He’s everywhere. Honestly, if you walk into any bookstore or scroll through a streaming service for more than five minutes, you’re going to hit a deerstalker hat. It’s been well over a century since Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes first appeared in the pages of Beeton’s Christmas Annual, yet the character remains the most portrayed human literary figure in history. It’s kinda wild when you think about it. We’re talking about a Victorian-era detective who uses "elementary" logic—though he never actually says "Elementary, my dear Watson" in the original canon—and lives on a diet of tobacco and 7% cocaine solutions.

Why do we care?

Maybe it's the fact that Doyle wasn't even a full-time writer when he started. He was a doctor. A struggling one at that. While waiting for patients who never showed up at his practice in Southsea, he began sketching out a "consulting detective" based on his real-life professor, Dr. Joseph Bell. Bell could look at a man and tell he was a recently discharged non-commissioned officer from a Highland regiment who had served in India just by the way he walked and the tan on his wrists. That’s the spark. That’s where the magic of Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes began. It wasn't about ghosts or magic; it was about the terrifying, wonderful power of noticing things that everyone else misses.

The Man Who Tried to Kill His Own Creation

Doyle actually hated Holmes. Well, maybe "hate" is a strong word, but he definitely felt stifled by him. He wanted to be remembered for his "serious" work—historical novels like The White Company or Micah Clarke. He viewed the detective stories as "lower" literature, a sort of commercial necessity to pay the bills while he pursued his true passion for history and, later, spiritualism.

In 1893, he finally snapped.

In "The Final Problem," Doyle had Holmes and his arch-nemesis, Professor Moriarty, tumble over the Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland. Death. Done. End of story. He wrote in his diary that he felt "liberated." But the public? They went absolutely nuclear. Legend has it that Londoners wore black armbands in mourning. Thousands of people canceled their subscriptions to The Strand Magazine. Doyle’s own mother reportedly told him he was a fool for doing it.

✨ Don't miss: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

It took nearly a decade, and a massive amount of money from publishers, for him to bring the detective back. First, he did it through a "prequel" with The Hound of the Baskervilles in 1901, and then he officially resurrected him in "The Adventure of the Empty House." It turns out Holmes didn't fall; he used "baritsu"—a misspelled version of the real martial art Bartitsu—to throw Moriarty over the edge while he escaped. It was the original "fandom" victory.

The Joseph Bell Connection: Real Science in Fiction

You can’t talk about Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes without talking about the evolution of forensic science. Before Holmes, detectives in fiction usually relied on luck, coincidence, or "gut feelings." Holmes changed the game. He introduced the idea of analyzing bloodstains, fingerprints, and even the specific ash left behind by 140 varieties of pipe, cigar, and cigarette tobacco.

Dr. Edmond Locard, a pioneer in forensic science known for "Locard's Exchange Principle," actually encouraged his students to read Doyle's stories. This wasn't just entertainment; it was a blueprint.

Think about the sheer detail Doyle poured into the methods:

- Footprint Analysis: In A Study in Scarlet, Holmes identifies the height of a murderer based on the length of his stride in the mud.

- Toxicology: Doyle’s medical background allowed him to use poisons like alkaloids (think The Sign of Four) with a level of accuracy that baffled contemporary police.

- Document Analysis: Using typewriter wear and tear to identify a specific machine long before this was a standard FBI tactic.

It’s easy to forget that when Doyle was writing, the London Metropolitan Police (Scotland Yard) was still in its infancy. They were struggling with the Jack the Ripper case right around the time Holmes was becoming a household name. The public saw the Yard failing and saw Holmes succeeding. This created a lasting myth: the brilliant amateur who is smarter than the bureaucracy. We still see this today in House M.D., CSI, and True Detective.

🔗 Read more: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

The Weird Side of Arthur Conan Doyle

Here’s the thing most people get wrong: they think Doyle was exactly like Holmes. He wasn't. While Holmes was the ultimate rationalist, Doyle was deeply into the occult. Later in his life, he became a devout Spiritualist, believing he could communicate with the dead.

The most famous example of this is the Cottingley Fairies. Two young girls in Yorkshire took some photos of themselves with "fairies" (which were actually just cardboard cutouts from a book). Doyle, the man who created the world’s most logical detective, believed the photos were real. He even wrote a book defending them. His friend, the great magician Harry Houdini, tried to show him how easy it was to fake these things, but Doyle wouldn't budge.

It’s a fascinating contradiction. The creator of the ultimate skeptic was a man who desperately wanted to believe in the impossible. This tension is actually what makes the stories so good. Holmes often says, "When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth." Doyle was constantly testing where that line between "improbable" and "impossible" lived.

Why 221B Baker Street Still Feels Real

The relationship between Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes is essentially the story of the first "modern" celebrity. People used to write letters to 221B Baker Street as if Holmes were a living person. Even today, the Sherlock Holmes Museum at that address receives thousands of letters from people asking for help with their problems.

The friendship with Dr. John Watson is the glue. Without Watson, Holmes is just an insufferable jerk who plays the violin at 3 AM. Watson is us. He’s the veteran, the doctor, the guy who just wants to have a nice dinner but ends up chasing a hound across a moor instead. He humanizes the "calculating machine."

💡 You might also like: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

The stories aren't just mysteries; they are portraits of a changing world. We see the smog of Victorian London, the arrival of the telegraph, the shift from horse-drawn carriages to early automobiles. Doyle captured a moment in time where the old world of superstition was being dragged into the light of the scientific age.

Common Misconceptions to Clear Up

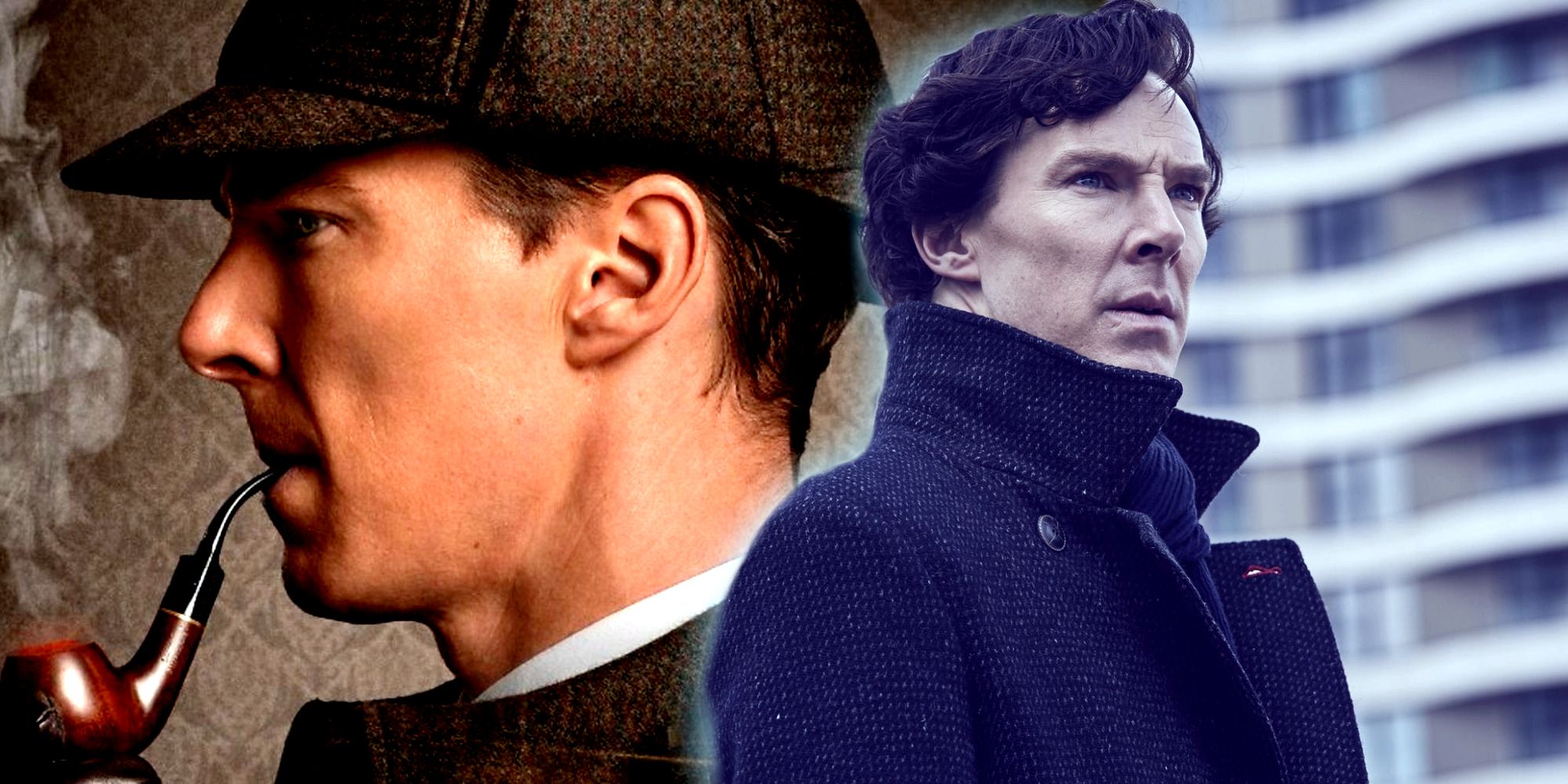

- The Deerstalker Hat: Holmes never actually wears a deerstalker in the text. That was an invention of the illustrator Sidney Paget. In the city, a gentleman like Holmes would have worn a top hat or a felt hat. A deerstalker was for the country.

- "Elementary, my dear Watson": As mentioned, he never says it in the books. The closest he gets is saying "Elementary" and "my dear Watson" in the same scene, but never as a single catchphrase. That came from the movies, specifically the 1930s films starring Basil Rathbone.

- The Pipe: Holmes smokes a variety of pipes (clay, briar, cherry wood), but the famous curved "Meerschaum" pipe was another theatrical addition. Actors used it because it was easier to rest on their chests while delivering lines than a straight pipe.

How to Read (or Re-read) the Canon

If you're looking to dive back into the world of Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes, don't just start with the first novel, A Study in Scarlet. It's actually a bit clunky and spends a weird amount of time in a flashback about Mormons in Utah.

Instead, go straight to The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes—the short stories. "A Scandal in Bohemia" introduces Irene Adler, the only woman to ever outsmart him. "The Red-Headed League" is just wonderfully bizarre. From there, jump to The Hound of the Baskervilles. It's arguably the best mystery novel ever written. It’s got atmosphere, a ghost dog, and a literal sinking bog.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Writers

- Notice the "Unnoticed": Holmes’s method is "observation, not just seeing." Spend ten minutes today in a public place (like a coffee shop) and try to deduce three things about a stranger based on their footwear or the wear patterns on their phone case. It’s harder than it looks.

- Study the "Fair Play" Mystery: If you’re a writer, study how Doyle hides clues in plain sight. He always gives the reader the information Holmes has; we just don't know how to interpret it. That's the hallmark of a great mystery.

- Visit the Sources: Check out the digitized archives of The Strand Magazine. Seeing the original Paget illustrations alongside the text changes the experience entirely. It makes the Victorian era feel much more immediate and dangerous.

- Explore the Outliers: Read The Lost World by Doyle. It has nothing to do with Holmes, but it’s where we get the "Professor Challenger" character and the blueprint for stories like Jurassic Park. It shows Doyle's range beyond the detective.

The legacy of Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes isn't just about the cases. It's about the idea that the world is a puzzle that can be solved if we just pay enough attention. It's about the comfort of knowing that even in the foggy, dark streets of a chaotic city, there's a man in a dressing room who has already figured it all out. As long as there is crime and a need for logic, there will always be a light on at 221B.