You probably think you know your "type." Maybe you're the one who double-texts when someone goes quiet, or perhaps you're the person who feels suffocated the moment things get serious. We talk about "red flags" and "anxious-avoidant traps" like they’re modern dating inventions, but the truth is, the blueprint for your entire love life was likely drafted in a small, observation room in Baltimore back in the 1960s. That’s where attachment theory by Ainsworth took a massive leap from abstract psychology into the messy, tangible reality of human connection.

Mary Ainsworth didn't just sit in an ivory tower. She watched. She waited. She noticed things other people missed.

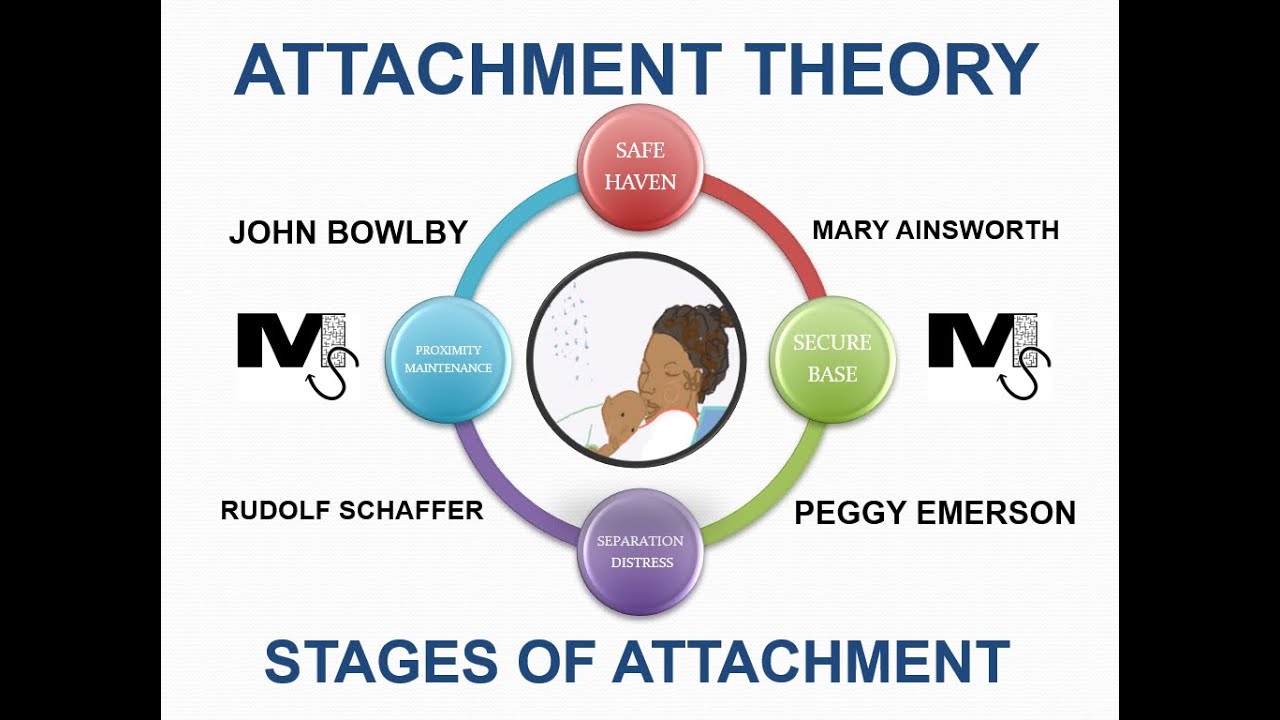

Before she came along, John Bowlby had already proposed the basic idea that infants need a "secure base." It sounds logical now. Back then? It was revolutionary. But Bowlby was the theorist; Ainsworth was the one who provided the receipts. She created the "Strange Situation" protocol, an experiment so simple yet so revealing that it basically cracked the code on how humans bond. If you’ve ever wondered why some people handle conflict with grace while others shut down completely, you're looking at the ripple effects of her research.

The Strange Situation that changed everything

Imagine a small room. There are toys on the floor. A mother and her one-year-old enter. Then, a stranger walks in. The mother leaves. The baby is left with a stranger, then left alone, and then—this is the crucial part—the mother returns.

Ainsworth wasn't actually that interested in the crying. Most babies cry when their mom leaves. That’s just survival. What she cared about was the reunion.

How does the child react when the caregiver walks back through that door? That single moment of reconnection told Ainsworth everything she needed to know about the internal working model of that child's mind. She realized that the "attachment theory by Ainsworth" wasn't just about whether a parent was "good" or "bad." It was about attunement. It was about whether the child felt seen.

She identified three original patterns. Later, researchers added a fourth, but Ainsworth’s trio remains the bedrock of developmental psychology.

The Secure Base

About 60% to 70% of the kids in her original studies fell into this group. When mom came back, they might have been upset, but they sought her out, got a hug, calmed down quickly, and went back to playing. They trusted the world. Honestly, it’s the gold standard we’re all supposed to be aiming for. These kids grew up believing that if they were in trouble, someone would help. Simple, right? But it requires a parent who is consistently responsive, not just occasionally nice.

🔗 Read more: Ingestion of hydrogen peroxide: Why a common household hack is actually dangerous

The Anxious-Ambivalent Response

This one is heartbreaking to watch on the old tapes. These babies are inconsolable when the caregiver leaves. When the mother returns, they do this weird "push-pull" dance. They want to be picked up, but then they kick or arch their backs away. They’re angry. They don't trust the reunion. Why? Because in their short lives, the care they received was likely inconsistent. Sometimes mom was there; sometimes she was distracted or intrusive. The child learned they had to "up the ante" to get their needs met.

The Avoidant Strategy

Then there were the "cool" babies. When mom left, they didn't seem to care. When she came back, they ignored her. For a long time, people thought these kids were just "independent." Ainsworth knew better. When researchers checked the heart rates of these avoidant infants, their pulses were racing. They were under massive stress; they just learned to mask it because they knew—implicitly—that expressing a need wouldn't result in comfort. It's a survival mechanism: shut down to avoid the pain of rejection.

Why her time in Uganda mattered

A lot of people think attachment theory is just a Western, middle-class phenomenon. They’re wrong.

Before the Baltimore studies, Ainsworth spent years in Uganda. She lived among the Ganda people, observing 26 families with an intensity that would make modern researchers sweat. She saw the same patterns there. She realized that while the way mothers interacted with babies might look different across cultures, the fundamental need for a secure base was universal. It’s biological. It's in our DNA.

She noticed that the most "secure" infants in Uganda weren't necessarily the ones held the most, but the ones whose mothers could read their signals accurately. If the baby was hungry, they got fed. If the baby wanted to explore, they were let go. It was a dance of autonomy and connection.

The messy transition to adulthood

You aren't a baby in a playroom anymore, but the ghost of that playroom follows you into your bedroom and your boardroom.

In the late 80s, researchers Cindy Hazan and Phillip Shaver realized that the patterns in attachment theory by Ainsworth mapped almost perfectly onto adult romantic relationships.

💡 You might also like: Why the EMS 20/20 Podcast is the Best Training You’re Not Getting in School

- Secure adults find it relatively easy to get close to others and don't worry about being abandoned. They can communicate needs without feeling like they’re "too much."

- Anxious adults (the "ambivalent" kids) are often obsessed with their relationships. They need constant reassurance. They’re hyper-sensitive to changes in a partner’s mood.

- Avoidant adults value "independence" above all else. They view intimacy as a trap. When things get real, they pull away, often claiming their partner is "too needy."

It’s easy to judge the avoidant or the anxious. But if you look through Ainsworth’s lens, you see these aren't character flaws. They are adaptations. An avoidant person isn't "cold"—they are protecting themselves from a world they learned was unresponsive. An anxious person isn't "crazy"—they are using the only tool they ever had to ensure they aren't forgotten.

The nuance we often miss

We love labels. We love taking a quiz and saying, "I'm avoidant, that's just how I am."

But Ainsworth’s work was never meant to be a life sentence. She believed in the "internal working model," which sounds permanent, but it’s actually a plastic, living thing. Scientists call this Earned Security. You can start out as an avoidant or anxious child and, through therapy or a long-term relationship with a secure partner, actually rewire your brain.

There is also a fourth category often discussed alongside Ainsworth: Disorganized Attachment. This was identified later by her student Mary Main. This happens when the caregiver is a source of fear rather than a source of safety. It’s the most complex and difficult pattern to navigate because the child's biological instinct (run to the parent) conflicts with their survival instinct (run away from danger). It’s important to mention because it reminds us that attachment exists on a spectrum of trauma and safety.

Real-world implications you can't ignore

If you think this is just for psychologists, look at the prison system. Look at the foster care system. Look at how we treat "difficult" employees.

When we understand attachment theory by Ainsworth, we stop asking "What's wrong with you?" and start asking "What happened to you?"

In a workplace, an avoidant employee might be your best researcher but a terrible collaborator because they don't trust the group. An anxious employee might be the most dedicated worker but burn out because they can't handle a vague email from the boss. Recognizing these patterns allows for better management, better parenting, and—frankly—a lot more self-compassion.

📖 Related: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable steps for your own attachment

You can't go back and change how you were treated in 1995. But you can change how you respond to those old echoes today.

1. Identify your "Protest Behavior"

When you feel disconnected from someone you love, what do you do? Do you pick a fight? Do you go silent for three days? Do you call them twenty times? This is your attachment system in overdrive. Recognizing the behavior as it happens is the first step toward stopping it.

2. Seek out "Secure" influences

Stability is contagious. If you're anxious, dating someone avoidant is like throwing gasoline on a fire. You need people who are consistent, who say what they mean, and who don't play games. This goes for friendships, too.

3. Practice "Effective Communication"

Instead of saying "You're always working," (anxious protest), try "I'm feeling a bit disconnected and I'd love for us to have dinner without phones tonight." It feels vulnerable. It feels "weak" to an avoidant person. But it’s the only way to build a secure base in adulthood.

4. Be the "Sensitive Caregiver" to yourself

Ainsworth’s work showed that the key to security was sensitivity to signals. Start paying attention to your own internal signals. Are you tired? Are you lonely? Are you actually angry at your partner, or are you just scared they're leaving? Don't ignore your own "cries."

5. Observe, don't just react

Next time you feel that "spark" with someone, ask yourself: Is this chemistry, or is this my attachment system recognizing a familiar (and perhaps unhealthy) pattern? Sometimes what we call "boring" is actually just "secure."

The legacy of Mary Ainsworth isn't just a set of categories. It’s a roadmap for empathy. She showed us that our need for each other isn't a weakness; it's a biological imperative. Whether you're navigating a new relationship or trying to understand your own history, her work offers a way to see the invisible threads that pull us together—or push us apart.

Recognizing your style is the beginning of changing it. Focus on small, consistent acts of transparency. Trust isn't built in grand gestures; it’s built in the "reunion" moments, just like those babies in the Baltimore playroom. When things go wrong, and they will, the magic is in how you come back together.