You’re standing in your garden, looking at a zucchini plant that’s producing plenty of flowers but zero actual squash. It’s frustrating. You might start wondering if you’ve got a "dud" or if, perhaps, the birds and the bees talk you got in middle school actually applies to the greenery in your backyard. So, are there male and female plants, or is botany just one big, confusing blur of green?

The short answer? Yes. But it’s also way more complicated than "boy plants" and "girl plants."

📖 Related: That Viral Stanley Cup Girl Fight: What It Says About Consumer Mania

Plants have been figuring out how to reproduce for millions of years, and honestly, they’ve come up with some pretty wild strategies that make human biology look relatively straightforward. While we tend to think of gender as a binary, plants treat it more like a flexible toolkit. Some plants are strictly one or the other, some are both at the same time, and some actually switch back and forth depending on how stressed they are or what the weather is doing.

The Three Main Ways Plants "Do" Gender

If you want to understand the botanical world, you have to get used to some slightly nerdy terminology, but it’s basically just a way to categorize who has which parts.

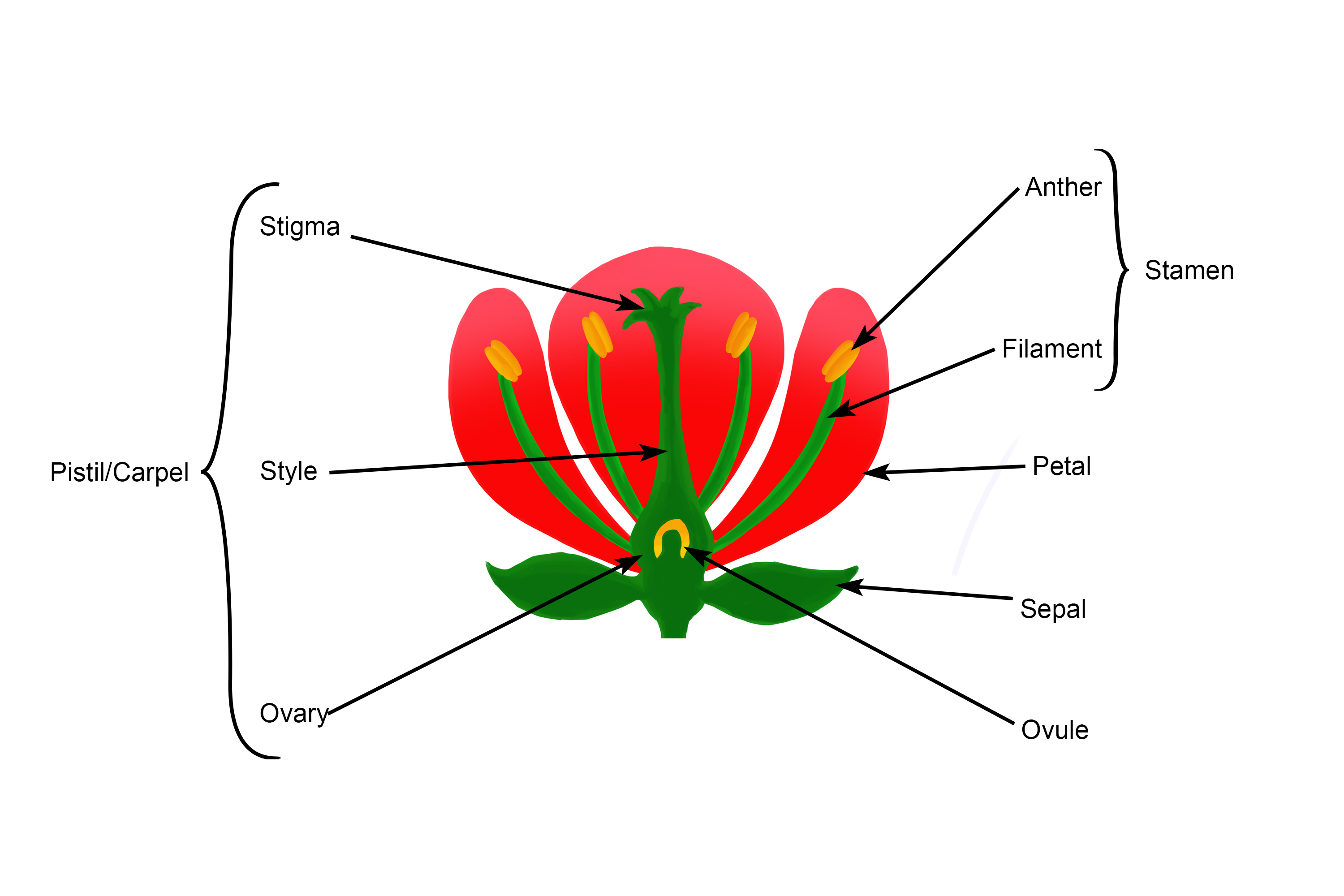

Most of the plants you see every day—about 80% of them—are what scientists call hermaphroditic or "perfect." This means a single flower contains both male parts (stamens that produce pollen) and female parts (the pistil that receives pollen). Think of lilies or roses. They’re self-contained reproductive powerhouses.

Then you have the monoecious crowd. The word literally means "one house." These plants have separate male and female flowers, but they both grow on the same individual plant. Corn is a classic example. The tassels at the very top are the male flowers shedding pollen, while the silks peeking out of the ears lower down are the female parts waiting to catch it.

Finally, we get to the dioecious plants ("two houses"). This is the direct answer to the question: are there male and female plants? In these species, an individual plant is either entirely male or entirely female. You need one of each nearby if you want any seeds or fruit. If you’ve ever wondered why your neighbor’s holly bush is covered in bright red berries while yours is just... leaves... it’s probably because you have a male plant and they have a female one.

Why Some Species Chose the Single-Gender Route

You might think it’s inefficient. Why would a plant evolve to need a partner when it could just do everything itself?

Evolutionary biologists like Dr. David Haig at Harvard have spent a lot of time looking into this. The big reason is genetic diversity. When a plant has both parts in one flower, there’s a high risk of self-pollination. Self-pollination is basically botanical inbreeding. It leads to weaker offspring that can’t handle diseases or changing climates as well. By forcing a "male" plant to send its pollen to a "female" plant, the species ensures that genes are being shuffled constantly.

It’s a survival strategy.

✨ Don't miss: Tenis de bota para mujer: Por qué tus tobillos (y tu outfit) te lo van a agradecer

Take the Ginkgo biloba tree, for instance. It’s a "living fossil" that hasn’t changed much in 200 million years. Ginkgos are strictly dioecious. If you plant a female Ginkgo, you’ll eventually get seeds that smell—honestly—like rancid butter or vomit. Because of this, most city planners only plant male Ginkgos in parks. It’s a great plan until you realize that without any female trees to "catch" the pollen, the male trees just pump out massive amounts of it, making everyone’s seasonal allergies ten times worse.

Cannabis, Hops, and the Economic Side of Plant Sex

In some industries, knowing the gender of a plant isn't just a fun fact; it's a multi-billion dollar necessity.

Take the cannabis industry. If you’re growing for THC or CBD, you only want the females. Female cannabis plants produce the resinous buds that contain the active compounds. If a male plant sneaks into the greenhouse, it will pollinate the females, causing them to stop producing resin and start producing seeds. This ruins the harvest. Growers spend an incredible amount of time "sexing" their plants early on, looking for tiny "pre-flowers" under a magnifying glass to cull the males before they can do any damage.

Hops—the stuff that makes your beer bitter and aromatic—work the same way. Only the female hop plants produce the cones used in brewing. Commercial hop yards are almost exclusively female. In fact, in some parts of the UK, it used to be a local ordinance that you couldn't grow male hop plants because they might "contaminate" the neighbors' female crops with unwanted pollen.

Can Plants Change Their Gender?

Here is where things get truly weird. Some plants aren't "stuck" with the gender they were born with. This is called sequential hermaphroditism.

The Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), a common North American woodland wildflower, is a master of the switch. When the plant is young or the soil is poor, it usually produces only male flowers. Why? Because making pollen is "cheap" in terms of energy. However, if the plant had a great year, soaked up lots of sun, and stored plenty of energy in its root (corm), it might emerge the following spring as a female. Producing seeds and fruit takes a massive amount of energy, so the plant only "decides" to be female when it can afford it. If a deer chomps on it and it loses its leaves, it might switch back to being male the next year to save resources.

It’s a tactical biological pivot.

Identifying Your Own Plants

If you’re staring at your garden wondering what’s what, here’s how you can actually tell the difference.

🔗 Read more: Why Jan 3 Matters More Than You Think

For monoecious plants like cucumbers or squash, look at the base of the flower. A female flower will have a tiny, miniature version of the fruit (a "micro-cuke" or a tiny ball) right behind the petals. This is the ovary. The male flower will just have a thin, straight stem.

For dioecious trees like Hollies, Willows, or Junipers, you usually have to wait until they bloom.

- Male flowers will have stamens covered in yellow or orange dust (pollen).

- Female flowers will have a central "sticky" looking part (the stigma) and, eventually, the fruit or seed pod.

Persimmon trees are another famous example. If you have a lone persimmon tree that never fruits, you likely have a male. Or, you have a female that is too far away from a male suitor for a bee to make the trip.

The Allergy Connection

There’s a theory in urban forestry called "botanical sexism."

Since the 1960s and 70s, many cities have prioritized planting male trees because they don't drop "messy" fruits, seeds, or pods that have to be cleaned up by street crews. While this keeps the sidewalks clean, it has created a massive spike in hay fever. We’ve turned our cities into "pollen factories" by removing the female trees that would naturally act as "pollen sinks" or filters.

Thomas Ogren, the creator of the Ogren Plant Allergy Scale (OPALS), has been a vocal critic of this practice. He argues that by bringing back female plants to our landscapes, we could significantly reduce the pollen load in the air.

What This Means for Your Garden

Understanding that there are male and female plants changes how you shop at the nursery. You can't just buy one random Kiwi vine and expect fruit. You need to buy a "pair."

When you're at the garden center:

- Check the tags for "Male" or "Female" designations on species like Sea Buckthorn, Skimmia, or Pistachio.

- Ask about "self-fertile" varieties. These are often dioecious plants that have been grafted or bred to have both parts on one plant, making life easier for home gardeners with limited space.

- Observe the pollinators. If you see bees visiting one plant but not another, take a closer look at the anatomy.

Botany is rarely a simple "yes" or "no" situation. It's a spectrum of reproductive strategies designed to keep life moving forward. Whether a plant is male, female, both, or a frequent flier between the two, it's all about the same goal: survival.

Next time you’re outside, take a magnifying glass to a flower. Look for the pollen-heavy anthers or the swollen ovaries. Once you start seeing the "gender" of the landscape around you, the natural world starts looking a lot less like a static backdrop and a lot more like a complex, living soap opera.

Actionable Next Steps:

Check any non-fruiting trees or shrubs in your yard against a dioecious species list (like Holly, Ash, or Mulberry). If you find you have a lone female plant, look for a male variety of the same species to plant within 50 feet to ensure pollination for the next season. For vegetable gardeners struggling with "blind" fruit, practice hand-pollination by taking a male flower, peeling back the petals, and dabbing the pollen directly onto the center of the female flower.