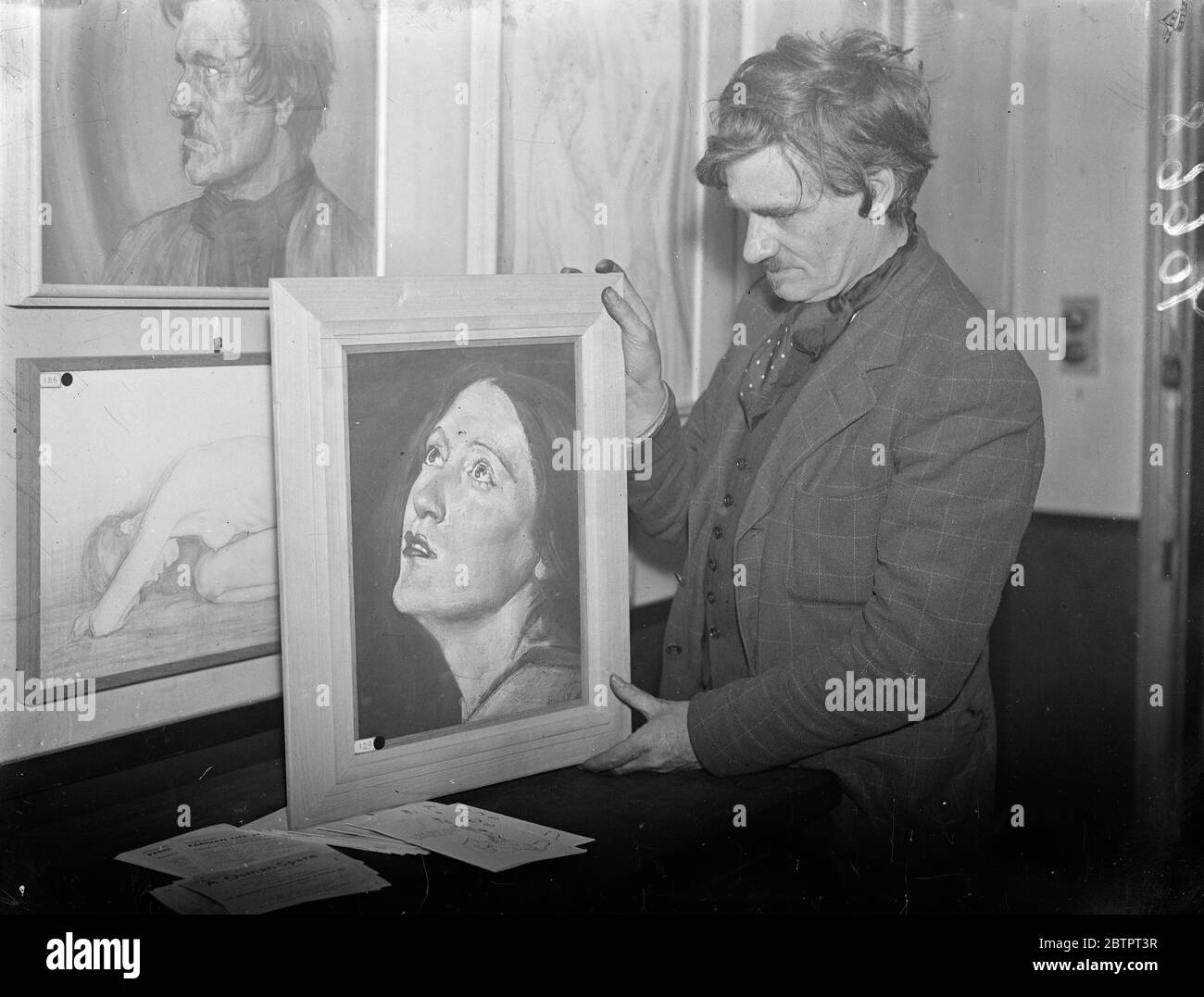

He was a prodigy. At sixteen, Austin Osman Spare became the youngest artist to ever exhibit at the Royal Academy. Critics back in 1904 were losing their minds, calling him the next Aubrey Beardsley or even a rival to George Frederic Watts. He had the world at his feet. But then, he just... stopped playing the game. Instead of high-society portraits and gallery galas, Spare chose a basement in South London, surrounded by stray cats and the "cockney" spirits he claimed to see in the shadows.

If you look at his work today, it feels hauntingly modern. It’s gritty. It’s visceral. It doesn’t look like the stiff, Victorian art of his era. Honestly, Spare was the original punk. He turned his back on the art establishment to pursue something much weirder: a blend of subconscious drawing and occult philosophy that would eventually lay the groundwork for what we now call Chaos Magic.

Most people get him wrong. They think he was just some eccentric warlock or a failed painter who went crazy. That’s a massive oversimplification. He was a technical genius who happened to believe that the human mind was a gateway to something ancient.

Why Austin Osman Spare Was Way Ahead of His Time

Spare’s technique was called automatic drawing. Long before the Surrealists like André Breton or Salvador Dalí were claiming they had invented "psychic automatism," Spare was already doing it. He would sit with a pencil, clear his mind, and let his hand move without conscious control. He wanted to bypass the "ego" entirely. He believed that the conscious mind was a filter—a boring, restrictive filter—and that the real meat of human existence lived in the "Atavistic Resurgence."

Basically, he thought we all had the memories of every ancestor, every animal, and every cell we ever evolved from buried in our DNA.

His art reflects this. You’ll see a perfectly rendered, classical face that suddenly dissolves into a swarm of distorted limbs or monstrous features. It’s unsettling because it’s so technically perfect. He wasn't drawing monsters because he couldn't draw people; he was drawing the monsters he felt were hiding inside the people.

The London Underground and the Cult of the Lower Class

While his contemporaries were painting duchesses in silk gowns, Spare was drawing the people of the Borough. He loved the working class of South London. He saw a raw, psychic energy in the "old girls" at the local pub that he didn't see in the refined elite.

🔗 Read more: Dr Dennis Gross C+ Collagen Brighten Firm Vitamin C Serum Explained (Simply)

He didn't just paint them; he lived among them. He lived in poverty for most of his life, often trading drawings for a beer or a bit of food. This wasn't because he was a failure. He had plenty of chances to be rich. He just didn't care. He once famously turned down an offer to paint Adolf Hitler, allegedly telling the messenger that if Hitler wanted to be famous, he should go paint himself. It’s a bit of a legendary anecdote, but it perfectly sums up his stubbornness.

The Invention of Sigils and the Magic of the Mind

You can't talk about Austin Osman Spare without talking about his book, The Book of Pleasure (Self-Love): The Psychology of Ecstasy. It’s a dense, difficult read. It reads like a mix of Nietzsche, Freud, and a fever dream. But inside those pages is the birth of modern sigilization.

Sigils are basically symbols created to represent a specific desire. Spare’s method was simple:

- Write down a wish.

- Cross out all the repeating letters.

- Mash the remaining letters into a single, abstract stylized drawing.

- Forget about the wish entirely.

By forgetting it, he believed the "seed" of the desire would drop into the subconscious and start working its magic without your conscious anxiety getting in the way. It’s a psychological hack disguised as sorcery. Today, you see this everywhere in pop culture and modern spirituality, but Spare was the guy who codified it in a cold London flat over a hundred years ago.

The Zos Kia Cultus: A Religion of One

Spare called his personal philosophy the Zos Kia Cultus.

- Zos represented the body, the "I," the physical vessel.

- Kia was the "Atmospheric I," the nameless, formless soul.

He wasn't interested in joining a church or an occult group like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. In fact, he briefly joined Aleister Crowley’s A∴A∴, but the two men hated each other. Crowley, the "Great Beast," found Spare too chaotic and "unrefined." Spare found Crowley too obsessed with ritual and ego.

💡 You might also like: Double Sided Ribbon Satin: Why the Pro Crafters Always Reach for the Good Stuff

Spare’s magic was lonely. It was about the individual. He believed you didn't need fancy robes or ancient Egyptian incantations. You just needed your own mind and a pencil. This "Do It Yourself" approach is exactly why he’s become a cult hero for independent artists and fringe thinkers today.

Misconceptions: Was He Actually "Mad"?

People love the "mad artist" trope. It’s easy. It sells books. But if you look at Spare’s letters and the accounts of his friends—people like Frank Letchford—he wasn't some rambling lunatic. He was sharp. He was funny. He was just deeply disinterested in the "real world" as most people define it.

During the Blitz in World War II, a bomb hit his studio. He was badly injured and lost the use of his hands for a while. Most people would have given up. Spare just retrained himself. He started painting again, his style becoming even more ethereal and pastel-driven. He didn't see the war as a political event; he saw it as a massive, tragic psychic eruption.

His later years were spent in a tiny flat in Brixton. He held "Home Exhibitions" where people could come buy a masterpiece for the price of a few pints of ale. He was happy. He was surrounded by his cats and his "shadows." When he died in 1956, he was buried in an unmarked grave, almost entirely forgotten by the art world he once conquered as a teenager.

How to Appreciate Spare Today

If you want to understand Spare, don't start with a biography. Look at the lines. Look at how he uses "sidereal" perspectives—tilting the world just enough to make it feel wrong. Look at his "anamorphic" drawings where a face only appears if you look at the paper from a certain angle.

He was a master of the "in-between."

📖 Related: Dining room layout ideas that actually work for real life

- Realism vs. Abstraction: He proved you could do both in the same stroke.

- Science vs. Magic: He viewed magic as a form of psychology we just hadn't labeled yet.

- Success vs. Integrity: He chose the latter, every single time.

Actionable Ways to Explore the Spare Legacy

To really get a handle on what Spare was doing, you need to look past the surface-level "spooky" reputation. His influence is hidden in plain sight.

- Check out the Geraldine Beskin collection: The Watkins Books owner in London is a wealth of knowledge on Spare. If you’re ever in London, that’s your home base.

- Study the "Automatic" method: Don't just read about it. Try it. Sit with a piece of paper and draw without thinking. It’s harder than it sounds and reveals a lot about your own mental "noise."

- Read "The Book of Pleasure": It’s public domain now. Skip the parts that don't make sense and focus on his drawings. The art is the real text.

- Look for the influence in modern media: From the chaos magic in comic books like The Invisibles by Grant Morrison to the dark, distorted aesthetic of modern horror films, Spare’s fingerprints are everywhere.

Austin Osman Spare didn't want to be a celebrity. He wanted to be a conduit. He succeeded. While his name isn't as famous as Picasso's, his ideas have leaked into the collective unconscious, exactly the way he intended. He remains the patron saint of the outsiders, the weirdos, and anyone who believes there’s more to the world than what we see in the light of day.

How to Identify Real Spare Art

If you’re ever lucky enough to find a piece that looks like his, look for the signature. He often used a monogram—a stylized "AOS." But more importantly, look for the eyes. Spare had a way of drawing eyes that seemed to look through the viewer rather than at them. There’s a specific "intensity" in his line work that is almost impossible to forge. His work often features "satyrs" or distorted, goat-like figures, which were his way of representing the primal, creative force of nature.

Understanding Spare isn't about learning dates and titles. It’s about accepting that the mind is a very deep, very dark well, and that some people are brave enough to climb down into it with nothing but a charcoal stick and a dream.