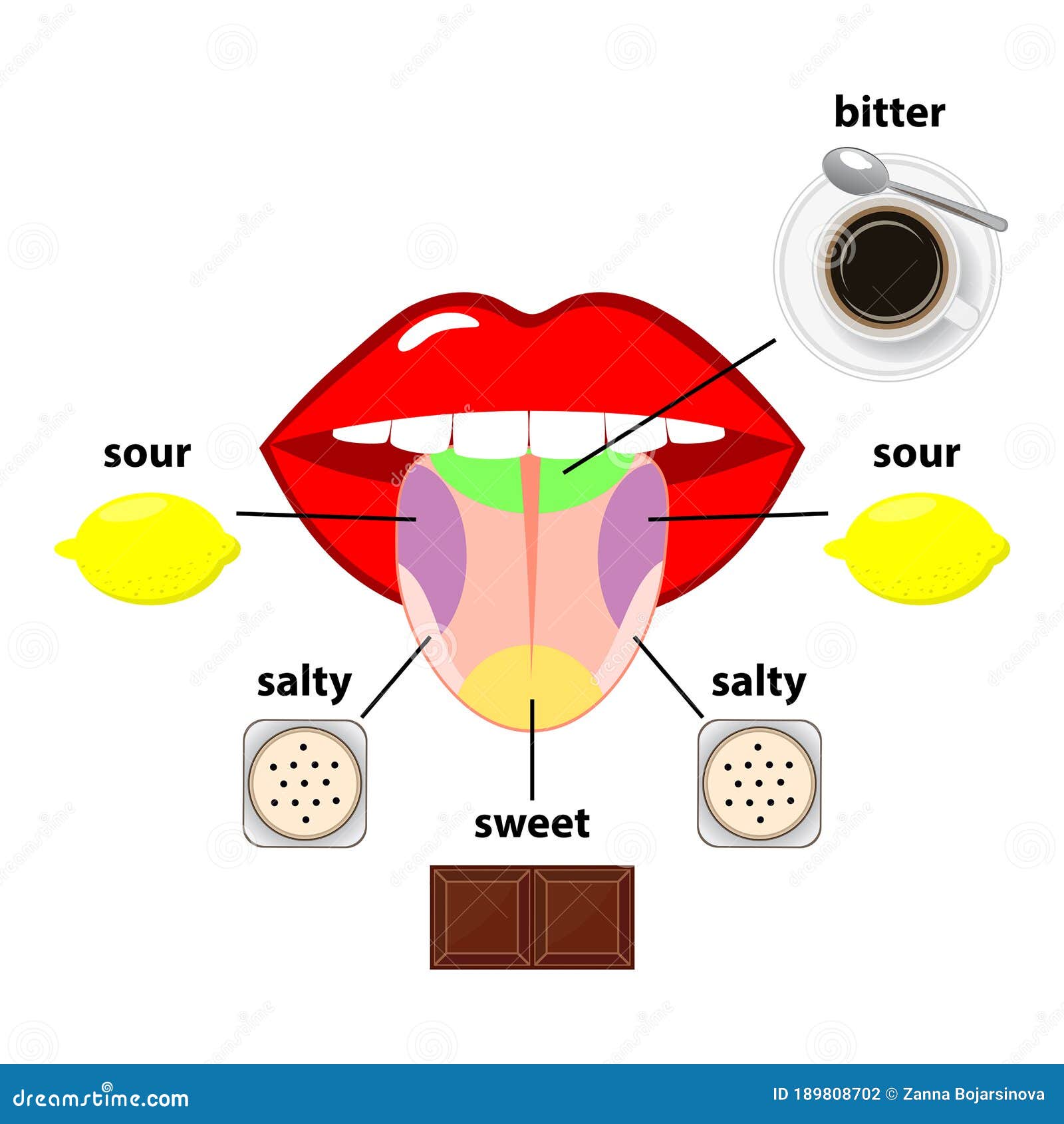

You probably remember that colored map from your third-grade science textbook. It was simple. It was clean. It showed bitter at the back, sweet at the tip, and salty and sour hugging the sides. It also happens to be a total myth.

Actually, it’s worse than a myth; it’s a century-long misunderstanding that somehow became gospel. If you’ve ever wondered why you can still taste the bitterness of a dark coffee on the tip of your tongue, it’s because those specific areas of the tongue for taste don’t actually exist in separate silos. Your entire tongue is a sensory powerhouse. Every part of it can detect every flavor.

The 1901 Mistake That Stuck

We can blame a German scientist named David P. Hänig for this mess. Back in 1901, he published a paper called Zur Psychophysik des Geschmackssinnes. He was trying to measure the thresholds of sensitivity for different tastes across the tongue. He found tiny variations. Some spots were slightly more sensitive to certain flavors than others.

The problem? He mapped these tiny differences on a graph.

Decades later, a psychologist named Edwin G. Boring (yes, that was his name) took that data and misinterpreted it. He drew a map that made it look like those areas were the only places those tastes could be detected. That single illustration basically infected the global education system for the next eighty years. It’s a classic example of how a "fact" can be born from a bad translation and a simplified diagram.

Biology is messy. It doesn’t like boxes.

How Taste Really Works (The Molecular Version)

Forget the map. Think of your tongue like a high-definition sensor array. You have thousands of tiny bumps called papillae. Most people call these taste buds, but that's not quite right. The papillae are the bumps you see in the mirror; the taste buds are tucked inside them, like orange segments inside a peel.

Inside those buds are gustatory receptor cells.

💡 You might also like: How Much Should a 5 7 Man Weigh? The Honest Truth About BMI and Body Composition

When you take a bite of a street taco, the chemicals in the food dissolve in your saliva. They swim into the pores of the taste buds and bind to these receptors. This is where the magic happens. Your brain doesn't get a signal that says "Front left corner: Sour." Instead, it gets a massive, integrated wave of data from across the entire surface.

The Five (or Six?) Players

We used to talk about the Big Four: Sweet, Sour, Salty, Bitter. Then, umami—that savory, brothy hit you get from MSG, parmesan cheese, or sun-dried tomatoes—finally got its seat at the table in the early 2000s.

But science is moving faster now. Researchers like Dr. Richard Mattes at Purdue University have been pushing for a sixth taste: oleogustus. That’s basically the taste of fat. It’s not just a texture or a "mouthfeel." There’s evidence we have specific receptors for long-chain fatty acids. If you’ve ever tasted oil that’s gone rancid, you’ve experienced the "taste" of fat without the pleasant aroma. It's distinct. It’s chemical. It’s real.

Why Some Spots Feel Different

Even though the "map" is fake, your tongue isn't perfectly uniform. It's just more nuanced than a textbook diagram.

The back of your tongue, specifically near the circumvallate papillae (those big bumps in a V-shape), is indeed more sensitive to bitterness. This is an evolutionary survival tactic. Most poisons in nature are alkaloids, which taste bitter. Having a "tripwire" for bitterness at the very back of the throat gives your body one last chance to gag or vomit before you swallow something lethal.

It’s a "better safe than sorry" design.

Conversely, the tip of your tongue has a high concentration of fungiform papillae. These are loaded with receptors. While they can taste everything, they are your primary "interface" with food. Because it's the first part of the tongue that touches a meal, it’s highly sensitive to everything from temperature to texture to the basic chemical makeup of your dinner.

📖 Related: How do you play with your boobs? A Guide to Self-Touch and Sensitivity

The Role of the Soft Palate (The Tongue's Secret Partner)

If you really want to debunk the areas of the tongue for taste theory, look at the roof of your mouth.

You actually have taste buds on your soft palate and even in your epiglottis. If the "map" were true, the roof of your mouth would be a flavorless desert. But it’s not. If you’ve ever burnt the roof of your mouth on a slice of pizza, you know that area is incredibly sensitive. It contributes to the overall "profile" of what you're eating.

Then there’s the nose. Roughly 80% of what we perceive as "flavor" is actually aroma. Taste is just the chemical signals of sweet, salty, etc. Flavor is the symphony created when those signals combine with the volatile organic compounds traveling through the back of your throat into your nasal cavity. This is "retronasal olfaction." Without it, an onion and an apple taste remarkably similar.

The Genetics of Taste

Why does your friend think cilantro tastes like soap while you love it? It’s not because their tongue map is different. It’s genetics.

The OR6A2 gene influences how you perceive aldehydes, which are found in cilantro. If you have a specific variation of that gene, your brain interprets that flavor as "Ivory Spring."

There’s also the "Supertaster" phenomenon. About 25% of the population has an unusually high number of fungiform papillae. To a supertaster, a hoppy IPA doesn't just taste "a bit bitter"—it tastes like a chemical attack. They aren't being picky eaters; their tongues are literally receiving more data than yours. Their areas of the tongue for taste are basically overclocked.

On the flip side, you have "non-tasters" who need massive amounts of spice and seasoning to feel anything at all. They’re the ones drenching everything in ghost pepper sauce just to feel alive.

👉 See also: How Do You Know You Have High Cortisol? The Signs Your Body Is Actually Sending You

Nuance in the Mouth

Let’s talk about the trigeminal nerve. This isn't technically "taste," but it’s part of the experience. This nerve carries signals for "chemesthesis"—the physical sensations triggered by chemicals.

- Menthol: Feels cold because it triggers the same receptors that detect actual freezing temperatures.

- Capsaicin: Feels hot because it tricks your brain into thinking your mouth is literally on fire.

- Carbonation: That "sting" of a cold soda is actually a mild acid burn that your brain interprets as refreshing.

None of this fits on a map. It’s a full-head experience.

Real-World Implications of the Modern View

Understanding that taste is distributed, not localized, has massive implications for healthcare.

When patients undergo radiation for head or neck cancer, their taste buds are often damaged. If the "map" were true, you could just protect one area of the tongue to save "sweetness." But because receptors are everywhere, doctors have to think about the entire oral cavity.

It also changes how we approach "flavor tripping" with things like the Miracle Berry (Synsepalum dulcificum). This fruit contains a protein called miraculin. It binds to your sweet receptors and, in the presence of acid (sourness), it changes shape and "turns on" the sweet signal. Suddenly, a lemon tastes like lemonade. This wouldn't work if the tongue were strictly partitioned; the protein needs to interact with receptors across the entire surface to create that reality-bending effect.

What You Can Do Right Now

The next time someone tells you that you taste sugar on the tip of your tongue, perform a "science experiment" right at the dinner table.

Take a tiny grain of salt. Place it on the very back of your tongue. You’ll taste it instantly.

Take a drop of lemon juice and put it right in the center. It’ll still be sour.

Better Ways to Experience Flavor

- Clean the Palate: Drink room-temperature water between different types of food to reset the receptors across the entire tongue surface.

- Aeration: Notice how wine tasters "slurp"? They’re trying to aerosolize the liquid so the aromas hit the back of the nose while the liquid hits all the receptors on the tongue and palate simultaneously.

- Temperature Matters: Extreme cold numbs your receptors. If you want to actually taste the complexity of a high-end cheese or chocolate, let it come to room temperature. A cold chocolate bar is just a "texture" bar; a room-temp one is a flavor explosion.

Stop looking for "zones." Start treating your mouth as a single, complex organ. The old map is dead. Your sense of taste is much more interesting than a third-grade drawing.