You’ve seen the diagrams. Usually, it’s a bright red tube and a slightly floppy blue one sitting side-by-side in a textbook. But if you actually look at an artery vein cross section under a microscope—I mean really get in there with a histology slide—the differences aren't just about color. They’re about structural engineering. It’s the difference between a high-pressure fire hose and a wide, low-pressure drainage pipe. Your life literally depends on these geometric variations.

The plumbing is everything.

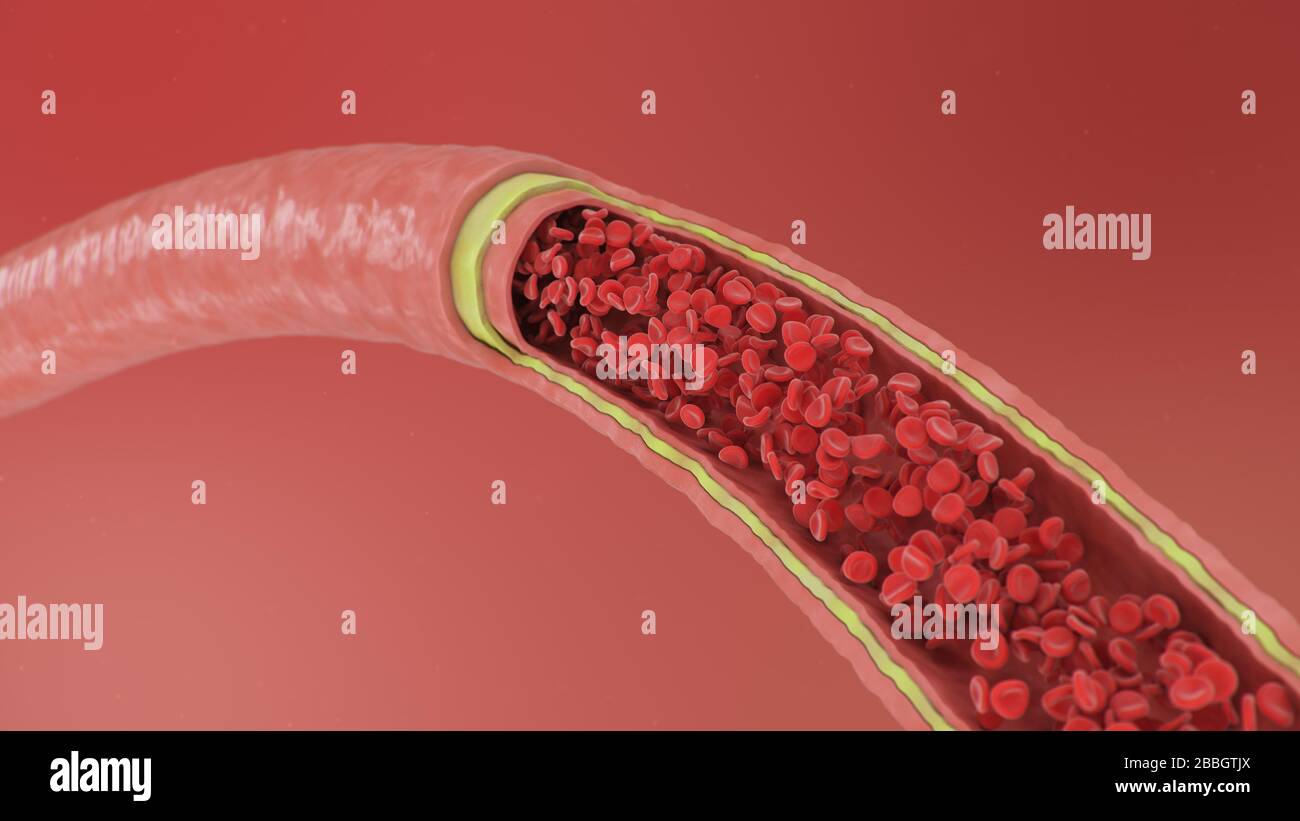

Honestly, the most striking thing about looking at these vessels in a transverse cut is the shape. Arteries are stubborn. They keep their round, circular lumen because their walls are incredibly thick and muscular. Veins? They’re the slackers of the circulatory world. Without blood pumping through them at high speed, they often collapse into irregular, pancake-like shapes. If you’re looking at a slide and see a perfect circle next to a squashed oval, you’ve found your pair.

The Three Layers You’re Actually Looking At

Every vessel, whether it’s the massive aorta or a tiny venule, follows a basic three-layer blueprint. This is the tunica system.

First, there’s the tunica intima. This is the smooth inner lining, basically a single layer of endothelial cells. It’s slicker than Teflon. It has to be, because if blood cells start snagging on the walls, you get clots. In an artery vein cross section, the intima of the artery often looks "crinkled." That’s because the elastic membrane underneath it recoils when the pressure drops, like a rubber band snapping back.

Then you hit the tunica media. This is where the real action is. In arteries, this layer is a powerhouse of smooth muscle and elastic fibers. It's thick. It’s beefy. It’s designed to handle the massive "thump" of blood coming straight from the heart. Veins have a tunica media too, but it’s thin, almost an afterthought by comparison. They don't need to withstand 120 mmHg of pressure; they’re just cruising at maybe 10 or 20 mmHg.

Finally, the tunica externa (or adventitia). This is the "sleeve" that anchors the vessel to the surrounding tissue. In veins, this is often the thickest layer. It’s mostly collagen. It keeps the vein from over-stretching and helps it stay tethered in place while you move.

Why the Elastic Lamina Matters

If you zoom in on an artery, you’ll see these distinct, wavy lines called the internal and external elastic laminae. Think of them as the "springs" in a mattress. They allow the artery to expand when the heart beats (systole) and snap back when the heart rests (diastole). Veins basically lack these. They don’t need to bounce back because they don’t get hit with that rhythmic surge.

📖 Related: High Protein Vegan Breakfasts: Why Most People Fail and How to Actually Get It Right

The Pressure Problem: Why Arteries Are Built Different

Pressure is the architect of the artery vein cross section.

Think about the physics. $P = F/A$. When the left ventricle of your heart contracts, it’s shoving a volume of blood into the system with incredible force. The arteries have to be "compliance" vessels. If they were rigid like PVC pipes, they’d burst. Instead, their cross-section reveals a massive amount of smooth muscle that can dialate or constrict. This is how your body controls blood pressure. If you're stressed, those muscles tighten, the lumen gets smaller, and pressure spikes.

Veins work on a totally different principle. They are "capacitance" vessels.

Actually, at any given moment, about 70% of your total blood volume is sitting in your veins. They’re like a reservoir. Because their walls are so thin and stretchy, they can hold a lot of blood without the pressure going up much. If you lose blood—say, from a cut—your veins constrict to "push" that reservoir back toward the heart. It’s a built-in backup system.

Valves: The One Thing Arteries Lack

If you were to take a longitudinal section rather than a cross section, you’d see one of the most important anatomical features: valves.

Arteries don't have them. They don't need them. The heart is pushing the blood so hard that it can’t really go backward. But veins? Veins are fighting gravity, especially in your legs. The blood has to crawl its way back up to your chest. To prevent it from sliding back down to your ankles, veins have bicuspid valves—little flaps of tunica intima.

When you see a "varicose vein," what you’re actually seeing is a failure of this structural geometry. The vein has stretched so much that the valves don’t meet in the middle anymore. The blood pools, the pressure rises, and the vessel becomes tortuous and visible through the skin. It’s a mechanical failure of the cross-sectional integrity.

👉 See also: Finding the Right Care at Texas Children's Pediatrics Baytown Without the Stress

Real-World Consequences of Wall Thickness

Let's talk about atherosclerosis. This is where the artery vein cross section becomes a matter of clinical urgency.

Atherosclerosis is almost exclusively an arterial disease. You don't really get "hardened veins." Why? Because the high pressure in arteries causes micro-tears in the intima. Cholesterol (specifically LDL) gets stuck in those tears. Your immune system tries to clean it up, but ends up creating a fatty plaque.

- Artery: Plaque builds up inside the thick wall, narrowing the lumen. Eventually, it can rupture, causing a heart attack.

- Vein: Because the walls are thinner and the flow is slower, they don't get these types of plaques. They get "thrombosis" (clots) instead, often from sitting too long on a plane.

It’s a different kind of failure for a different kind of pipe.

Microscopic Nuances: Not All Arteries are the Same

It’s a mistake to think every artery looks the same under a microscope. You have "elastic" arteries like the aorta, which are mostly elastic fibers, and "muscular" arteries like the ones in your arms and legs, which are mostly smooth muscle.

The aorta is basically a giant shock absorber. If you looked at its cross section, you’d see dozens of layers of elastic tissue. As you move further away from the heart, the vessels become more muscular. These are the "resistance vessels." They’re the ones that decide whether you’re sending blood to your digestive system or your biceps.

Then you have capillaries. These don't even have three layers. A capillary cross section is just a single layer of endothelial cells. That’s it. No muscle, no elastic. It’s so thin that oxygen can literally just drift through the wall. If a capillary had the wall of an artery, you’d suffocate because the oxygen would be trapped inside the "hose."

Summary of Structural Differences

If you’re trying to identify these in a lab or just trying to visualize the anatomy, keep these physical markers in mind:

✨ Don't miss: Finding the Healthiest Cranberry Juice to Drink: What Most People Get Wrong

The arterial wall is significantly thicker relative to the hole in the middle (the lumen). The lumen of an artery stays open even when empty. The tunica media is the dominant feature, packed with pink-staining smooth muscle.

The venous wall is thin, often appearing "floppy" or collapsed. The lumen is usually much larger than the lumen of the neighboring artery. The tunica externa is the most prominent layer, often blending into the surrounding connective tissue.

Making This Practical: Protecting Your Vessels

Understanding the artery vein cross section isn't just for med students. It changes how you think about your health.

Arteries fail because of pressure and "gunk." To keep those thick muscular walls healthy, you have to manage blood pressure. High pressure scars the intima. It makes the walls stiff. When an artery loses its elasticity—a process called arteriosclerosis—it can’t buffer the heart’s pulses anymore. That puts even more strain on your organs.

Veins fail because of stagnation. Since they don't have thick muscle to pump blood, they rely on your calf muscles to squeeze them. This is the "skeletal muscle pump." Every time you take a step, you’re literally squishing your veins and forcing blood upward.

Actionable Next Steps

- Move your ankles. If you’re at a desk for hours, do "toe points." This engages the muscle pump to help your thin-walled veins move blood against gravity.

- Check your "pipes." Get a blood pressure reading. If the number is high, it means your arterial walls are under constant, structural stress that will eventually change their cross-sectional shape through "remodeling."

- Hydrate for flow. Dehydration makes blood more viscous. Thicker blood is harder to push through the narrow arterial lumen and more likely to pool in the wide venous reservoir.

- Watch for "bouncing" pulses. You can feel the elastic recoil of an artery in your wrist. You can’t feel it in a vein. That "thump" is the physical evidence of the tunica media doing its job.

The geometry of your vessels is a perfect example of form following function. The artery is built for the storm; the vein is built for the storage. Keep the pressure low for the former and the movement high for the latter.