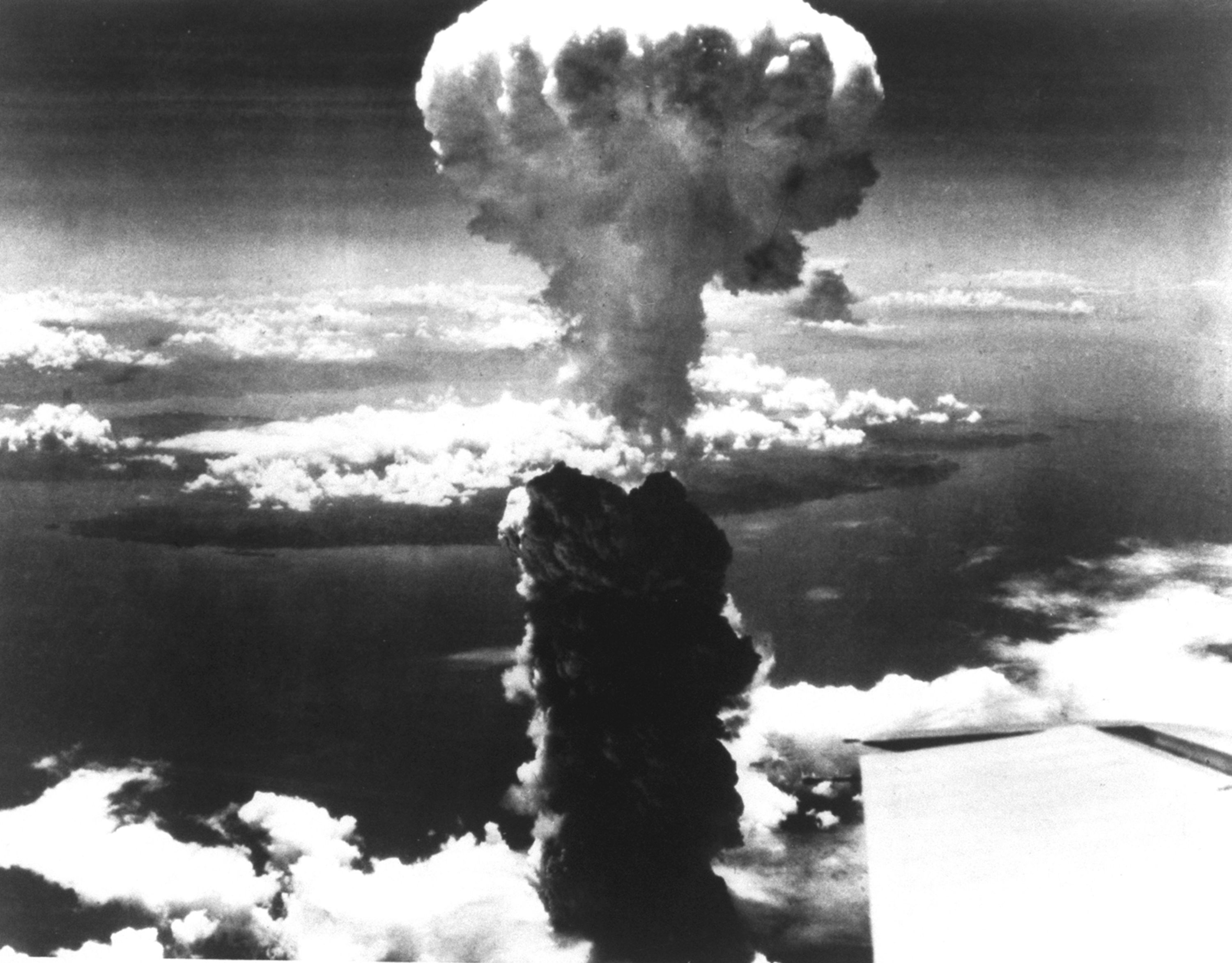

August 1945 changed everything. It wasn't just the end of a war; it was the start of a terrifyingly new kind of existence. Most of us grew up seeing that grainy, black-and-white mushroom cloud in textbooks, but the actual atomic bomb of Hiroshima and Nagasaki facts are often buried under layers of political spin and oversimplification. People think it was just two bombs, two cities, and a quick surrender. It was way messier than that.

The reality is heavy.

Take "Little Boy," the uranium bomb dropped on Hiroshima. It didn't even "hit" the ground. It was designed to explode about 1,900 feet in the air to maximize the "mach stem" effect, which basically means the shockwave bounces off the ground and meets the incoming blast to create a double-force wall of pressure. It’s a level of calculated destruction that's honestly hard to wrap your head around. When the blast hit, the center of the fireball was hotter than the surface of the sun for a split second. People literally vanished.

The Target That Wasn’t Supposed to Be

Most people don't realize that Nagasaki wasn't even the primary target for the second mission. It was Kokura. On August 9, 1945, the B-29 bomber Bockscar spent nearly an hour circling Kokura, but the city was covered in thick clouds and smoke from a nearby firebombing in Yahata. The crew had strict orders to drop the bomb visually, not by radar. Since they couldn't see the target and were running low on fuel, they pivoted to their secondary option. That’s how Nagasaki entered the history books—by a literal twist of weather.

It's a haunting thought. Thousands of lives were spared in one city and lost in another because of a few clouds.

📖 Related: Fire in Idyllwild California: What Most People Get Wrong

The Physics of the "Gadgets"

The two bombs were fundamentally different technologies. "Little Boy" was a gun-type weapon. It fired a "bullet" of uranium-235 into a larger mass of uranium to trigger the explosion. It was so simple that scientists didn't even test the design before dropping it; they were that sure it would work. On the other hand, "Fat Man"—the Nagasaki bomb—was a plutonium implosion device. It was incredibly complex, using high explosives to squeeze a plutonium core until it reached criticality.

The energy release? Beyond comprehension.

Hiroshima's blast was roughly 15 kilotons.

Nagasaki’s was about 21 kilotons.

But even with those massive numbers, the efficiency was terrifyingly low. In the Hiroshima bomb, less than a gram of matter—about the weight of a paperclip—was actually converted into pure energy. That tiny speck of mass caused the destruction of an entire city.

The Human Cost and the "Hibakusha"

We talk about numbers—140,000 dead in Hiroshima, 70,000 in Nagasaki by the end of 1945—but the survivors, known as Hibakusha, lived through a unique kind of hell. Many didn't die from the initial blast or the heat. They died weeks later from "purple spots" on their skin, their hair falling out in clumps, and their white blood cell counts plummeting. This was acute radiation syndrome. At the time, Japanese doctors had almost no idea what they were looking at. They were treating burns, but the patients were dying from the inside out because their bone marrow had been destroyed.

👉 See also: Who Is More Likely to Win the Election 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

The Shadow People

You’ve probably heard of the "shadows" etched into stone. It’s one of those atomic bomb of Hiroshima and Nagasaki facts that sounds like an urban legend, but it’s scientifically grounded. The intense thermal radiation—the flash—instantly bleached the concrete and stone surfaces of the city. If a person was standing in front of a wall or sitting on steps, their body shielded that specific spot from the radiation. The "shadow" isn't actually the person's remains; it's the original color of the stone, while everything around it was lightened by the heat.

Tsutomu Yamaguchi: The Man Who Lived Twice

If you want to talk about the sheer statistical impossibility of survival, you have to talk about Tsutomu Yamaguchi. He was in Hiroshima for a business trip on August 6. He was badly burned but survived. He then caught a train—yes, the trains were still running in some capacity—back to his hometown.

His hometown? Nagasaki.

He was in his boss's office on August 9, describing the horror of the first bomb, when the second one went off. He lived through both. He lived to be 93. It’s one of the few stories from that week that feels like a miracle, though he spent much of his life campaigning against nuclear weapons because he knew better than anyone what they could do.

✨ Don't miss: Air Pollution Index Delhi: What Most People Get Wrong

The Myth of the Warning

There is a common belief that the U.S. dropped millions of leaflets warning citizens that an atomic bomb was coming. This is... kinda true but mostly misleading. The "LeMay leaflets" did warn Japanese civilians to evacuate certain cities because of firebombing, but they did not mention a nuclear weapon, and they didn't specifically name Hiroshima as a target for the atomic strike. The element of surprise was a tactical choice. The U.S. military wanted the psychological shock of a "new and most cruel bomb" to force a surrender.

Why This Still Matters for Your Security Today

Understanding these facts isn't just about a history lesson. It’s about the shift in global power dynamics that we’re still feeling in 2026. The world moved from "conventional" war to a "deterrence" model.

If you're looking to actually process this information beyond just reading a screen, here are the most impactful ways to engage with this history:

- Read the "Hiroshima" Article by John Hersey: Originally published in The New Yorker in 1946, it follows six survivors. It remains the gold standard for understanding the human perspective of the blast.

- Visit the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) Website: They have the most extensive data on the long-term health effects of the survivors. It's the primary source for almost all modern radiation safety standards.

- Watch "Black Rain" (Kuroi Ame): This 1989 film captures the social stigma survivors faced in Japan. People were afraid that radiation sickness was contagious or that it would cause genetic defects in future generations, leading to decades of discrimination in marriage and employment.

- Examine the "Enola Gay" Exhibit Digitally: The Smithsonian’s records on the restoration of the B-29 provide a technical look at the mission that is often separated from the emotional reality of the ground.

The jump from TNT to Nuclear was a "one-way door" in human history. We can't un-know how to do this. By looking at the specific, grit-filled details of what happened in those three days in August, we get a clearer picture of why the global community is so obsessed with non-proliferation today. It isn't just about "big bombs." It's about a weapon that targets the very cellular structure of life and leaves shadows where people used to stand.