Honestly, if you tried to make Around the World in Eighty Days today, the studio accountants would probably have a collective heart attack before the first frame was even shot. It’s one of those weird, massive relics of Hollywood’s "Golden Age" that feels both impossibly charming and completely insane. At the center of it all is David Niven, looking like he was born in a tuxedo, playing the most "English" English man to ever grace the screen: Phileas Fogg.

You’ve likely seen the posters or heard the theme music. Maybe you remember the hot air balloon—which, fun fact, isn't even in the original Jules Verne book. But the 1956 film version of Around the World in Eighty Days starring David Niven wasn't just a movie; it was a hostile takeover of the global box office by a man named Mike Todd.

Todd was a Broadway showman who didn't care about "budgets" or "restraint." He wanted to cram the entire planet into a 70mm frame. And he did. It’s got thousands of animals, dozens of countries, and a cast list that looks like a phone book of 1950s royalty.

The Man Who Was Phileas Fogg

When Mike Todd was looking for his lead, he didn't have to look far. David Niven was basically Phileas Fogg in real life, minus the obsessive-compulsive need to count his footsteps. Niven was suave, a bit cheeky, and possessed that "stiff upper lip" that made the wager at the Reform Club feel like a matter of life and death rather than just a bored rich guy’s whim.

The story goes that when Todd offered him the role, Niven was so desperate to play Fogg—a character he’d loved since childhood—that he told Todd he’d do it for nothing.

Todd, being a promoter to his core, reportedly replied, "You've got a deal."

Niven didn't actually work for free, of course, but that enthusiasm translated onto the screen. His performance is the glue. Without Niven’s precise, understated reactions, the movie would just be a very expensive travelogue. He balances the high-energy slapstick of Cantinflas (playing the valet, Passepartout) with a calm that suggests the British Empire might collapse if he’s two minutes late for tea.

📖 Related: Howie Mandel Cupcake Picture: What Really Happened With That Viral Post

A Production That Nearly Broke Everything

This wasn't a "sit in a studio and use a green screen" kind of shoot. In 1956, if you wanted to show the Himalayas, you went to the Himalayas.

The logistics were a nightmare. We’re talking:

- 112 exterior locations.

- 13 different countries.

- Over 68,000 extras (though some say that’s a bit of Hollywood "math").

- A menagerie of 7,959 animals, including ostriches, skunks, and a sacred cow.

Mike Todd was constantly running out of money. He was a "neophyte" producer who had never made a movie before, and he was using a brand-new wide-screen process called Todd-AO. It was high-risk. High-stakes. People thought he was crazy. At one point, the budget doubled to $6 million, which was a fortune back then.

He didn't care. He bribed people with Cadillacs. He borrowed a 165-foot royal barge from the King of Thailand. He even talked the Nawab of Pritam Pasha in Pakistan into lending him a private herd of elephants. It was pure, unadulterated hubris, and somehow, it worked.

The Invention of the "Cameo"

Before Around the World in Eighty Days, having a huge star show up for 30 seconds was just called "a small part." Mike Todd rebranded it. He called them "cameos."

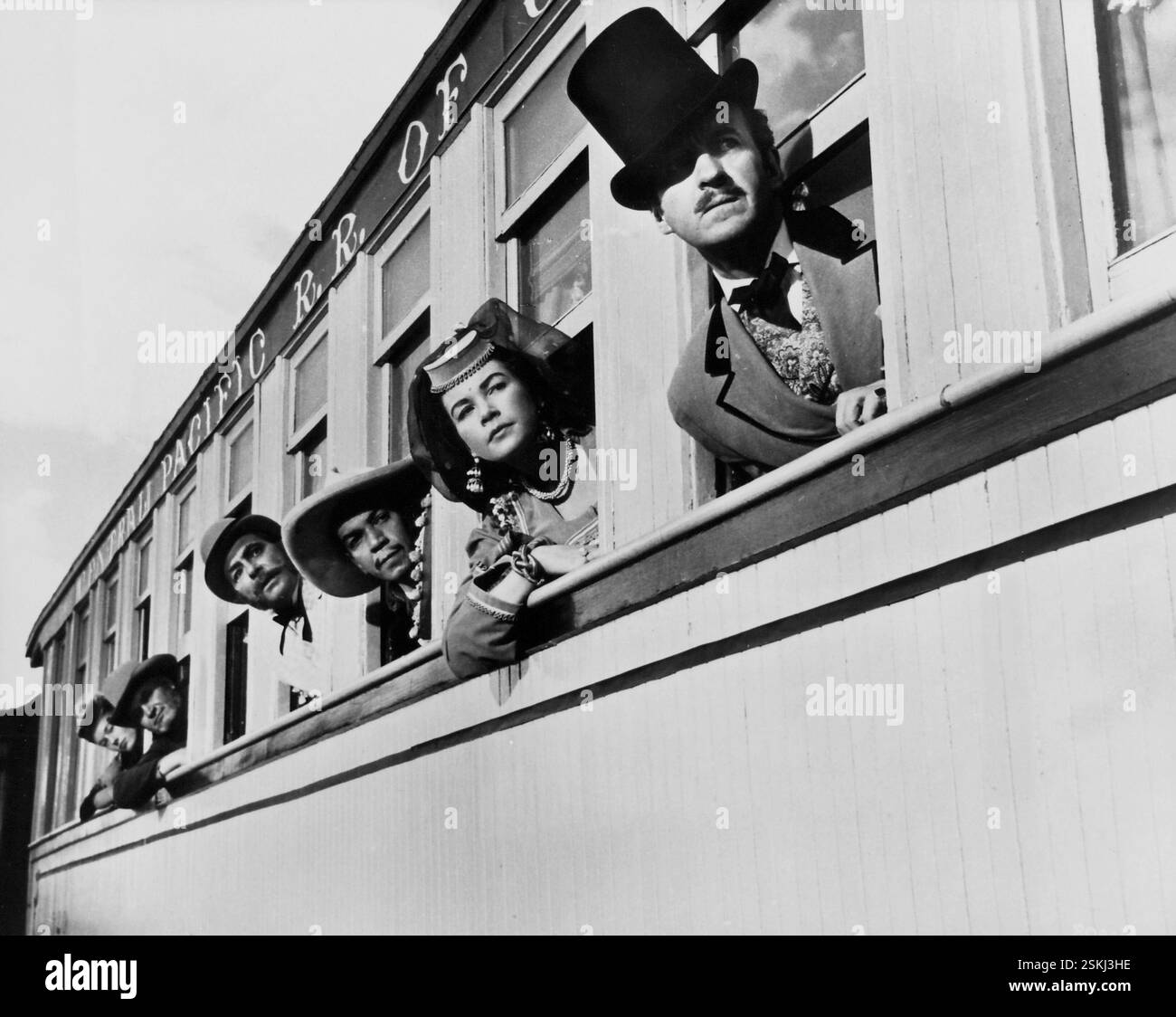

He managed to convince the biggest names in the world to show up for essentially nothing. You’ve got Frank Sinatra playing a piano in a Barbary Coast saloon. Marlene Dietrich is a saloon hostess. Sir John Gielgud plays a sacked butler. Even Buster Keaton shows up as a train conductor.

👉 See also: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

The audience would literally sit in the theater and play "spot the star." It was the 1950s version of looking for Easter eggs in a Marvel movie.

Why the 1956 Version Wins (and Fails)

It’s easy to pick on this movie now. It’s long. Like, nearly three hours long. And it’s got a "prologue" featuring Edward R. Murrow that feels like a history lecture you didn't sign up for.

Then there’s the casting of Shirley MacLaine as an Indian Princess.

Yeah. That hasn't aged well.

At the time, MacLaine was a newcomer with only two films under her belt. Casting her as Princess Aouda is a classic example of 1950s Hollywood "logic" that feels jarringly out of place today. Despite that, the chemistry between the trio—Niven, Cantinflas, and MacLaine—is surprisingly sweet.

Cantinflas, by the way, was a massive star in Mexico—bigger than Niven in many markets. In Spanish-speaking countries, he was actually billed as the lead. He brought a physical comedy to the role of Passepartout that kept the movie from becoming too stuffy. The bullfighting scene? That was added specifically to showcase his real-life skills as a comic matador. It’s not in the book, but it’s one of the most famous parts of the film.

✨ Don't miss: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

The Oscar Sweep Nobody Expected

When the 29th Academy Awards rolled around in 1957, Around the World in Eighty Days didn't just participate. It dominated.

It walked away with Best Picture, beating out heavy hitters like The Ten Commandments and Giant. It also snagged wins for:

- Best Adapted Screenplay (S.J. Perelman and crew)

- Best Cinematography

- Best Film Editing

- Best Music Score (Victor Young’s iconic waltz)

It was a validation of Todd’s "event cinema." It proved that if you make something big enough, colorful enough, and fill it with enough celebrities, the world will show up. And they did. The film grossed tens of millions, a staggering amount for the era.

The David Niven Legacy

For many, David Niven is Phileas Fogg. While Pierce Brosnan and Steve Coogan have taken stabs at the character in later adaptations, they always seem to be chasing Niven’s shadow. He captured that specific Victorian blend of arrogance and honor.

When you watch him standing in the basket of that (historically inaccurate) balloon, toast in hand, drifting over the Alps, you’re seeing the peak of mid-century escapism.

What you should do next if you want to experience this era of film:

- Watch the Saul Bass Titles: Even if you don't have three hours for the whole movie, find the ending credits on YouTube. Created by the legendary Saul Bass, they are a six-minute animated masterpiece that summarizes the entire journey.

- Compare the Book: Read the original Jules Verne novel. You’ll be surprised to find there is no balloon. The movie actually borrowed that detail from a different Verne story, but it became so iconic that everyone assumes it was always there.

- Check out "The Moon's a Balloon": If you like Niven, read his autobiography. He’s one of the best storytellers Hollywood ever produced, and his behind-the-scenes tales of 1950s sets are often better than the movies themselves.

The film is a time capsule. It’s a snapshot of a world that was just starting to feel "small" thanks to air travel, but still felt vast and mysterious enough to warrant a three-hour epic. It’s messy, it’s beautiful, and it’s quintessentially David Niven.