Hell is a vibe. Or at least, it’s been a vibe for about two thousand years. If you walk into any major museum today, you’re almost guaranteed to find a corner where the lighting gets a bit dimmer and the canvas gets a lot bloodier. Humans are obsessed with the downstairs. We’ve spent centuries trying to figure out exactly what the "worst place imaginable" looks like, and honestly, the results are way more creative than any depiction of heaven ever was. Think about it. Pearly gates and clouds? Boring. Eternal lakes of fire, demons with faces on their stomachs, and giant frozen traitors? That’s where the real art happens.

Artistic depictions of hell aren't just about scaring people into being good, though that was definitely the "marketing" goal for a long time. They’re a mirror. They show us what we’re actually afraid of—isolation, physical pain, or just being forgotten.

The Man Who Defined the Inferno

You can't talk about this stuff without bringing up Dante Alighieri. His Divine Comedy basically handed a blueprint to every artist who came after him. Before Dante, hell was often just a vague, dark pit. After him? It was a structured, bureaucratic nightmare with nine specific circles.

Sandro Botticelli—yeah, the guy who painted the beautiful Birth of Venus—went absolutely ham on Dante’s vision. He spent years working on the Map of Hell. It’s this massive, funnel-shaped diagram that looks like a geological cross-section of a nightmare. It’s dense. It’s terrifying. It’s also incredibly precise. When you look at it, you realize he wasn't just painting a "scary place." He was trying to map out a logical system of punishment.

Then there’s Gustave Doré. If you’ve ever seen a black-and-white engraving of a guy looking sad in a dark cave, it’s probably a Doré. His 19th-century illustrations of Dante are arguably the most famous versions ever made. He mastered the use of shadow. His hell feels vast and lonely. It’s less about "fire" and more about the crushing weight of being in a place where God isn't.

📖 Related: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

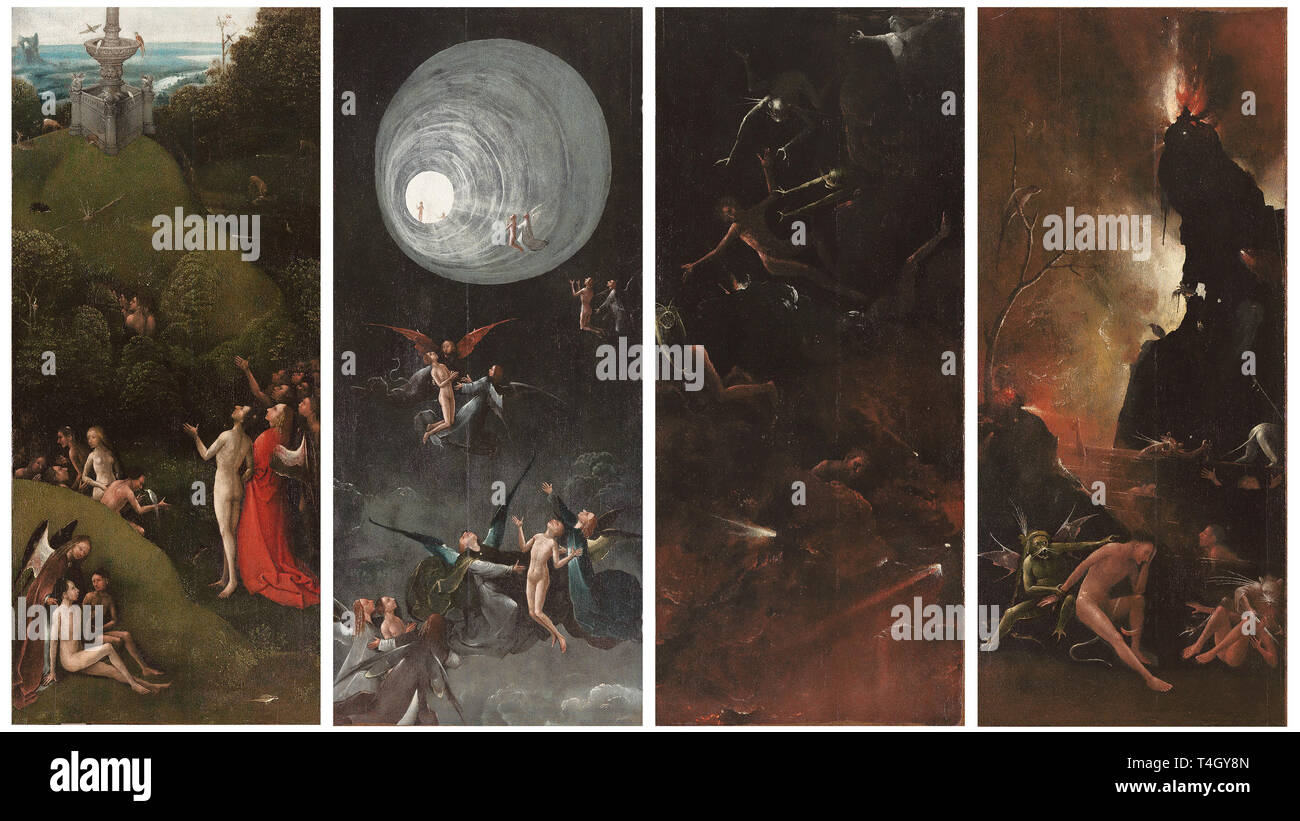

Hieronymus Bosch and the Surrealist Nightmare

If Dante provided the map, Hieronymus Bosch provided the monsters. The Garden of Earthly Delights is a triptych that everyone should see at least once, but the right-hand panel—the "Hell" panel—is where things get truly weird.

It’s not just fire and brimstone. Bosch’s hell is filled with musical instruments being used as torture devices. There’s a "Bird-Monster" sitting on a high chair eating people and then, well, excreting them into a pit. It’s bizarre. It’s chaotic. It feels like a bad acid trip from the year 1500.

What’s interesting about Bosch is how he moved away from the "organized" hell of the Italians. His vision is a total breakdown of order. He uses everyday objects—knives, skates, harps—and turns them into something sinister. It’s a very modern kind of horror. It suggests that hell isn't some far-off dimension, but a corruption of the world we already live in.

The Shift to the Internal Abyss

By the time we get to the 19th and 20th centuries, artistic depictions of hell started to change. It wasn't always a physical place underground anymore. Artists like Francis Bacon or Francisco Goya started painting hell as a state of mind.

👉 See also: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

Goya’s Black Paintings, which he painted directly onto the walls of his house while he was going deaf and losing his mind, are basically hell on earth. Look at Saturn Devouring His Son. It’s raw. It’s visceral. There’s no devil with a pitchfork there, just the horrific reality of time and destruction.

Modern art takes this even further. We see hell in the distorted, screaming faces of Bacon’s popes. We see it in the clinical, cold installations of Damien Hirst. Today, the "artistic depiction of hell" is often just a reflection of the evening news or the inside of a depressive episode.

Why We Still Care About These Images

People ask why we’re still so fascinated by this. Why do we keep buying tickets to see Bosch or Dante-inspired exhibits?

- Justice. There’s a deep human desire to see "bad people" get what’s coming to them. Artistic depictions of hell provide a visual satisfaction that the real world often denies us.

- The Aesthetic of Chaos. Let’s be real: monsters are cooler than angels. From a purely visual standpoint, the textures of scales, fire, and distorted bodies offer more for an artist to play with than the uniform perfection of paradise.

- Catharsis. Looking at a painting of hell lets us process our fears from a safe distance. You can stare into the abyss and then go get a latte in the museum café. It’s a way to flirt with the darkness without falling in.

Understanding the Visual Language

When you’re looking at these works, keep an eye out for recurring symbols. They aren't random.

✨ Don't miss: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

- Ice: People think hell is always hot. But in the oldest depictions, including Dante’s, the very center of hell is a frozen lake (Cocytus). This represents the ultimate coldness of betrayal.

- The Mouth of Hell: Common in medieval art, this shows hell as a literal beast’s mouth (the Leviathan) swallowing sinners. It’s a visceral way of saying "you are being consumed."

- Upside-down imagery: In many Renaissance pieces, sinners are depicted upside down. This symbolizes the "inversion" of the natural order.

Putting This Knowledge to Use

If you’re interested in diving deeper into the history of the macabre, don't just stick to the famous stuff.

Go look at the Doom Paintings in old English parish churches. These were murals painted for illiterate peasants to show them exactly what would happen if they stole a pig or skipped mass. They’re often crude, but they have an amazing, folk-art energy that feels very "real."

Also, check out the influence of these classical images on modern media. You can see Bosch’s DNA in movies like Pan’s Labyrinth or even the creature designs in Silent Hill. The "hell" of 14th-century Italy is still the "hell" of 21st-century gaming.

To really appreciate these works, try viewing them chronologically. Start with a 12th-century mosaic, move to a Botticelli map, then a Bosch nightmare, and finish with a modern Francis Bacon. You’ll see the evolution of human fear. It’s a wild ride.

Next Steps for the Aspiring Art Historian:

- Visit a "Doom" Painting: If you're ever in the UK, the one at St. Thomas's Church in Salisbury is one of the best-preserved examples of medieval "scare tactics."

- Compare and Contrast: Take a high-res look at Bosch’s Hell next to a scene from a modern horror film. You’ll be shocked at how many visual tropes are exactly the same.

- Read the Source Material: Pick up a copy of The Inferno with the Doré illustrations. Seeing the words and the images together is the only way to get the full, intended effect.