You’ve seen the sigils. Maybe you saw them on a trendy t-shirt in a thrift shop or etched into a prop in a horror movie like Hereditary. They look cool, right? Geometric, complex, and vaguely threatening. But the reality of the Ars Goetia is a lot weirder—and frankly, a lot more tedious—than Hollywood makes it out to be.

It isn't some ancient, forbidden stone tablet found in a desert. It’s a book. Specifically, it’s the first section of a 17th-century textbook on magic called the Lemegeton, or The Lesser Key of Solomon.

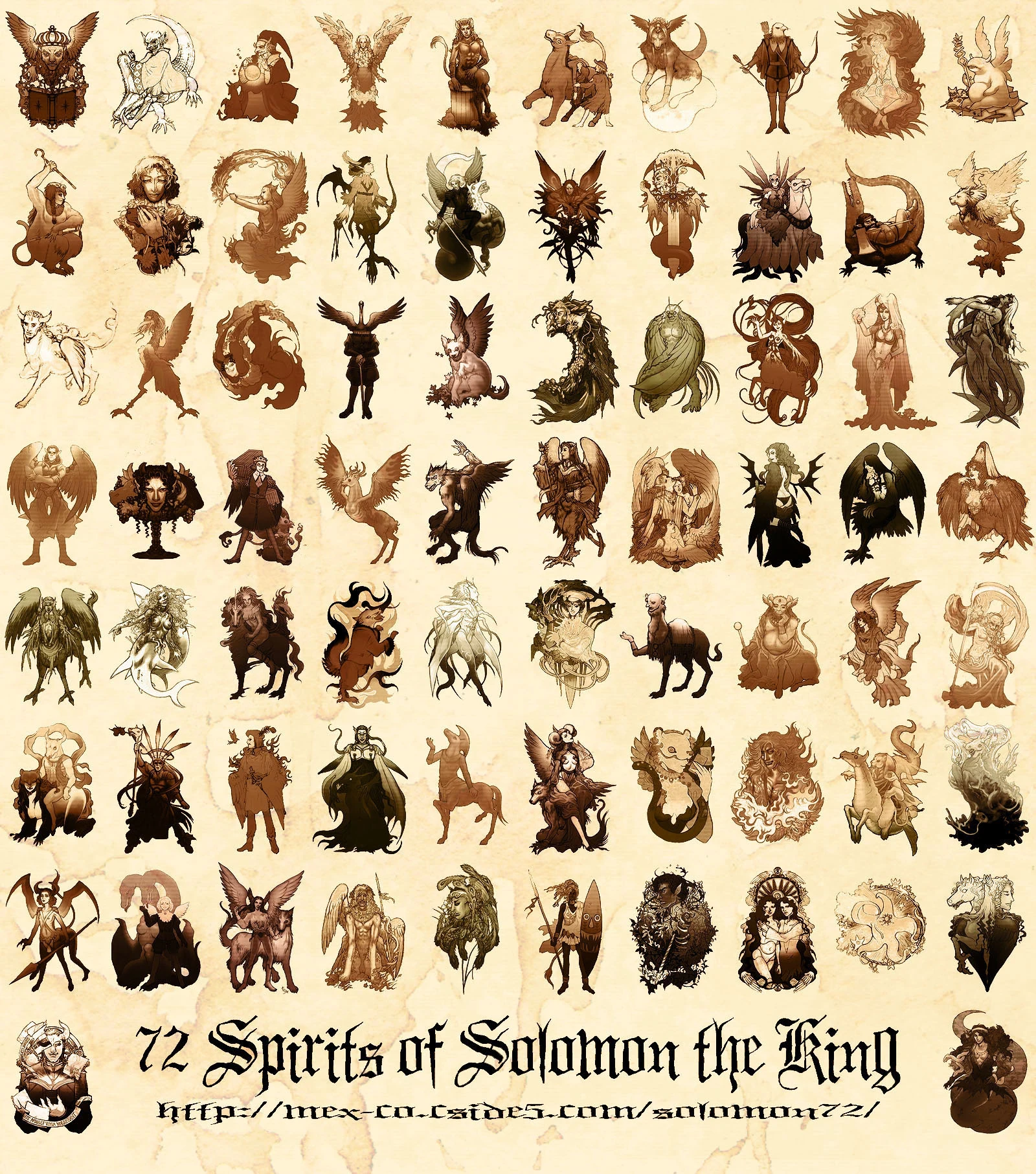

If you’re looking for a dark manual on how to sell your soul, you’re going to be disappointed. The Ars Goetia is basically a cosmic Rolodex. It lists 72 demons, their ranks, what they look like, and exactly what kind of chores they can do for you. Think of it as a demonic Yellow Pages for the Renaissance era.

Where Did This Stuff Actually Come From?

History is messy. People love to say King Solomon wrote these spells three thousand years ago to build his temple.

That’s a myth.

While the legend of Solomon controlling spirits is ancient—appearing in the Testament of Solomon as early as the 1st century—the actual text of the Ars Goetia we recognize today didn't pop up until the mid-1600s. It’s a "pseudepigraphical" work, which is just a fancy way of saying someone wrote it and put a famous dead person’s name on it to make it sell better. It’s the 17th-century version of a celebrity endorsement.

The book is a remix. It pulls heavily from Johann Weyer’s Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (1577), but it adds those iconic circular seals (sigils) that everyone obsesses over. Scholars like Joseph H. Peterson, who produced a definitive edition of the Lesser Key, have tracked these manuscripts across the British Library and the Bodleian. They weren't being used by cults in caves; they were being collected by educated men, often clergymen or academics, who were fascinated by the intersection of science, religion, and the "unseen world."

The 72 Demons: Not Just Fire and Brimstone

When you actually read the Ars Goetia, the descriptions of the spirits are bizarre. It’s a surrealist parade.

Take Buer, the tenth spirit. He’s described as appearing when the sun is in Sagittarius and is often depicted as a head surrounded by five legs, like a fleshy starfish. What’s his "evil" power? He teaches philosophy and logic. He heals "distempers" in humans. Honestly, he sounds more like a helpful, albeit terrifying, tutor than a prince of darkness.

Then there’s Stolas. He shows up as a Great Raven, but can take human form to teach you about astronomy and the properties of precious stones and herbs.

The list goes on:

- Paimon rides a dromedary and has a loud voice. He knows all the secret things of the world.

- Foras makes you invisible and helps you find lost things.

- Gaap can take a person from one kingdom to another very quickly (the 1600s version of a private jet).

The focus is surprisingly practical. These spirits are "kings," "dukes," "marquises," and "presidents." The hierarchy mirrors the European feudal system of the time. It’s as if the authors couldn't imagine a spiritual world that wasn't organized exactly like a royal court.

The Ritual: Why It’s Actually Exhausting

Modern movies make summoning look easy. You light a candle, say a chant, and boom—demon in the living room.

The Ars Goetia demands way more work. It’s bureaucratic.

You need specific tools. You need a brass vessel. You need a secret seal. You need a "Lion's skin belt" (hard to find at Target) and specific robes. The magician doesn't just ask nicely; they use the names of God to coerce the spirit into a triangle drawn on the floor. The magician stays inside a protective circle. It’s a high-stakes legal negotiation.

The "Triangle of Art" is where the spirit is supposed to manifest. The idea was that you weren't "worshipping" these entities. You were a technician commanding them. This is what historians call "Solomonic Magic." It’s built on the premise that humans, through divine authority, are the bosses of the spirit world.

Why the Ars Goetia Exploded in Pop Culture

If this is just an old, dusty book, why are we still talking about it?

📖 Related: Why the Good American Family Matters More Than Ever

Aleister Crowley.

In 1904, Crowley—the "wickedest man in the world"—published his own version of the Ars Goetia with the help of S.L. MacGregor Mathers. He added some "preliminary invocations" and basically rebranded it for the modern occultist. This version became the blueprint for almost everything we see in movies and games today.

If you play Shin Megami Tensei or Genshin Impact, you’re interacting with Goetic names. Paimon, Barbatos, Morax—these aren't just cool-sounding names the developers invented. They are ripped straight from the 17th-century text.

The aesthetic of the sigils is also a huge factor. They look like "technology." They don't look like drawings of monsters; they look like circuit boards for the soul. That’s why they’ve become so iconic in the "dark academia" and "occult core" aesthetics on social media. People love the idea of a system. The Ars Goetia provides a system.

The Psychological Angle: Is It All Just in the Head?

Middle Way practitioners and modern occultists like Lon Milo DuQuette often argue that these 72 spirits aren't external monsters. They’re parts of the human psyche.

Under this view, "summoning" a spirit that teaches logic is just a ritualized way of unlocking a part of your own brain that handles logical thinking. It’s a dramatic, theatrical form of self-help. Instead of a "life coach," you have a "Duke of Hell."

Whether you believe in the literal existence of these entities or see them as Jungian archetypes, the cultural impact is the same. The Ars Goetia represents the human desire to categorize the unknown. We want to believe that if we just have the right "key" or the right "password," we can control the chaos of our lives.

Reality Check: The Dangers of the "Book"

Most of the "danger" associated with the Ars Goetia isn't about being dragged to hell. It’s about the obsession.

Serious practitioners will tell you that the book is a psychological rabbit hole. If you spend all your time worrying about whether your circle is exactly nine feet wide or if your wand is made of the right hazel wood, you’re probably losing touch with reality.

Historically, people got into real trouble with these books—not because of demons, but because of the law. Owning a grimoire in the 1600s could get you charged with witchcraft or heresy. Today, the "danger" is mostly to your wallet, as "occult experts" try to sell you "authentic" $500 brass vessels.

Actionable Steps for the Curious

If you actually want to explore the Ars Goetia without getting lost in the "spooky" hype, here is the smart way to do it.

- Read the Academic Texts First. Skip the "Witchy" blogs for a second. Read Joseph H. Peterson’s The Lesser Key of Solomon. It’s a masterpiece of historical footnoting. You’ll see exactly where the text was copied, where errors were made, and what it actually meant to the people who wrote it.

- Compare the Spirits. Look at Johann Weyer’s Pseudomonarchia Daemonum alongside the Ars Goetia. It’s fascinating to see how the list of spirits changed over just 100 years. Some spirits got "promoted," others disappeared entirely.

- Study the Art. Look at the sigils as a form of sacred geometry. Regardless of their "power," they are significant pieces of Western art history. They influenced everything from 20th-century surrealism to modern graphic design.

- Understand the Context. Realize that the authors were often devoutly religious. They weren't trying to be "anti-Christian"; they were trying to explore the full spectrum of what they believed was God’s creation.

The Ars Goetia is a mirror. It reflects the fears, hierarchies, and scientific ambitions of the 17th century. It’s a catalog of human curiosity. Whether you see it as a historical curiosity or a spiritual tool, it remains one of the most influential "forbidden" books ever compiled. Just don't expect it to do your homework for you—unless you happen to find a Great Raven who knows his way around a telescope.