want a chart to give us a "yes" or "no" on our health. But life isn't a spreadsheet. Use the average weight and height chart to see where you sit in the broad spectrum of the human experience, then go out and build a body that actually functions the way you need it to.

Ignore the "perfect" number. Find the number where you feel strong, your blood work is clean, and you have the energy to live your life. That's the only chart that matters.