Most people walk up to an assisted pull up machine and treat it like a chore. They climb on, set the pin to a heavy weight, and start bouncing like they’re on a pogo stick. It’s painful to watch. Honestly, if you’re using the counterbalance just to ego-lift through a range of motion you haven’t earned yet, you’re basically wasting your gym membership.

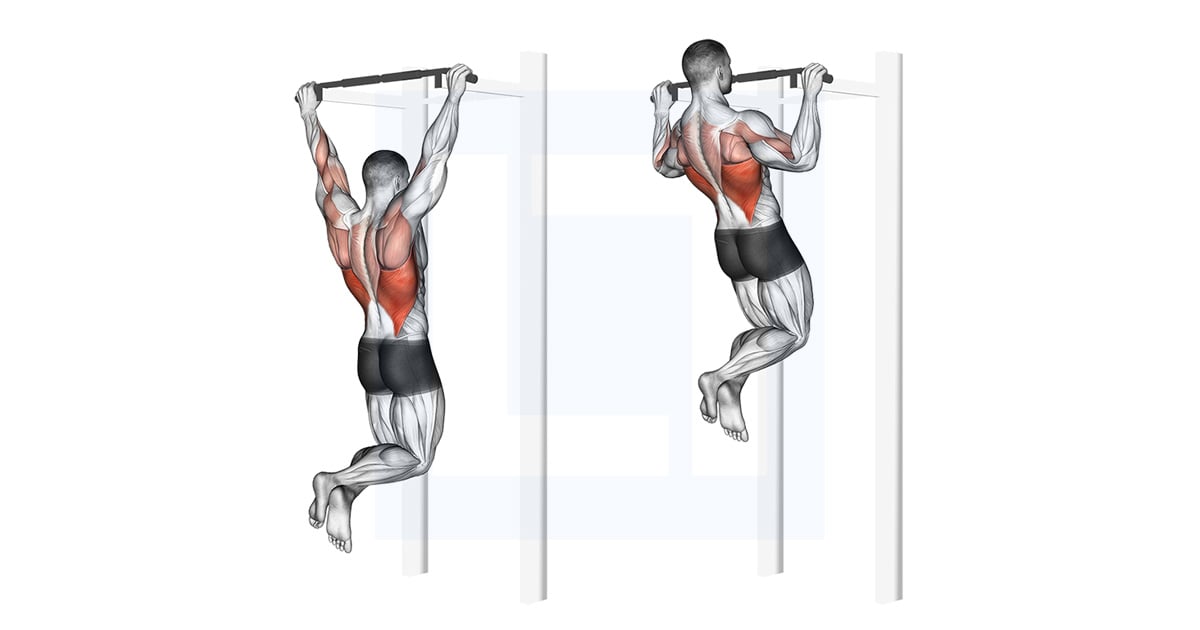

The pull-up is the king of upper body movements. It builds that wide V-taper, strengthens the lats, and makes you feel like an absolute beast. But the jump from "zero pull-ups" to "one pull-up" is a massive chasm. That’s where this machine comes in. It’s a tool. It isn't a cheat code, and it definitely isn't just for beginners who "can't do the real thing." Even high-level athletes use these to rack up volume without frying their central nervous system.

Let's get one thing straight: the weight stack on an assisted pull up machine works backward. If you set it to 100 pounds, the machine is lifting 100 pounds for you. You are only lifting the remainder of your body weight. If you weigh 180 pounds, you’re only pulling 80. It sounds simple, but you’d be surprised how many people get confused and wonder why the exercise gets "harder" when they move the pin to a lower number.

The Biomechanics of the Counterbalance

Standard pull-ups are hard because you’re fighting gravity with your entire mass from a dead stop. Most of us have a "sticking point" right at the bottom or halfway up. The beauty of the assisted pull up machine—whether it's the standing platform style or the kneeling pad version—is that it provides a consistent upward force throughout the entire arc of the movement.

However, there is a catch.

In a traditional pull-up, your legs are free. Your core has to engage like crazy to stop your body from swinging. You’re using your transverse abdominis and even your quads to stabilize. When you’re on a machine, your knees or feet are anchored to a platform. This removes almost all the stability requirements. You might feel stronger, but you’re actually becoming less "functional" in the strictly athletic sense.

Researchers like Stuart McGill, a giant in the world of spine biomechanics, often emphasize the importance of core stiffness during heavy pulls. On a machine, that stiffness is optional. You can get away with a soft midsection. If you want this to translate to a real, unassisted pull-up, you have to consciously brace your core as if that pad wasn't even there.

Kneeling vs. Standing Platforms

You’ve probably seen two main types of these machines. The kneeling version is more common in big box gyms like Planet Fitness or LA Fitness. It’s generally more comfortable but can lead to a "broken" kinetic chain because your lower legs are essentially out of the equation.

The standing version is rarer but actually better for transition. It keeps your hips in a more natural, extended position. If you have the choice, go with the standing platform. It mimics the body tension of a real pull-up much more accurately.

Why You Aren’t Getting Stronger

Here is a hard truth: if you’ve been using the assisted pull up machine for six months and you still can’t do a single bodyweight rep, you’re doing it wrong.

The most common mistake is the "Death Grip." People squeeze the bar so hard their forearms give out before their lats even wake up. Try using a thumbless grip—wrap your thumb over the top of the bar. It helps "hook" the weight and forces the force production to come from your elbows. Think about pulling your elbows into your back pockets. Don't think about pulling your chin over the bar.

Another progress-killer is the "Partial Rep." Because the machine makes it easy, people tend to cut the range of motion short at the bottom. They don't fully extend their arms because that "dead hang" position is the hardest part to initiate. If you don't train the bottom 10% of the movement, you will never be able to start a real pull-up from the floor.

The Problem with Momentum

Stop bouncing. Seriously.

When you drop down quickly, the weight stack on the machine jumps. Then, it slams back down, giving you a literal "boost" at the start of the next rep. You aren't getting stronger; you're just getting better at using physics to lie to yourself.

Slow down. Take three seconds to lower yourself (the eccentric phase) and pause for a half-second at the bottom. Then, pull. This "tempo training" is what actually builds the muscle fibers required for a strict pull-up.

Using the Assisted Pull Up Machine for Hypertrophy

If your goal isn't necessarily to do "real" pull-ups, but just to get a huge back, this machine is actually superior to the traditional version in some ways. Why? Because you can control the failure point.

In a standard pull-up, once you’re gassed, you’re done. With the assisted pull up machine, you can perform "drop sets."

- Do as many reps as possible at a low assistance (say, 20 lbs).

- When you can’t do another clean rep, quickly move the pin to 50 lbs.

- Keep going.

- Move it to 80 lbs.

This allows you to take the lats past their normal point of failure, which is the primary driver for hypertrophy (muscle growth). Bodybuilders like Dorian Yates were famous for focusing on intense, controlled movements over just "doing reps." You can apply that same logic here.

Common Myths and Misconceptions

People love to hate on this machine. You’ll hear "purists" say it’s useless. They’ll tell you to just do negatives (jumping up and lowering yourself slowly) or use resistance bands.

Are they right? Sort of.

Resistance bands are great, but they have a variable resistance curve. They provide the most help at the bottom and almost no help at the top. This is the opposite of what most people need. The assisted pull up machine provides constant assistance. It’s more predictable.

Also, don't believe the myth that this machine is bad for your shoulders. It’s actually safer for people with impingement issues because the counterbalance reduces the sheer force on the rotator cuff during the initial pull. If your shoulders hurt during pull-ups, the machine is your best friend while you work on your mobility.

A Real Training Protocol

Stop guessing. If you want to see results, follow a structured progression. Treat the machine like a bench press. Track your numbers.

- Week 1: Find a weight where you can do 3 sets of 8 reps with perfect form. No swinging. No bouncing.

- Week 2: Stay at that same weight, but try to do 3 sets of 10.

- Week 3: Drop the assistance by 10 pounds (making it harder) and aim for 3 sets of 5-6 reps.

- Week 4: Deload. Go back to higher assistance and just focus on the mind-muscle connection.

If you weigh 200 pounds and you’re using 100 pounds of assistance, your "net lift" is 100. Your goal is to get that net lift as close to 200 as possible.

Grip Variations Matter

Don't just use the wide handles. Most machines have multiple grip options:

- Wide Grip: Hits the teres major and the outer lats. Hardest version.

- Neutral Grip (palms facing each other): Easiest on the shoulders and heavy on the brachialis (forearm/bicep area).

- Underhand Grip (Chin-up style): Heavily involves the biceps.

Switching your grip every few weeks prevents overuse injuries and ensures you don't have "blind spots" in your back development.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Workout

To actually get the most out of the assisted pull up machine, you need to change your mental approach. It isn't a "lite" version of a real exercise. It's a precision instrument.

📖 Related: Protein in a Pound of Chicken Breast: What Most People Get Wrong

First, check your posture. Most people hunch their shoulders forward. Before you pull, depress your scapula—push your shoulder blades down and back. Imagine you're trying to pinch a pencil between your shoulder blades. Hold that tension throughout the entire set.

Second, adjust the weight so you can actually feel your lats working. If you feel it all in your biceps, the assistance might be too high, or your grip might be too narrow.

Finally, integrate "isometrics." On your last rep of every set, hold yourself at the very top for 5 to 10 seconds. Squeeze everything. This builds "time under tension" in the weakest part of the lift.

Move the pin one notch lower than you think you can handle. Fight for the reps. That’s where the growth happens. Stop using the machine as a crutch and start using it as a ladder.

- Test your 1RM (One Rep Max) assistance: Find the absolute minimum weight the machine needs to give you to complete one perfect rep.

- Record your body weight: Since the machine is a subtraction game, you need to know the "starting" number to track real strength gains.

- Prioritize the "Negative": Spend 4 seconds on the way down for every single rep.

- Switch to a "Neutral Grip" if you feel any clicking or snapping in your shoulders; it’s a more natural path for the humerus.

- Decrease assistance by only 5 lbs per week: Small, incremental wins lead to the eventual "first" unassisted pull-up.

Forget about how much weight is on the stack. Focus on how much of "you" is doing the work. That is the only way to eventually step off the platform and pull your own weight.