Math often feels like a series of arbitrary rules designed by people who enjoyed making life difficult for the rest of us. Honestly, most people hear the words associative property, commutative property, and distributive property and immediately flash back to a dusty 7th-grade classroom where they were staring at a chalkboard, wondering when lunch started. But these aren't just "school rules." They’re basically the physics of how numbers move. If you understand them, you stop memorizing steps and start seeing how math actually functions under the hood.

Math is just logic. It’s consistent.

The Commutative Property: Order Just Doesn't Matter (Sometimes)

Think about your morning routine. You put on your left sock, then your right sock. Does it matter? Not really. You still have two socks on. That is the essence of the commutative property. It’s the idea that you can swap the position of numbers without changing the result.

In the world of addition, $a + b = b + a$. If you have five dollars and someone gives you three, you have eight. If you have three dollars and someone gives you five, you still have eight. It’s simple. It's intuitive. We do this every day when we’re counting change or figuring out if we have enough seats at a dinner table.

Multiplication works the exact same way. $5 \times 3$ is 15. $3 \times 5$ is 15. You can visualize this as a grid. A $3 \times 5$ grid of tiles has the same number of squares as a $5 \times 3$ grid; you just rotated the rectangle.

But here’s where people get tripped up: it doesn't work for everything. Subtraction is the enemy here. $10 - 2$ is 8, but $2 - 10$ is $-8$. Order is everything when you're taking things away. Division is just as picky. If you try to commute $10 / 2$, you get 5. If you swap them to $2 / 10$, you’re looking at $0.2$. So, the commutative property is a specialized tool for addition and multiplication. Use it elsewhere, and the logic falls apart immediately.

Why the Associative Property is About Your Social Circle

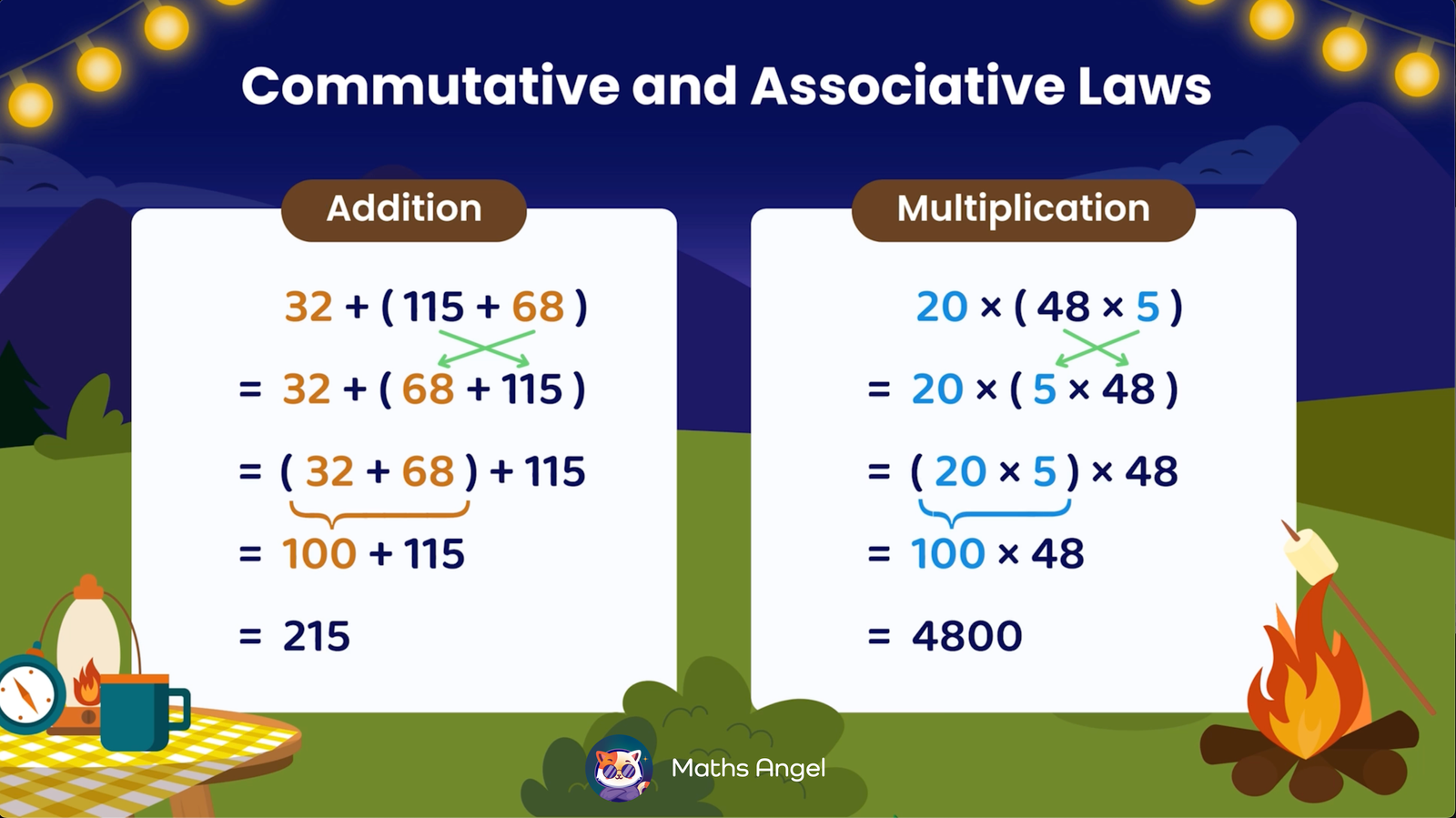

The associative property sounds like "association," which is actually a great way to remember it. It’s about who is hanging out with whom. While the commutative property is about moving numbers around, the associative property is about how we group them using parentheses.

✨ Don't miss: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

Imagine you're adding three numbers: $2 + 3 + 4$.

You could add the 2 and 3 first to get 5, then add the 4 to get 9.

Or, you could add the 3 and 4 first to get 7, then add the 2 to get 9.

Mathematically, it looks like this: $(a + b) + c = a + (b + c)$.

It’s a subtle difference, but it’s huge for mental math. If you're at a grocery store trying to add $$12.50$, $$7.00$, and $$3.50$ in your head, your brain probably uses the associative property without you realizing it. You’ll instinctively group the $$12.50$ and $$3.50$ first because they make a nice, round $$16$. Then you add the $$7$. It’s way easier than going in a strict linear order.

Just like its cousin, this property only plays nice with addition and multiplication. Subtraction ruins the party. $(10 - 5) - 2$ gives you 3. But $10 - (5 - 2)$ gives you 7. The parentheses change the entire meaning of the equation because they change which number is being subtracted from what. This is why software developers and engineers spend so much time obsessing over syntax; one misplaced "association" and the bridge collapses—or at least the code crashes.

The Distributive Property: The Great Multiplier

If the first two properties are about flexibility, the distributive property is about efficiency. It is the bridge between addition and multiplication. It basically says that if you are multiplying a sum by a number, you can "distribute" that multiplier to each individual piece of the sum.

The formula is $a(b + c) = ab + ac$.

🔗 Read more: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

Let's say you're buying lunch for four friends. Each person wants a burger for $$8$ and a soda for $$2$. You could add the burger and soda together first ($$10$) and then multiply by 4 people to get $$40$. That’s $(8 + 2) \times 4$.

Or, you could calculate the total cost of the burgers ($4 \times 8 = 32$) and the total cost of the sodas ($4 \times 2 = 8$) and add them up. $32 + 8 = 40$. You distributed the "4" to both the burger price and the soda price.

This is the property that usually scares people when they see it in algebra with variables like $x$ and $y$. But it’s the exact same logic. When you see $3(x + 4)$, you’re just saying you have three of everything inside that box. Three $x$’s and three 4’s.

The Mental Math Hack You Never Realized You Had

Most people who claim they are "bad at math" actually use the distributive property every time they calculate a tip or a discount.

Say you want to find 15% of $$40$.

Your brain might break 15% into 10% and 5%.

10% of 40 is 4.

5% is half of that, which is 2.

$4 + 2 = 6$.

You just used the distributive property: $40 \times (0.10 + 0.05) = (40 \times 0.10) + (40 \times 0.05)$.

💡 You might also like: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

It’s a cognitive shortcut. By breaking complex numbers into smaller, manageable chunks, we bypass the need for a calculator. This is exactly how "math whizzes" do large multiplications in their head. To multiply $12 \times 15$, they don't do the long multiplication table in their mind. They do $(12 \times 10) + (12 \times 5)$. That’s $120 + 60$, which is 180. Easy.

Common Mistakes and Why They Happen

The biggest hurdle is "over-generalization." We like patterns. Our brains want the rules to apply everywhere. We learn that $2 + 3 = 3 + 2$ and we assume $2^3 = 3^2$.

It doesn't. $2^3$ is 8. $3^2$ is 9.

Exponents, division, and subtraction are "non-commutative." They are rigid. They have a specific direction. Most errors in high school algebra come from a student trying to apply the associative property to a subtraction problem or forgetting to distribute a negative sign across a whole set of parentheses.

If you have $-3(x - 4)$, you aren't just distributing the 3. You’re distributing the "negative." That turns the $-4$ into a $+12$. This is the "gotcha" moment that kills grades, but if you visualize it as distributing a "debt" or an "opposite," it starts to make more sense.

Real World Usage: It’s Not Just for Homework

In computer science, these properties are used to optimize code. Compilers—the programs that turn human code into machine code—actually look for ways to use the associative and commutative properties to rearrange calculations so they run faster. If a computer can group operations to use less memory or fewer clock cycles, it will.

In logistics and business, the distributive property is used to calculate bulk shipping rates and tax across different regions. If you have a shipping cost applied to a hundred different items, you can either calculate it item-by-item or sum the items and apply the cost once. The math guarantees the result is the same, so businesses choose the method that is easier to track.

Practical Next Steps to Master These Concepts:

- Audit your mental math: The next time you're at a store, try to calculate a 20% discount by breaking it into two 10% chunks. See the distributive property in action.

- Identify the "non-commuters": When you're dealing with any process—whether it's cooking, coding, or fixing a car—ask yourself: "Is this commutative?" Can I swap the order? In baking, adding dry to wet or wet to dry sometimes matters. In math, it's about knowing when the order is a suggestion and when it's a law.

- Visual Grouping: If you're teaching a child or struggling yourself, use physical objects like coins or LEGO bricks. Move them around to see that a group of $(3 + 2) + 1$ is the same as $3 + (2 + 1)$. Physicalizing the associative property makes it much harder to forget.

- Watch the Negatives: If you're doing algebra, treat the negative sign like a "flip" switch that must be applied to every single term inside a parenthesis when distributing.

Understanding these properties isn't about passing a test. It’s about recognizing the underlying symmetry of the universe. When you stop seeing numbers as static things and start seeing them as parts of a fluid system, math stops being a chore and starts being a tool.