You're lying on a cold table, staring at a monitor that shows the inside of your own heart. It's weird. A decade ago, if you were having a cardiac catheterization, the doctor would almost certainly have started by numbing your groin. They’d poke a hole in your femoral artery, thread a long tube up through your torso, and do the work. But things changed. Nowadays, if you’re looking up artery access point nyt or checking recent health trends, you’ll find that the "wrist" is the new gold standard. It’s called radial access.

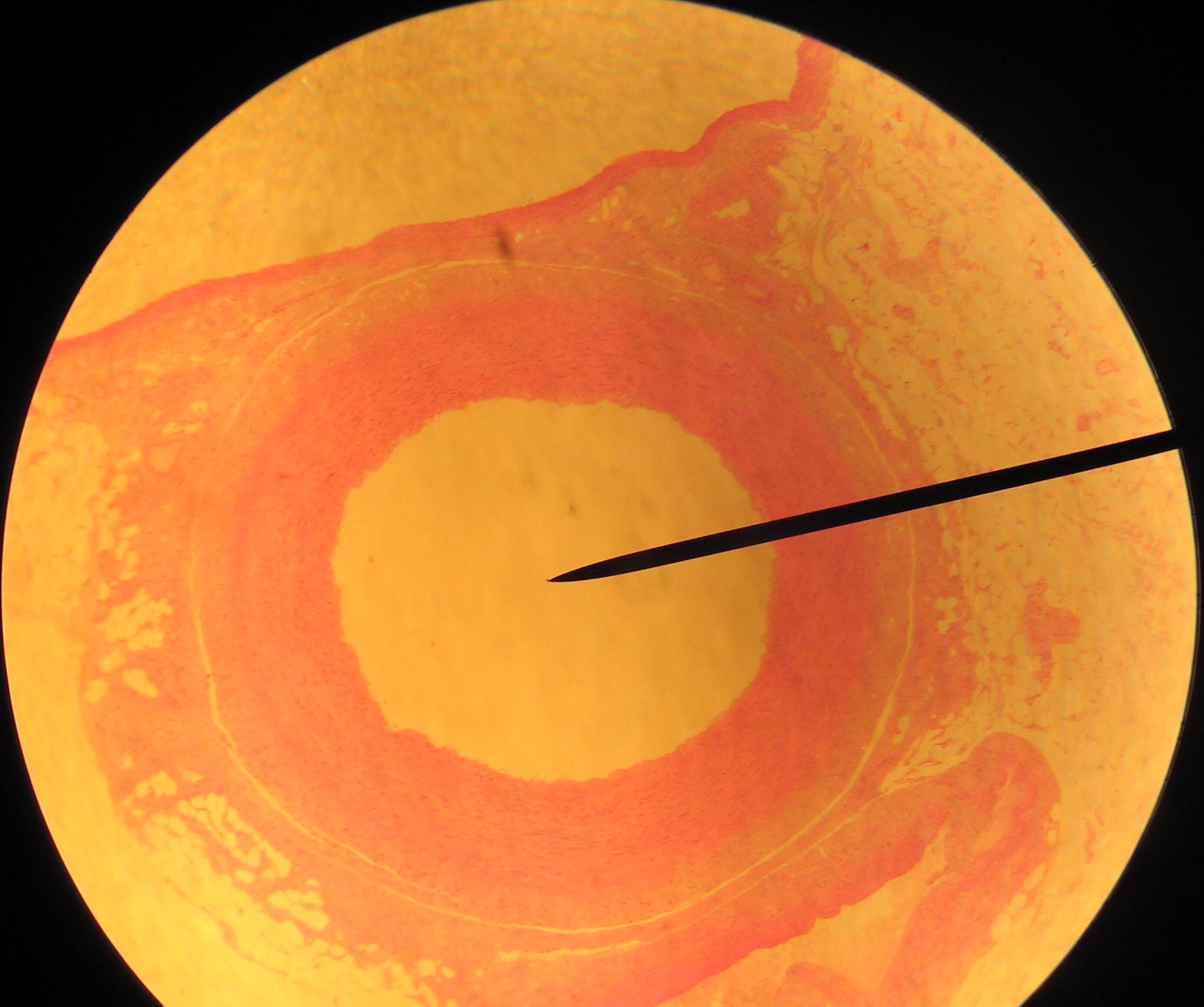

Medicine moves slowly, then all at once. For years, the femoral artery was the king of access points because it’s huge. It’s an easy target. But the femoral artery has a nasty habit of bleeding. It’s deep under the skin, tucked away near the hip, and hard to compress after a procedure. The radial artery in your wrist? That’s a different story. It’s right there. You can feel it pulsing under your skin. If it bleeds, you just press down.

The Shift in Artery Access Point Trends

The medical community didn't just wake up and decide the wrist was better for fun. It was about survival. Large-scale trials, like the MATRIX trial published in The Lancet, showed that using the radial artery instead of the femoral one actually reduced the risk of death and major bleeding in patients having a heart attack. That’s a massive deal. We aren’t just talking about a more comfortable recovery; we’re talking about staying alive.

Why does the New York Times or other major outlets keep hitting on this? Because patient preference is a powerful thing. If you’ve ever had a femoral procedure, you know the drill: you have to lie flat on your back for six hours afterward. You can't move. You can't use the bathroom. If you cough, you’re terrified the site will "pop" and you'll bleed out. With radial access, you’re basically up and walking to get a sandwich twenty minutes after the sheath comes out.

Why the Wrist Wins (Most of the Time)

The radial artery is superficial. That’s the "medicalese" way of saying it’s close to the surface. Doctors love this because it makes it incredibly easy to stop bleeding using a simple pressure band, often called a "TR Band."

Honestly, the anatomy is just smarter. The hand has a dual blood supply. You have the radial artery and the ulnar artery. If something goes wrong with the radial access point—like a rare blockage—the ulnar artery usually picks up the slack. The leg doesn't have a backup plan that’s quite as robust. If you mess up the femoral artery, you might be looking at a vascular surgeon and a long night in the OR.

💡 You might also like: How to Treat Uneven Skin Tone Without Wasting a Fortune on TikTok Trends

But it’s not always easy for the doctor

Don't get it twisted: radial access is technically harder for the cardiologist. The artery is smaller. It can spasm. Sometimes it’s "tortuous," which is a fancy word for being twisty like a mountain road. A doctor might spend ten minutes just trying to navigate a wire through a loop in your arm. Some old-school surgeons still prefer the femoral route because that’s how they were trained in the 90s, and they’re fast at it. But the data is hard to argue with.

When the Groin is Still the Go-To

There are moments when the artery access point nyt discussion has to pivot back to the leg. If you’re getting a TAVR (Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement), the equipment is just too big for your wrist. You can't fit a massive valve delivery system through a tiny radial artery. It’s like trying to fit a semi-truck through a drive-thru lane.

Also, if someone is in cardiogenic shock—their heart is literally failing and their blood pressure is tanking—the radial artery might collapse. In an emergency, a big, reliable target like the femoral artery is a literal lifesaver. It’s all about the right tool for the specific job.

The "Slender" Movement in Cardiology

There’s this sub-culture in cardiology called "Slender." These are the doctors who push the limits of what can be done through the wrist. They use thinner wires and smaller sheaths to do complex work that used to require a massive incision.

- They do complex "chronic total occlusions" (CTOs).

- They use the "distal radial" approach—the "snuffbox" on the back of your thumb.

- This keeps the main radial artery even safer.

- It allows patients to keep their arm in a more natural position during the procedure.

It's pretty wild how far it's come. We’ve gone from major surgery to "band-aid" procedures in less than a generation.

📖 Related: My eye keeps twitching for days: When to ignore it and when to actually worry

Complications No One Mentions

Nothing is perfect. Radial access has its own set of headaches. About 1% to 5% of people might experience radial artery occlusion. That means the artery closes up. Usually, you don't even feel it because the ulnar artery takes over, but it means that the doctor can't use that wrist for a future procedure.

There’s also the risk of a "hematoma" in the forearm. It looks like a nasty bruise, but if it gets big enough, it can cause "compartment syndrome," which is a true emergency. It's rare, but it's why the nursing staff is constantly checking your pulse and the tension of your wrist band after the doctor finishes.

Real-World Impact: The Patient Experience

I spoke with a nurse who’s been in the "cath lab" for twenty years. She remembers the "femoral days." She described it as a nightmare of heavy sandbags and "FemoStops"—large mechanical devices used to crush the groin area to stop bleeding. Patients were miserable.

Today? She says patients are often on their phones, texting family while the doctor is still working on their heart through their wrist. The psychological difference is night and day. You don't feel like an "invalid" when you can walk yourself to the recovery lounge.

What to Ask Your Doctor

If you or a family member is scheduled for a heart procedure, you actually have a say in this. It isn't just about what the doctor wants.

👉 See also: Ingestion of hydrogen peroxide: Why a common household hack is actually dangerous

- Ask about their "Radial First" policy. Does the hospital prioritize the wrist?

- Check their volume. How many radial procedures does this specific doctor do a year? Like anything else, practice makes perfect.

- Inquire about the "Snuffbox" approach. If you’re worried about radial artery health, see if they offer distal radial access.

- Know the backup plan. If they can't get in through the wrist, will they go to the other arm or the leg?

The Future of Access Points

We’re starting to see the same shift in other fields. Interventional radiologists are now using the wrist to treat liver tumors, fibroids, and even prostate issues. The "radial revolution" is spreading. It's becoming the default because it's safer, cheaper (shorter hospital stays), and patients flat-out prefer it.

The move away from the femoral artery is one of those quiet victories in medicine. It didn't involve a flashy new drug or a billion-dollar robot. It was just a better way to get where we needed to go.

Actionable Insights for Patients

If you are heading in for a procedure where artery access point nyt might be a factor, here is what you need to do:

- Hydrate well the day before. It makes your arteries easier to find and less likely to spasm.

- Keep your arm still. If they use the wrist, don't try to use that hand to adjust your pillows or grab your phone for at least an hour.

- Watch the site like a hawk. If you see a lump forming or your hand feels cold and numb, tell a nurse immediately. Don't wait.

- Understand the "Lie Flat" rule. If they do have to use your groin, take the "lie flat" order seriously. Tearing that artery by sitting up too soon is a mistake you only make once.

The transition from femoral to radial access is a massive win for patient safety. It’s a shift toward less invasive, more "human" medicine. While the groin still has its place for major structural work, the wrist is clearly the future for the vast majority of heart patients. Be your own advocate and ask for the radial route if it’s an option. It could save you hours of discomfort and, statistically speaking, it’s the safer bet for your heart.

Next Steps for Recovery:

After a radial procedure, avoid heavy lifting (nothing heavier than a gallon of milk) for at least 48 hours. Monitor the site for any redness, warmth, or a "pulsing" lump. If the site starts to bleed, apply firm, direct pressure and call 911 or head to the nearest ER—do not try to "wait it out." Most radial sites heal within a week, leaving nothing but a tiny freckle-sized scar.