March 1971 was a weird time for rock. The Beatles were done. Hendrix and Joplin were gone. Everyone was looking for the next thing, but nobody expected it to come from a group of long-haired guys from Macon, Georgia, who looked more like roadies than rock stars. When The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East was recorded over three nights in Manhattan, the band was basically broke. They were road warriors living in a van, playing for gas money and beer. They had two studio albums out, but they hadn't really captured that lightning-in-a-bottle energy that happened when Duane Allman and Dickey Betts started trading guitar solos.

That live album changed everything. It didn't just make them famous; it redefined what a live recording could be. Before this, live albums were usually cheap cash-ins with terrible sound quality. This was different. Producer Tom Dowd treated the mobile recording unit like a laboratory. He captured the grease, the sweat, and the sheer telepathic connection between six musicians who were playing for their lives. Honestly, if you listen to the opening slide riff of "Statesboro Blues," you can almost smell the stale cigarettes and floor wax of the old theater.

The Magic of the March 1971 Residency

Bill Graham's Fillmore East was the "Church of Rock and Roll." It wasn't just a venue; it was a proving ground. The Allmans were the house band in many ways. They played there so often they had their own favorite deli around the corner. For the March 12-13 shows, the band was actually the middle act on a bill that featured Johnny Winter and Elvin Bishop. Talk about a powerhouse lineup.

Duane Allman was the undisputed leader. He was 24 years old, possessed by some kind of cosmic blues spirit, and pushed everyone else to play harder. You can hear it in "Whipping Post." It's not just a song; it's a 23-minute marathon. Most bands would fall apart trying to keep a 11/4 time signature steady for that long, but Butch Trucks and Jaimoe—the two drummers—locked in like a machine. It's that "double drummer" attack that gave the band its heavy, rolling thunder sound.

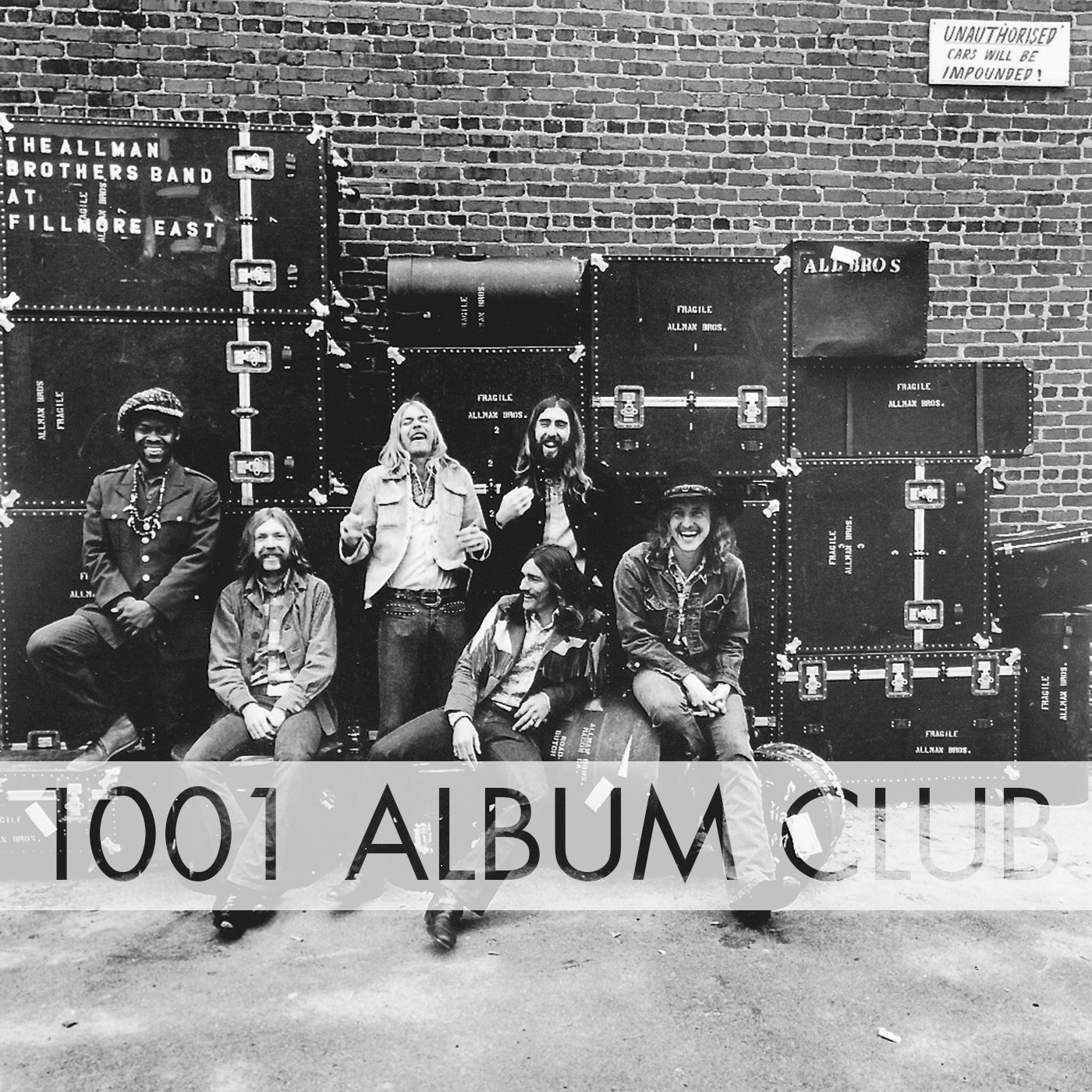

Most people don't realize that the iconic cover photo wasn't even taken at the Fillmore. It was shot in a cold alleyway in Macon. The band looked miserable because it was freezing, until a drug dealer walked by and the band cracked up laughing. That’s the shot. The one where they look like the coolest gang in the world. It’s authentic. Nothing about The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East was manufactured by a PR firm.

Breaking Down the "In Memory of Elizabeth Reed" Jam

If you want to understand why this album is the gold standard, you have to look at "In Memory of Elizabeth Reed." Dickey Betts wrote it after seeing a headstone in a cemetery where the band used to hang out (and occasionally do other things). It’s jazz disguised as rock.

The interplay is insane. Duane and Dickey don't just play over each other; they weave. One starts a phrase, the other finishes it. It's conversational. It's like watching two master painters work on the same canvas without bumping elbows. Tom Dowd, who had worked with Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles, knew he was hearing something historic. He famously told the band to just keep playing and he'd handle the tapes.

📖 Related: The Masked Singer Season 10 Explained: Why Ne-Yo as Cow Changed the Game Forever

There’s a specific moment in the solo where the organ swells—Gregg Allman’s Hammond B3—and it feels like the whole room is lifting off the ground. That’s not studio magic. That’s what it sounded like in the room. The fans who were there still talk about it like a religious experience.

Why the Sound Quality Beats Modern Records

We have better tech now, sure. We have Pro Tools and infinite tracks. But we don't have the room. The Fillmore East had incredible acoustics, and the way the microphones captured the "bleed" between instruments created a massive, natural wall of sound.

- The Les Paul Factor: Duane played a '59 Cherry Sunburst, and Dickey used a '57 Goldtop. These are the holy grails of guitars.

- The Amps: They were pushing Marshall stacks to the absolute limit. You can hear the tubes sizzling.

- The Mix: Tom Dowd edited the jams. He cut pieces together from different nights, but he did it so seamlessly that you'd never know. The version of "You Don't Love Me" is actually a composite of two different takes, edited together because the first half of one was better than the second half of the other.

It’s raw. Nowadays, live albums are polished until they’re boring. They fix the missed notes and the flat vocals. On The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East, the imperfections are what make it perfect. You hear the floorboards creaking. You hear the audience screaming when the lights go down. It's alive.

The Tragedy That Followed

Success was brief. Only a few months after the album was released and started climbing the charts, Duane Allman died in a motorcycle accident. He was only 24. A year later, bassist Berry Oakley died in a similar accident just blocks away.

This album is the definitive document of the original lineup. It’s the only time we got to hear them at their absolute peak before the wheels came off. It’s a bittersweet listen. You’re hearing the birth of Southern Rock, but you’re also hearing a goodbye.

Berry Oakley’s bass playing on this record is often overlooked. He wasn't just playing roots; he was playing lead bass. Listen to the intro of "Whipping Post." That growling, distorted bass line is the heart of the whole track. Without Berry, the band never quite had that same "heavy" swing again.

Debunking the "Jam Band" Label

A lot of people lump the Allmans in with the Grateful Dead or Phish. While they definitely jammed, they were different. The Allmans were rooted in the blues and jazz. They weren't just noodling around. Every solo had a beginning, a middle, and a climax. Duane Allman studied John Coltrane and Miles Davis. He wanted the band to sound like Kind of Blue but with louder guitars.

The structure of the songs on The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East is actually very tight. Even the long tracks have "milestones" they hit. They knew exactly where they were going, even if it took twenty minutes to get there. It wasn't aimless. It was intentional.

What You Can Learn From This Recording Today

If you’re a musician or just a fan of "real" music, there are a few takeaways from this record that still apply in 2026.

👉 See also: Why the Toy Story 3 Chatter Telephone is the Movie’s Most Underestimated Character

First, chemistry is everything. You can't fake the connection these six guys had. They lived together in a big house (The Big House in Macon), they ate together, and they rehearsed constantly. That’s why they could improvise without looking at each other.

Second, less is more—except when more is more. They knew when to back off and let the vocals shine, but they also knew when to open the throttle. Gregg Allman's voice was incredible for a guy in his early 20s. He sounded like he’d lived three lifetimes.

Third, don't be afraid of the "long game." In an era of 15-second TikTok clips, sitting down and listening to a 20-minute blues jam seems crazy. But there’s a payoff in the long-form stuff that you just can't get from a short pop song. It’s about the journey, not just the hook.

How to Experience the Fillmore East Legacy Now

The physical building in New York is gone—it's an apartment building now—but the music is everywhere. If you really want to get into it, look for the "Deluxe Edition" or the "Six-Disc Box Set." It includes every note played over those two nights.

You’ll hear the mistakes. You’ll hear Duane telling the crowd to settle down. You’ll hear them restart songs. It’s the closest thing we have to a time machine.

👉 See also: Seven Seas of Rhye: What Freddie Mercury Actually Meant

To truly appreciate the nuances of the performance, follow these steps:

- Get a decent pair of headphones. Don’t listen to this on your phone speaker. You need to hear the separation between the two drummers—one panned left, one panned right.

- Listen to "Statesboro Blues" first. It’s the perfect intro. It sets the tone and shows off Duane’s slide work immediately.

- Read up on the gear. If you’re a guitar nerd, looking up the "Fillmore East Pedalboard" (spoiler: there basically wasn't one) adds a layer of respect for how they got those tones just from their hands and amps.

- Watch the footage. There isn't much high-quality video of this specific run, but there are clips from 1970 that show the band’s intensity. It helps put a face to the sound.

This album isn't just a piece of history; it’s a living thing. Every time someone picks up a guitar and tries to play a slide solo, they’re chasing the ghost of Duane Allman at the Fillmore East. It’s the high-water mark for American rock and roll. Period.