You're probably here because a geometry problem is staring you in the face and your brain feels like a browser with too many tabs open. It happens. Honestly, most people memorize a single formula in fifth grade and then never think about it again until they’re trying to calculate how much mulch to buy for a corner garden bed or helping a frustrated teenager with their homework.

The area of a triangle equation isn't just one thing. It’s a shapeshifter.

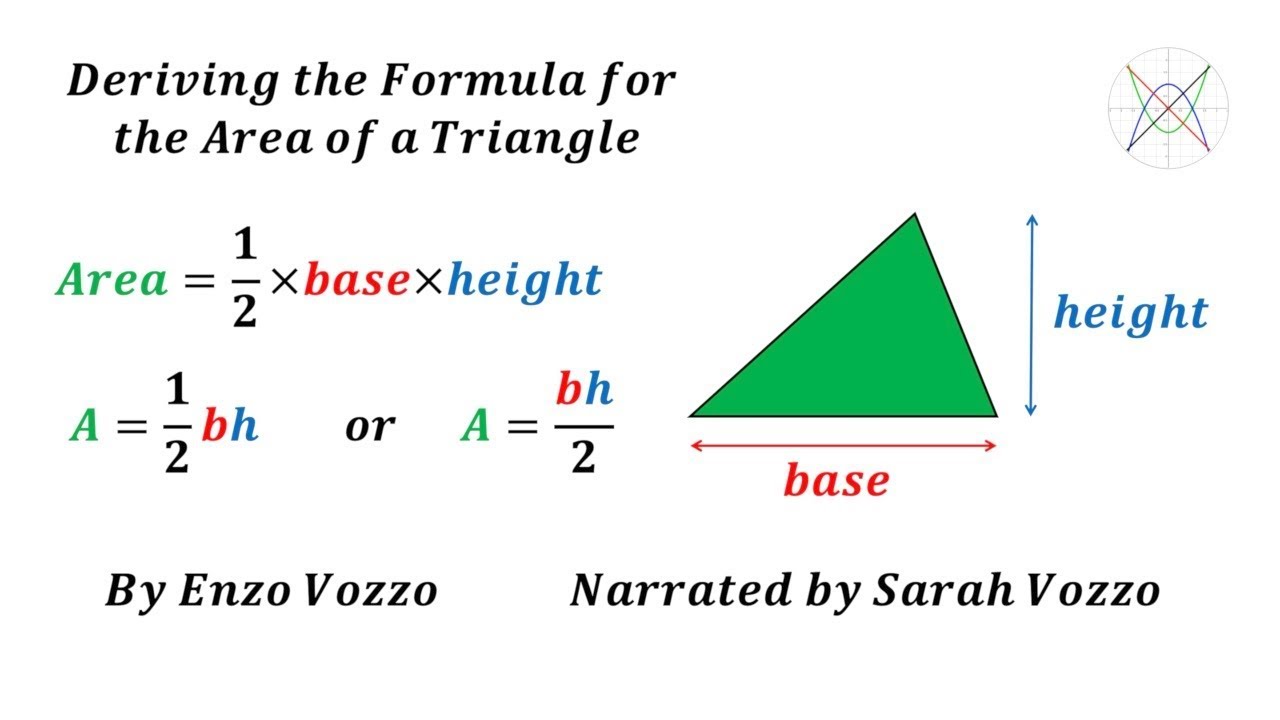

Most of us default to $A = \frac{1}{2}bh$. It’s the classic. The reliable sedan of math. But what happens when you don't know the height? What if you only have the lengths of the sides? That’s where things get messy—and interesting. Math isn't just about plugging numbers into a slot; it's about choosing the right tool for the specific mess you're trying to clean up.

The Standard Model: When Life Gives You a Base

If you have a clear horizontal base and a vertical line dropping straight from the top peak, you’re golden. This is the area of a triangle equation at its most basic.

$$A = \frac{1}{2} \times \text{base} \times \text{height}$$

Think about why that $1/2$ is even there. It’s not just a random tax the math gods take. If you take any triangle and duplicate it, then flip it and press it against the original, you usually end up with a parallelogram. Since the area of a parallelogram is just $base \times height$, the triangle—being exactly half of that shape—needs that fraction. It’s intuitive once you see it.

I’ve seen people get tripped up by "obtuse" triangles. You know the ones. They lean over like they’ve had too much coffee. In those cases, the height actually falls outside the triangle's footprint. You have to draw a dotted line out from the base just to meet the "altitude" dropping from the peak. It feels wrong, like you’re cheating by measuring space that isn't inside the shape, but the math holds up. The height is always the shortest distance from the highest point to the line containing the base. Period.

Heron’s Formula: The "No Height" Savior

Sometimes you have no idea what the height is. You have a weirdly shaped plot of land or a piece of fabric, and all you can do is run a tape measure along the three edges.

You’re stuck, right?

Not if you use Heron of Alexandria’s method. This guy lived in the first century and figured out how to find the area using only the side lengths ($a, b, c$). This is the area of a triangle equation for the real world. First, you find the "semi-perimeter" ($s$), which is just the perimeter divided by two.

$$s = \frac{a + b + c}{2}$$

Then, you plug it into this beast:

$$Area = \sqrt{s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)}$$

It looks intimidating. It’s not. It’s just subtraction and a bit of square root work. If your sides are 5, 6, and 7, your $s$ is 9. Then you’re just doing $\sqrt{9 \times 4 \times 3 \times 2}$.

When Trigonometry Crashes the Party

Now, if you’re doing construction or high-level design, you might have two sides and the angle between them. This is the "Side-Angle-Side" (SAS) scenario.

Forget the height.

You don't need to drop a plumb line if you know the sine of the angle. The formula becomes:

$$Area = \frac{1}{2}ab \sin(C)$$

Essentially, the $b \sin(C)$ part is just a fancy way of calculating the height using trigonometry. It’s the same old formula wearing a tuxedo. I’ve talked to architects who use this constantly because angles are often easier to measure with a transit than vertical heights are to eye-ball in the field.

Why the Coordinate Plane Changes Everything

For the coders and data scientists out there, triangles usually exist as three sets of coordinates: $(x_1, y_1)$, $(x_2, y_2)$, and $(x_3, y_3)$.

Don't bother measuring distances between points.

There’s a "shoelace formula" (or determinant method) that is way faster for a computer to process.

$$Area = \frac{1}{2} |x_1(y_2 - y_3) + x_2(y_3 - y_1) + x_3(y_1 - y_2)|$$

It’s called the shoelace formula because of how the coordinates cross-multiply. It’s beautiful in its efficiency. If you're building a game engine or a mapping tool, this is your bread and butter. It handles "negative" areas (which happen depending on the direction you trace the points) by taking the absolute value at the end.

Common Pitfalls (And How to Avoid Them)

People mess this up. A lot.

The biggest mistake? Mixing units. You cannot multiply a base in inches by a height in feet and expect anything other than a disaster. Your result will be in "inch-feet," which isn't a real thing anyone wants to deal with. Convert everything to a single unit before you even touch the area of a triangle equation.

Another one: The "Base" isn't always the bottom.

Gravity doesn't define geometry. You can rotate a triangle however you want. Any of the three sides can be the base. The trick is that the "height" must be perpendicular to whichever side you picked as the base. If you pick the slanted side as the base, your height is the line coming off it at a 90-degree angle.

💡 You might also like: How to Compose a Blog That Actually Gets Noticed on Google and Discover

The Special Case: Equilateral Perfection

If all your sides are the same length ($s$), you don't even need the $1/2 bh$ setup. You can use a shortcut that looks like magic but is just derived from the Pythagorean theorem:

$$Area = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{4}s^2$$

It’s fast. It’s sleek. If you’re dealing with hexagonal tiling (which is just six equilateral triangles shoved together), this is how you calculate the surface area of the whole pattern in seconds.

Real-World Nuance: It’s Rarely a Perfect Triangle

In the real world, things are "triangular-ish."

If you're measuring a sail or a roof section, the edges might have a slight curve. In those cases, these equations give you the "minimum" or "ideal" area. Professionals usually add a "waste factor" of 10% or more.

Don't treat the math as gospel if the physical object is wonky. Math assumes perfect lines. Nature rarely provides them.

Your Next Steps for Accuracy

To actually use this information without pulling your hair out, follow this workflow:

- Identify what you know: Do you have a height? If yes, use $1/2 bh$. If no, do you have three sides? Use Heron’s.

- Check your units: Ensure your base and height (or sides) are all in meters, inches, or centimeters. Don't mix.

- Draw it out: Even a rough sketch helps you visualize where the height should be. It prevents you from accidentally using a slanted side as a vertical height.

- Run the numbers twice: Calculation errors are more common than formula errors. If you're using a calculator, watch your parentheses—especially with Heron’s formula.

- Apply a "Real World" Buffer: If you're buying materials based on this area, always buy slightly more than the equation suggests to account for cuts and overlaps.