History is usually written by the winners, but sometimes the losers leave behind a better soundtrack. That’s basically the deal with Auferstanden aus Ruinen, the East German national anthem. If you grew up in the West, you probably think of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) as just a gray, concrete wall or a Stasi file. But for people who lived through it, the music was something else entirely. It wasn't just a song. It was a weirdly beautiful, deeply ironic, and eventually silenced piece of art that almost became the anthem for a unified Germany.

Think about that for a second.

Usually, when a country collapses, its symbols go into the trash. Statues fall. Flags get burned. But the East German national anthem refused to go quietly. Even today, if you play those opening bars in a crowded room in Leipzig or Berlin, you’ll see people of a certain age get a strange look in their eyes. It’s not necessarily nostalgia for the Soviet bread lines; it’s a connection to a melody that, for a few years, actually promised something hopeful.

The Birth of a "Socialist" Masterpiece

In 1949, the GDR was a brand new experiment. The Soviets needed a brand. They needed an anthem that didn't sound like the old Nazi "Deutschlandlied" but still felt German. It had to be grand. It had to be "antifascist."

Johannes R. Becher, a poet who would later become the Minister of Culture, wrote the lyrics. He was a guy who’d spent time in exile in Moscow, so he knew exactly how to toe the party line while still sounding poetic. Then you have Hanns Eisler. Honestly, Eisler is the real MVP here. He was a student of Arnold Schoenberg, a brilliant composer who had been kicked out of the U.S. during the McCarthy era because of his communist leanings. Eisler sat down and hammered out a melody that was catchy but dignified. It didn't sound like a military march; it sounded like a hymn for people who were tired of war.

Auferstanden aus Ruinen—"Risen from Ruins."

The first time it was performed, people were floored. It was objectively good. It captured the mood of 1949 perfectly. Germany was literally a pile of rubble. The idea of turning "towards the future" (der Zukunft zugewandt) wasn't just a socialist slogan; it was a survival necessity. Everyone was digging bricks out of the street.

When the Lyrics Became a Problem

Here is where it gets weird. For about twenty years, everyone sang the words. "Germany, united fatherland," the lyrics went. Becher and Eisler actually wanted a united Germany back then. They weren't thinking about a permanent wall. They were thinking about a socialist Germany that would eventually swallow the West or at least merge with it.

🔗 Read more: Charlie Kirk Shooting Investigation: What Really Happened at UVU

But then the 1970s happened.

The GDR leadership, specifically Erich Honecker, decided that the whole "united fatherland" thing was a liability. They wanted to be their own thing. They wanted "delimitation" (Abgrenzung) from the West. Suddenly, the official East German national anthem had "illegal" lyrics. You couldn't sing them anymore. If you sang "Deutschland, einig Vaterland" in public, you were basically asking for a chat with the secret police.

Imagine having a national anthem you aren't allowed to sing.

For nearly two decades, the East German national anthem was an instrumental-only affair. Military bands played the melody. Schools taught the music. But the words were scrubbed from textbooks. It was one of the most awkward pivots in political history. The government was so scared of the idea of unity that they silenced their own poet laureate. This created a bizarre cultural vacuum where the melody became a vessel for whatever people wanted to project onto it.

The 1990 Controversy: The Anthem That Almost Was

When the Wall came down in 1989, everything was up for grabs. People were talking about new flags, new constitutions, and definitely new music. There was a very real movement to make the East German national anthem—or at least its lyrics—part of the new, unified Germany.

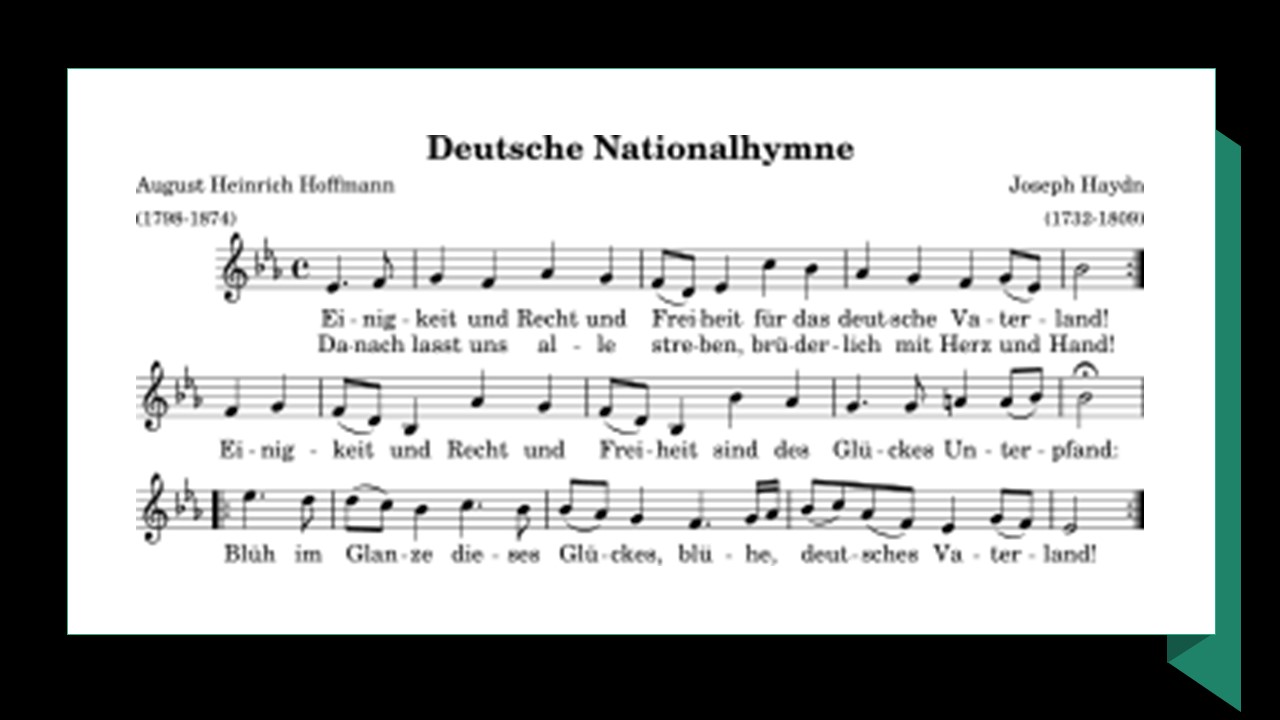

Why? Because the West German anthem (the third verse of the Deutschlandlied) carried a lot of historical baggage. Even though the third verse is about "Unity and Justice and Freedom," the melody is the same one the Nazis used for the first verse ("Deutschland über alles"). For many, especially those who suffered under the Third Reich, that tune was tainted.

Lothar de Maizière, the last Prime Minister of the GDR, actually proposed a compromise. He suggested using the lyrics of Auferstanden aus Ruinen set to the music of the West German anthem, or vice versa. Some people even suggested a mashup. Leonard Bernstein, the legendary conductor, was a fan of the Eisler melody. There’s a persistent story—though musicologists debate the exact intent—that the lyrics of the East German anthem actually fit perfectly to the meter of the West German tune. You can literally sing Becher’s words to Haydn’s melody. Go ahead, try it in your head.

💡 You might also like: Casualties Vietnam War US: The Raw Numbers and the Stories They Don't Tell You

"Auferstanden aus Ruinen... und der Zukunft zugewandt..."

It fits perfectly.

In the end, Helmut Kohl and the Western establishment won out. They kept the West German anthem. They didn't want to "merge"; they wanted to "incorporate." The East German national anthem was relegated to the history books, played one last time on October 2, 1990, just before the country it represented officially ceased to exist.

The Music Itself: Was it a Rip-off?

If you listen to the East German national anthem and think it sounds familiar, you’re not crazy. There has been a long-standing "controversy" that Eisler stole the melody from a 1930s pop song called "Goodbye Johnny."

"Goodbye Johnny" was a hit for Hans Albers, a famous German actor and singer. If you play them side-by-side, the first few notes are strikingly similar. Critics in the West loved to point this out to embarrass the GDR. They called it "plagiarism."

Eisler, being a cheeky genius, basically laughed it off. In the world of classical composition, taking a folk motif or a popular phrase and elevating it into a hymn isn't stealing; it's "thematic development." Besides, Eisler’s arrangement is far more sophisticated than a cabaret tune. He took a simple sequence and turned it into something that felt like a bridge between the 18th-century Enlightenment and 20th-century socialism.

Why We Still Talk About It

The East German national anthem survives today because it represents a "what if."

📖 Related: Carlos De Castro Pretelt: The Army Vet Challenging Arlington's Status Quo

It represents the generation of Germans who genuinely believed they were building something better than the Nazi past and something more communal than the capitalist West. Even if the state itself failed miserably—and it did, with its surveillance, its walls, and its restricted freedoms—the song remained pure.

You see this in modern pop culture. The movie Good Bye, Lenin! uses the imagery of the GDR to tap into "Ostalgie" (East-nostalgia). The anthem is a huge part of that. It’s a shortcut to a feeling of collective purpose that many people feel is missing in the modern, hyper-individualistic world.

Also, let's be real: as a piece of music, it's just better than most anthems. It’s not bombastic or aggressive. It doesn't talk about "blood watering our furrows" like the French anthem or "bombs bursting in air" like the American one. It talks about flowers, youth, and not being beaten down by the past. That’s a powerful message regardless of your politics.

How to Experience the Anthem Today

If you want to actually understand the weight of this song, don't just read about it. You need to hear it in context.

- Visit the DDR Museum in Berlin: They have interactive exhibits where you can hear the anthem played in different settings—from school assemblies to state funerals. It gives you the "vibe" of the era.

- Watch 1989 News Footage: Look for the clips of protesters in Leipzig. In the early days of the Peaceful Revolution, some people still sang the anthem because they were holding the government accountable to its own lyrics: "Germany, united fatherland."

- Compare the "Meter": If you’re a music nerd, grab a sheet of music for the Deutschlandlied and try singing the Becher lyrics. It’s a fascinating exercise in how rhythm and politics intersect.

The East German national anthem is a ghost. It haunts the reunified Germany as a reminder that the East didn't just bring the Stasi and the Wall to the marriage; they brought art, hope, and a vision for a future that, for a brief moment, sounded pretty damn good.

Actionable Insight for History Buffs:

If you're researching the GDR, stop looking only at the political decrees. Look at the cultural output. The fact that the government banned the lyrics to its own anthem is the single best metaphor for why the GDR eventually collapsed. It was a state that became terrified of its own founding ideals. To truly understand the "East German soul," you have to understand the silence that followed the music in the 1970s and 80s. Check out the Hanns Eisler archives in Berlin for a deeper look at how he navigated the pressure of writing for a regime that eventually censored his collaborators.