Ever tried to measure the exact edge of a cloud? You can't. It’s a fuzzy, misty mess that thins out until it’s just... gone. Atoms are basically the same thing. When we talk about atomic radius, we aren't talking about a hard marble you can measure with a tiny ruler. We are talking about probability zones where electrons like to hang out.

Most people think of atoms like little solar systems. They picture a solid nucleus with planets orbiting in neat, predictable tracks. That’s the Bohr model, and while it’s great for passing a 9th-grade quiz, it’s not exactly how reality works. In the real world, electrons are chaotic. They exist in "clouds." Because these clouds don't have a sharp "crust," defining the size of an atom is actually a bit of a nightmare for scientists.

Defining the Indefinable

So, how do we actually measure atomic radius? Since we can't find the "edge," we look at the distance between two nuclei. Imagine two tennis balls pushed together; you measure the distance from the center of one to the center of the other and cut that number in half.

Depending on how the atoms are bonded, the radius changes. You've got your covalent radius for atoms sharing electrons. Then there's the metallic radius for, well, metals. And then there’s the van der Waals radius, which is basically the "personal space" an atom demands when it’s not bonded to anything at all. It’s a bit like measuring a person's "size" by how close they let people stand next to them in an elevator versus how much space they take up when they're hugging someone.

The Periodic Table’s Weird Tug-of-War

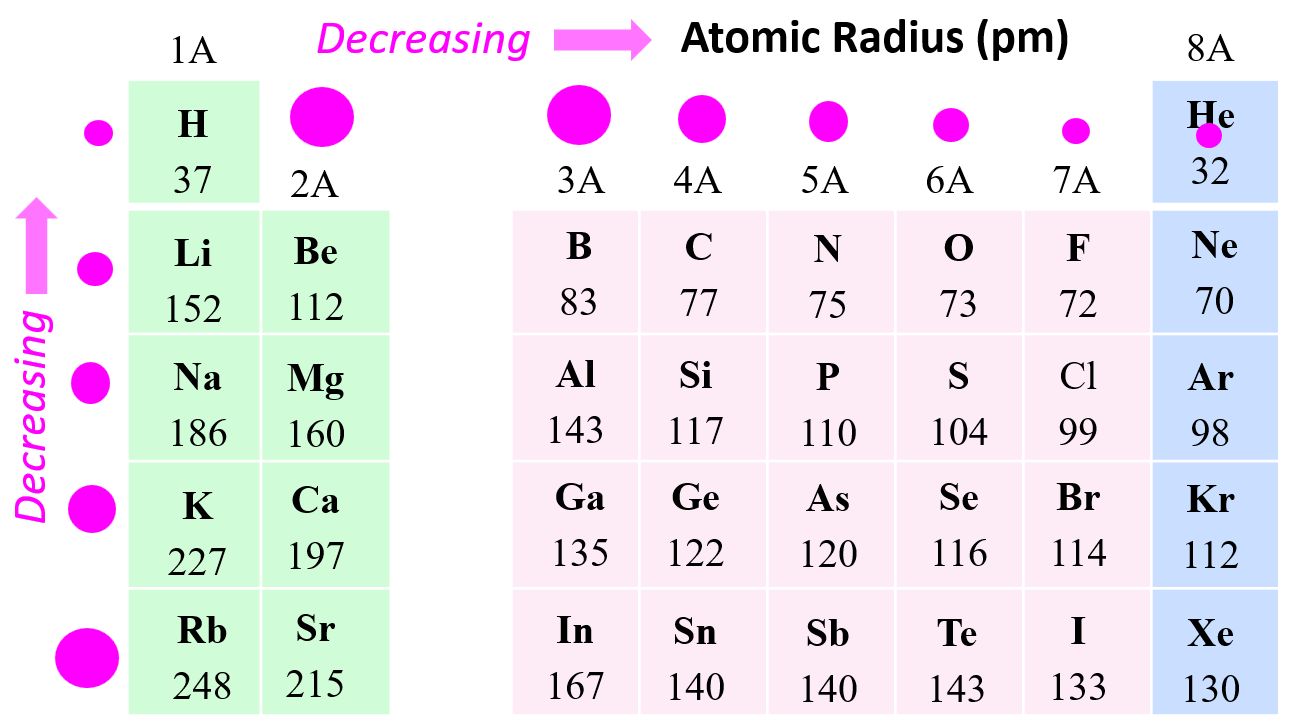

If you look at the periodic table, you’d assume that adding more stuff—more protons, more neutrons, more electrons—would always make an atom bigger.

You’d be wrong.

Chemistry is counterintuitive. As you move from left to right across a row (a "period"), atoms actually get smaller. It feels backwards, right? You’re adding protons! You’re adding electrons! But here is the trick: as you add protons to the nucleus, the positive charge gets stronger. This is called the Effective Nuclear Charge. Think of the nucleus like a giant magnet. The more protons you add, the stronger that magnet pulls on the electron clouds, yanking them inward. Even though the atom is "heavier," it’s being squeezed tight by its own internal gravity.

Then, things flip when you go down a column.

When you move down a group, atoms get significantly larger. Why? New layers. Each row down adds a brand-new electron shell. It’s like putting on a bulky winter parka over a t-shirt. Even if the nucleus is trying to pull those electrons in, the inner layers of electrons act like a shield. This "shielding effect" blocks the pull of the nucleus, letting the outer electrons drift further away.

💡 You might also like: Finding a Food App Development Company That Doesn't Waste Your Money

Why Does This Actually Matter?

Size determines personality in the world of elements. An atom's atomic radius dictates how it reacts with the world.

Take Cesium. It’s a massive atom. Its outermost electron is so far away from the nucleus that the nucleus barely has a grip on it. It’s like a parent trying to keep an eye on a toddler three blocks away. Because that electron is so loosely held, Cesium is incredibly reactive. Drop it in water and it doesn't just fizz—it explodes.

On the other hand, you have Fluorine. Tiny. Greedy. Because its electrons are so close to the nucleus, the pull is intense. Fluorine doesn't want to give up electrons; it wants to steal yours. This size difference is the literal foundation of why some things are toxic, why some things conduct electricity, and why your phone battery works the way it does.

Trends That Break the Rules

Of course, science is never that clean. There are "anomalies."

Take the Lanthanide Contraction. If you look at the elements in the sixth period, they are weirdly small. You’d expect them to be huge compared to the row above them, but they aren't. This happens because the "f-orbitals" are terrible at shielding. They’re like a screen door trying to stop a magnet's pull—they just don't do the job. So, the nucleus reaches right through them and pulls those outer electrons in way tighter than anyone expects.

Then there's the whole "ionic radius" thing. When an atom loses an electron to become a cation (positive ion), it shrinks instantly. It’s like losing twenty pounds overnight. But when an atom gains an electron to become an anion (negative ion), it swells up. The extra electron adds more "repulsion"—the electrons start pushing away from each other because they need more room.

Putting it Into Practice

If you’re trying to understand material science or even just pass a chemistry exam, don't just memorize the trends. Think about the Effective Nuclear Charge versus Electron Shielding.

🔗 Read more: Is Dictionary.com For Kids Actually Better Than a Physical Book?

- Visualize the Magnet: When you move right on the table, the magnet (nucleus) gets stronger, pulling the "fuzz" (electrons) inward.

- Visualize the Layers: When you move down, you're adding physical shells. More shells = bigger atom. No exceptions.

- Compare Ions: Positive ions are always smaller than their parent atoms; negative ions are always larger.

Understanding atomic radius is basically the "cheat code" for the rest of chemistry. Once you know how big an atom is and how tightly it holds its electrons, you can predict its melting point, its reactivity, and how it will bond with other elements without ever looking at a textbook.

To truly master this, grab a blank periodic table and try to draw the "trends" as arrows. Draw a big arrow pointing down and to the left. That’s the direction of increasing size. If you can explain why that arrow points that way—mentioning the pull of the nucleus and the shielding of the shells—you understand the building blocks of the universe better than most. Use a visualization tool or an interactive periodic table like the one at Ptable.com to see these radii in 3D; seeing the actual physical scale compared to the "numbers" on the page makes the concept stick far better than rote memorization ever could.