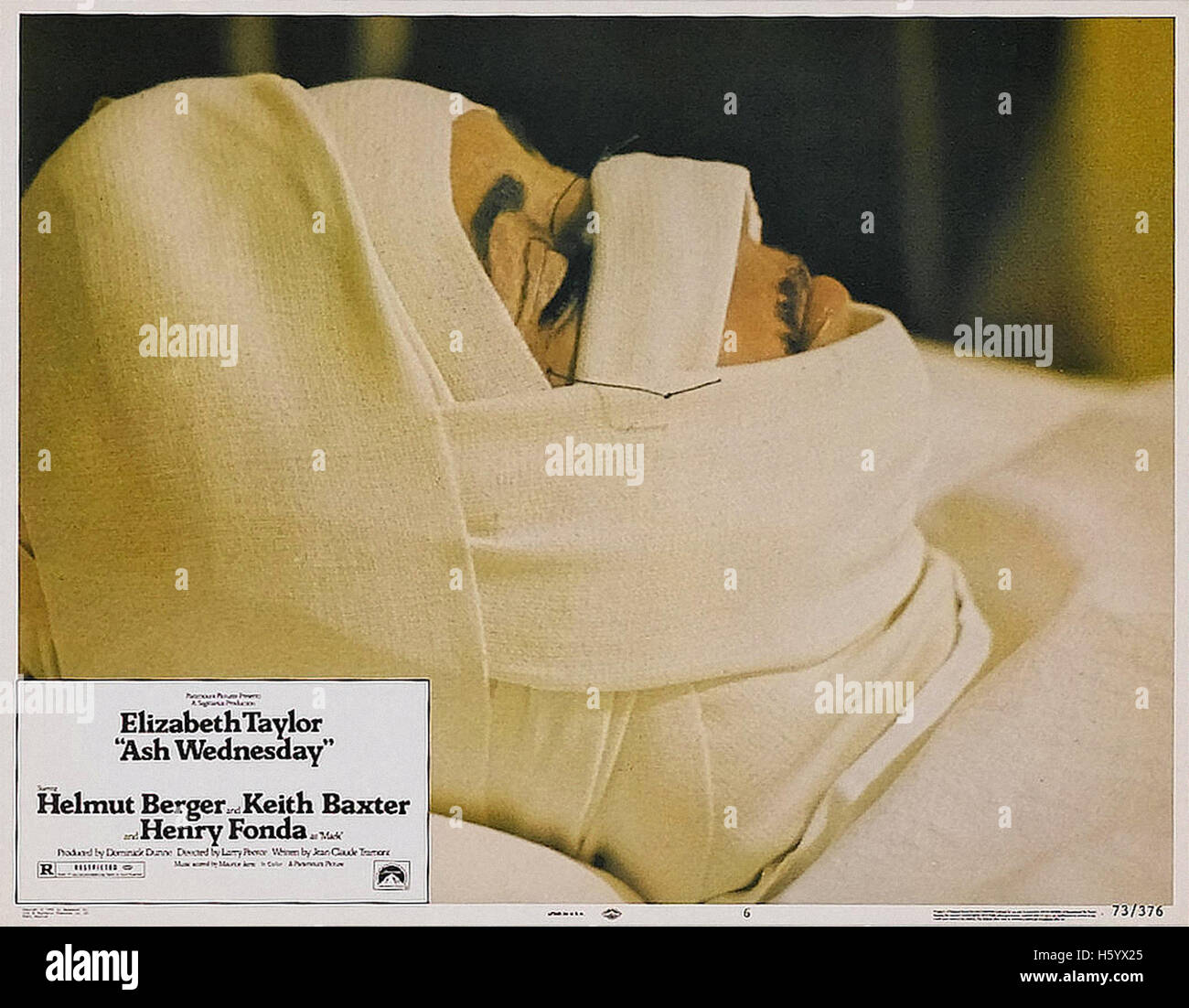

It is hard to watch. Truly. There is a scene in the Ash Wednesday movie 1973 where the camera lingers, almost cruelly, on the surgical marking of Elizabeth Taylor’s face. You see the purple ink. You see the cold, clinical reality of a woman preparing to be sliced open so she can stay beautiful.

Critics back then hated it. They called it a "glorified soap opera" and "shallow." But looking at it today, in an era where everyone has a "filter" and Botox is a lunch-break activity, Ash Wednesday feels less like a vanity project and more like a horror movie about the cost of being a woman in the public eye.

The plot is basic. Barbara Sawyer (Taylor) feels her marriage to Mark (Henry Fonda) slipping away. She’s aging. He’s distracted. So, she flies to an elite clinic in the Italian Alps to undergo a total body and face transformation. It’s a gamble. She wants to surprise him with a "new" version of herself at a ski resort, hoping the scalpel can cut away years of neglect.

The Graphic Reality of 1970s "Beauty"

Most people remember this film for one thing: the gore.

Director Larry Peerce didn't hold back. He used actual footage of a facelift operation. You see the skin being peeled. You see the stitches. It was shocking in 1973. It’s still a bit nauseating now.

Why do this? Peerce wasn't just trying to gross people out. He wanted to show the violence of the beauty standard. It wasn't enough for Barbara to just "look better." She had to bleed for it.

Elizabeth Taylor was 41 when she made this. Think about that. 41.

Today, 41 is considered the prime of a woman’s life in Hollywood (sometimes). In 1973, Taylor was being treated like a relic. The irony is that she was still arguably the most beautiful woman in the world, yet the script required her to play a "discarded" wife.

Why the Ash Wednesday Movie 1973 Failed at the Box Office

The movie didn't make money. Not much, anyway.

Part of the problem was the tone. It’s gloomy. It’s gray. Even the beautiful Italian scenery feels cold and isolating. It’s a movie about loneliness, but it was marketed as a glamorous Elizabeth Taylor vehicle. Audiences showed up expecting Cleopatra or Cat on a Hot Tin Roof energy.

✨ Don't miss: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

They got a woman sitting in a hotel room with bandages around her head, crying.

Henry Fonda is also barely in it. He shows up at the end for the big "reveal," and his reaction is... complicated. He doesn't look at her with renewed lust. He looks at her with a mix of pity and exhaustion.

It’s brutal.

Critics like Vincent Canby of The New York Times weren't kind. Canby basically said the movie was a bore, focusing more on Taylor's jewelry and furs than the actual human heart. But he might have missed the point. The jewelry is the point. Barbara is a woman who has been reduced to her surface. If the surface isn't perfect, she ceases to exist in the eyes of her husband.

The Fashion and the "Cortina" Vibe

If you can get past the surgical scenes, the film is a time capsule of high-end 70s fashion. Edith Head—the legend herself—did the costumes.

We’re talking:

- Massive fur coats that would cause a riot today.

- Oversized sunglasses that hide half the face.

- Jewelry that probably cost more than the film’s catering budget.

- Monochromatic ski outfits.

The setting is Cortina d'Ampezzo. It looks expensive. It smells like old money and cigarettes.

Taylor spends a lot of time wandering through these spaces, looking like a ghost in a designer gown. She meets a younger man, played by Helmut Berger. He’s the "distraction." He represents the validation she craves. But even their fling feels hollow. There’s a desperation to the Ash Wednesday movie 1973 that makes it hard to categorize. Is it a romance? A tragedy? A medical drama?

Honestly, it’s a character study of a woman who has no identity outside of being "The Great Beauty."

🔗 Read more: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

Facts vs. Rumors: Did Elizabeth Taylor Actually Get Surgery?

This is what everyone whispered about in 1973.

The marketing leaned into the "life imitates art" angle. People wanted to know if Taylor was using the movie to debut her own real-life facelift.

The truth is a bit more nuanced. Taylor was open about her struggles with weight and aging, but she didn't have the massive, reconstructive surgery depicted in the film at that specific time. The "surgical" shots in the movie were a mix of a hand-double, a real patient, and very clever makeup.

However, Taylor's performance is incredibly brave. She allowed herself to be filmed in unflattering light, with "age" makeup that emphasized wrinkles she didn't even have yet.

It was a meta-commentary on her own career. She was the star who was always judged by her face. By making a movie about "fixing" that face, she was poking the bear.

The Religious Symbolism You Might Have Missed

The title isn't just a date on the calendar.

Ash Wednesday marks the beginning of Lent. It’s about penance. "Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return."

Barbara is trying to defy that "dust." She is trying to stop the decay. But the movie’s title suggests that her efforts are ultimately a form of penance. She is punishing her body to save her soul (or what she thinks is her soul, which is her marriage).

There is a heavy, Catholic sense of guilt hanging over everything. The surgery isn't a "glow-up." It’s a sacrifice.

💡 You might also like: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

Is It Worth Watching Today?

Yes. But not for the reasons people watched it in 1973.

Watch it as a precursor to films like The Substance (2024). Watch it to see Elizabeth Taylor give a performance that is much better than the script allows. She brings a deep, soulful sadness to Barbara.

You’ll notice how quiet the movie is. There are long stretches where nothing happens. Barbara just waits.

Waiting for the swelling to go down.

Waiting for the phone to ring.

Waiting to feel like she is "enough."

It’s a slow burn. If you’re used to modern pacing, it might feel sluggish. But if you settle into that 70s rhythm, it’s haunting.

How to Approach the Movie Now

If you are going to seek out the Ash Wednesday movie 1973, don't go in expecting a rom-com. Go in expecting a mid-life crisis caught on 35mm film.

- Focus on the eyes. Taylor’s violet eyes are the only part of her that doesn't change after the "surgery." They remain full of a specific kind of yearning that no scalpel can fix.

- Watch the ending closely. Pay attention to Henry Fonda’s face. It’s one of the most honest depictions of a dying marriage ever put on screen.

- Compare it to "The Stepford Wives." Both films deal with the 1970s anxiety about women's bodies and the pressure to be a "perfect" object for men.

The film serves as a stark reminder that the "good old days" of Hollywood weren't all that kind to women over 35. It exposes the machinery of beauty—the literal stitches and blood—that goes into maintaining an image.

The final takeaway isn't that surgery is bad or that vanity is a sin. It’s that you can’t use a physical solution for an emotional problem. Barbara Sawyer changed her face, but she couldn't change the fact that her husband had already checked out.

Next Steps for Film History Buffs

- Research Edith Head’s Work: Look up the sketches for the Ash Wednesday costumes to see how she used clothing to "armor" Taylor’s character.

- Track Down the Soundtrack: Maurice Jarre (who did Lawrence of Arabia) wrote the score. It’s lush, sweeping, and intentionally contrasts with the coldness of the plot.

- Read the Original Reviews: Find the 1973 Variety or Village Voice clippings. Seeing how viciously the press treated Taylor’s "aging" provides vital context for why the movie feels so defensive.