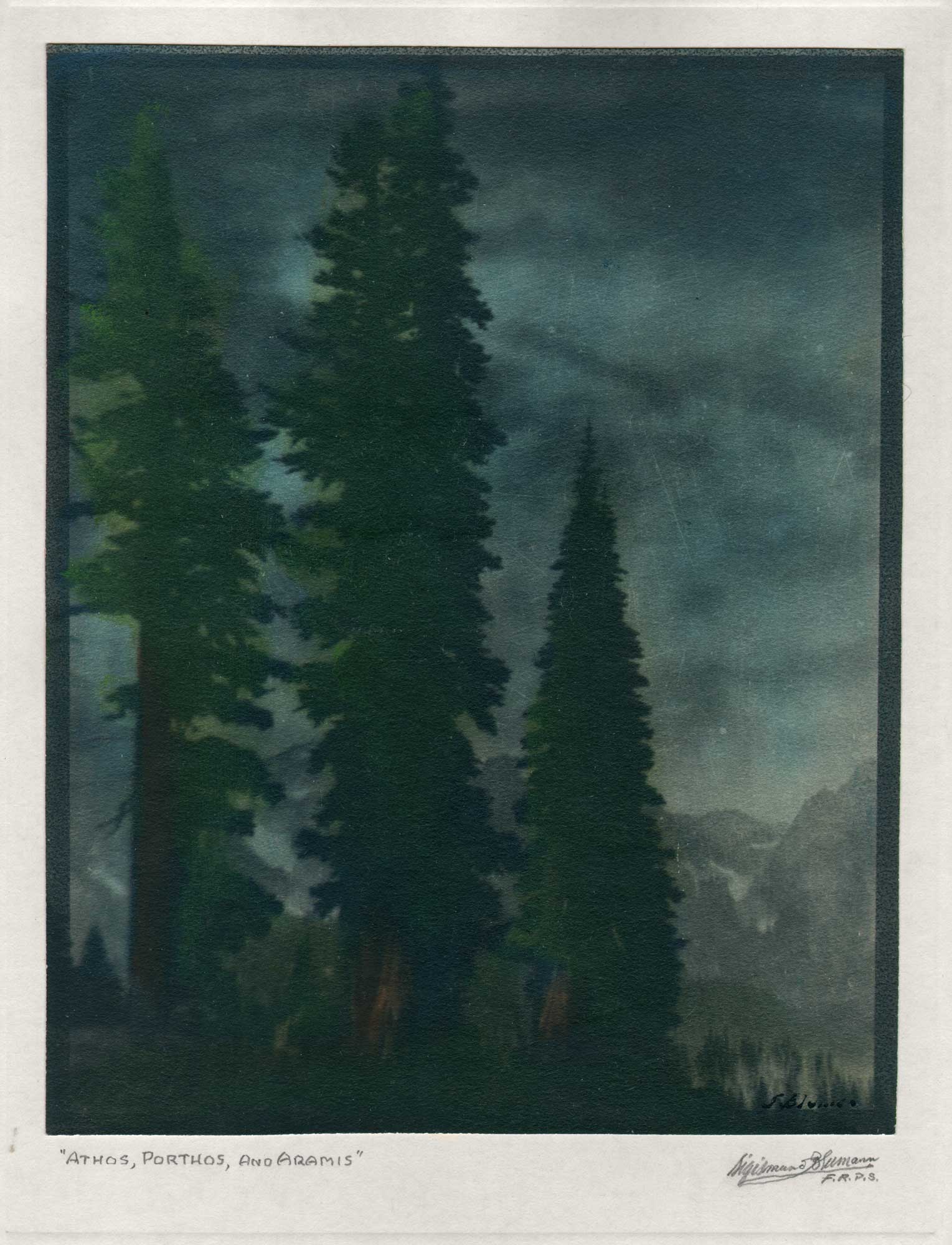

You probably think you know Athos, Porthos, and Aramis. They’re the guys in the floppy hats, right? The ones swinging from chandeliers and shouting about "all for one" while fighting off waves of Cardinal Richelieu’s guards.

Thanks to Disney, Richard Lester, and about a dozen other film adaptations, the Three Musketeers have become caricatures. We see them as the jock, the drunk, and the priest. But Alexandre Dumas wasn't just spinning yarns when he wrote Les Trois Mousquetaires in 1844. He was actually digging into real history.

Those three dudes? They existed. Sorta.

The real Athos, Porthos, and Aramis weren't just archetypes for d'Artagnan to bounce off of. They were actual men of the sword living in a 17th-century France that was much grittier, bloodier, and more politically unstable than any PG-rated movie suggests. If you want to understand why these characters have survived for nearly two centuries, you have to look past the velvet tabards.

The Ghost of Athos: More Than a Sad Drunk

In the novels, Athos is the "older brother" figure. He’s the Comte de la Fère, a man hiding a devastating past involving a branded criminal wife (the infamous Milady de Winter) and a bottle of wine that’s never quite empty enough. Dumas painted him as the ultimate aristocrat—cold, refined, and deeply depressed.

The real guy? Armand de Sillègue d’Athos d’Autevielle.

He didn't live long enough to be a mentor. Records show he was born around 1615 in the Béarn region. He joined the Musketeers because his cousin was Monsieur de Tréville, the captain of the company. Nepotism was basically the LinkedIn of the 1640s. Sadly, the real Athos died in 1643, likely from wounds sustained in a duel or a street skirmish near the Pré-aux-Clercs, a notorious dueling ground in Paris.

He never saw d’Artagnan become a legend. He was just another young cadet who lost his life in the chaotic violence of the French capital.

When we look at the literary Athos, we see the personification of the dying feudal nobility. He represents a class of men who were being sidelined by the rise of absolute monarchy under Louis XIV. His melancholy isn't just about a girl; it's about the loss of a world where a man’s word and his sword were the only laws that mattered.

💡 You might also like: Anne Hathaway in The Dark Knight Rises: What Most People Get Wrong

Porthos and the Legend of the Giant

Porthos is usually the comic relief. He’s the big guy. He likes food. He likes clothes. He likes bragging. In the movies, he's often portrayed as a lovable oaf, but in the books, he’s actually quite tragic. He’s a man who tries to buy his way into respectability.

Isaac de Porthau was the real-life inspiration.

He wasn't necessarily a giant who could snap muskets with his bare hands, but he was a soldier of the Guards before joining the Musketeers. Like Athos, he was from the Béarn region. The Porthau family wasn't even noble to start with; his father was a secretary to the King. This is a crucial detail that Dumas leaned into. Porthos is the "new money" of the 17th century. He’s desperate to look the part, which is why he wears that famous baldric that’s gold on the front and plain buff on the back.

He’s a poser. But a loyal one.

Honestly, Porthos is the most "human" of the trio. He wants what most of us want: a nice house, good food, and for people to think he’s important. While Athos is stuck in the past and Aramis is looking toward the heavens (or the next bedroom), Porthos is just trying to live his best life. He eventually retires to his estates, but in the sequels, his strength becomes his downfall. There's a scene in The Vicomte of Bragelonne where he literally holds up a cave roof with his shoulders until his legs give out.

It’s one of the most heartbreaking deaths in literature.

Aramis: The Most Dangerous Musketeer

If you think Aramis is just the "pretty boy," you’ve been misled. In the books, he’s terrifying.

Aramis (inspired by Henri d’Aramitz) is a man of contradictions. He wants to be a priest, but he can’t stop getting into duels and sleeping with noblewomen. He’s the intellectual. He speaks Latin. He plots. By the end of the saga, he’s not even a soldier anymore; he’s a Bishop and the General of the Jesuits.

📖 Related: America's Got Talent Transformation: Why the Show Looks So Different in 2026

He’s essentially the 17th-century version of a black-ops agent.

The real Henri d’Aramitz was a lay abbot, which sounds religious but was actually a secular position that came with some church land and income. He was a family man, eventually marrying and having four kids. He didn't spend his old age plotting to replace King Louis XIV with a twin brother in an iron mask.

But Dumas saw something in the idea of a soldier-priest. He created a character who represents the shift from "might makes right" to "knowledge is power." Aramis is the only one of the original four who survives until the very end. He wins because he’s the only one willing to play the political game. He’s sleek, secretive, and honestly, a bit of a snake.

You’ve got to respect the hustle.

Why the "Three Musketeers" Are Actually Four

It’s the great irony of the title. D'Artagnan is the protagonist, but the title ignores him.

The reason this dynamic works is the chemistry of the "quad." Charles de Batz de Castelmore d'Artagnan (the real one) was a superstar. He actually served Louis XIV for decades, became the "Captain-Lieutenant" of the Musketeers, and died at the Siege of Maastricht in 1673.

The interplay between these four men is a masterclass in character writing. You have:

- Athos: The stoic past.

- Porthos: The physical present.

- Aramis: The calculating future.

- D’Artagnan: The bridge between them all.

When they clash with the Cardinal's guards, it's not just a fight. It's a clash of ideologies. Richelieu wanted to centralize power and end the era of independent-minded swordsmen. The Musketeers were the last gasp of a certain kind of masculine independence.

👉 See also: All I Watch for Christmas: What You’re Missing About the TBS Holiday Tradition

The Realities of 17th-Century Combat

We need to talk about the dueling. It wasn't the clean, choreographed dance you see on screen. It was messy. It was illegal.

Louis XIII and Richelieu hated dueling. They saw it as a waste of good soldiers. Men were killing each other over minor insults—a bumped shoulder, a "wrong" look, or a disagreement over a horse. The Musketeers were notorious for flouting these laws.

They didn't just use rapiers. They used main-gauches (left-hand daggers), cloaks to parry, and even their pommels to smash faces. It was brutal. When Porthos hits someone, they don't just fall down; they break. When Athos fights, it’s with a cold, surgical precision that's meant to end the threat immediately.

How to Tell the Difference in Adaptations

If you're watching a movie and want to know if it's "book-accurate," look at how they treat the trio's flaws.

If Athos is just a grumpy guy without a drinking problem and a dark secret about his ex-wife, they’ve sanitized him. If Porthos is just "the fat one" and doesn't show a deep-seated insecurity about his social standing, they’ve missed the point. And if Aramis isn't constantly trying to leave the army to join the church (only to get pulled back by a woman or a fight), he’s not the real Aramis.

The 1973 Richard Lester version is widely considered the gold standard for capturing the grit. The 2014 BBC series The Musketeers did a decent job of modernizing the characters while keeping their core trauma intact. But honestly? Read the book. It’s a soap opera with swords.

Actionable Takeaways for History and Fiction Buffs

If this dive into the lives of Athos, Porthos, and Aramis has sparked an interest, don't just stop at the movies.

- Read "The Three Musketeers" Unabridged: Most English versions are trimmed. Find a translation that keeps the political intrigue. It’s much longer than you think.

- Visit the Musée de l'Armée in Paris: If you’re ever in France, go to Les Invalides. They have an incredible collection of 17th-century weapons and armor that show you exactly what these men carried.

- Explore the Sequels: Most people don't know there are two more books—Twenty Years After and The Vicomte of Bragelonne. They follow the characters into middle age and old age. They are arguably better and more complex than the first book.

- Look Up the "Gascon" Culture: All these men (and the real ones) were from Gascony or the surrounding regions. Understanding the "Gascon" stereotype—boastful, brave, hot-headed, and fiercely loyal—explains why they acted the way they did.

The legend of Athos, Porthos, and Aramis endures because they represent different facets of the human experience. We all have moments where we feel the weight of the past like Athos, the desire for status like Porthos, or the ambition of Aramis. They aren't just characters; they're us, with better hats and sharper swords.