You're staring at your 401(k) portal. It’s a mess of tickers like VFIFX or SWYMX. You just want to know one thing: are target funds good for your actual life, or are they just a lazy way to lose money?

Most people treat these funds like a slow cooker. You toss in your money, set the date for when you'll be 65, and walk away. But here’s the thing—not all slow cookers are built the same. Some of them burn the meal, and some of them leave it raw in the middle.

If you’re looking for a simple yes or no, you won't find it here because the answer depends entirely on your gut for risk. Honestly, target-date funds (TDFs) are the most popular investment vehicle in America for a reason. They manage trillions. They keep people from doing stupid things when the market crashes. But they also have a "glide path" that might be way too conservative for you, or maybe even too aggressive if you plan on retiring early.

The Mechanics of the Glide Path

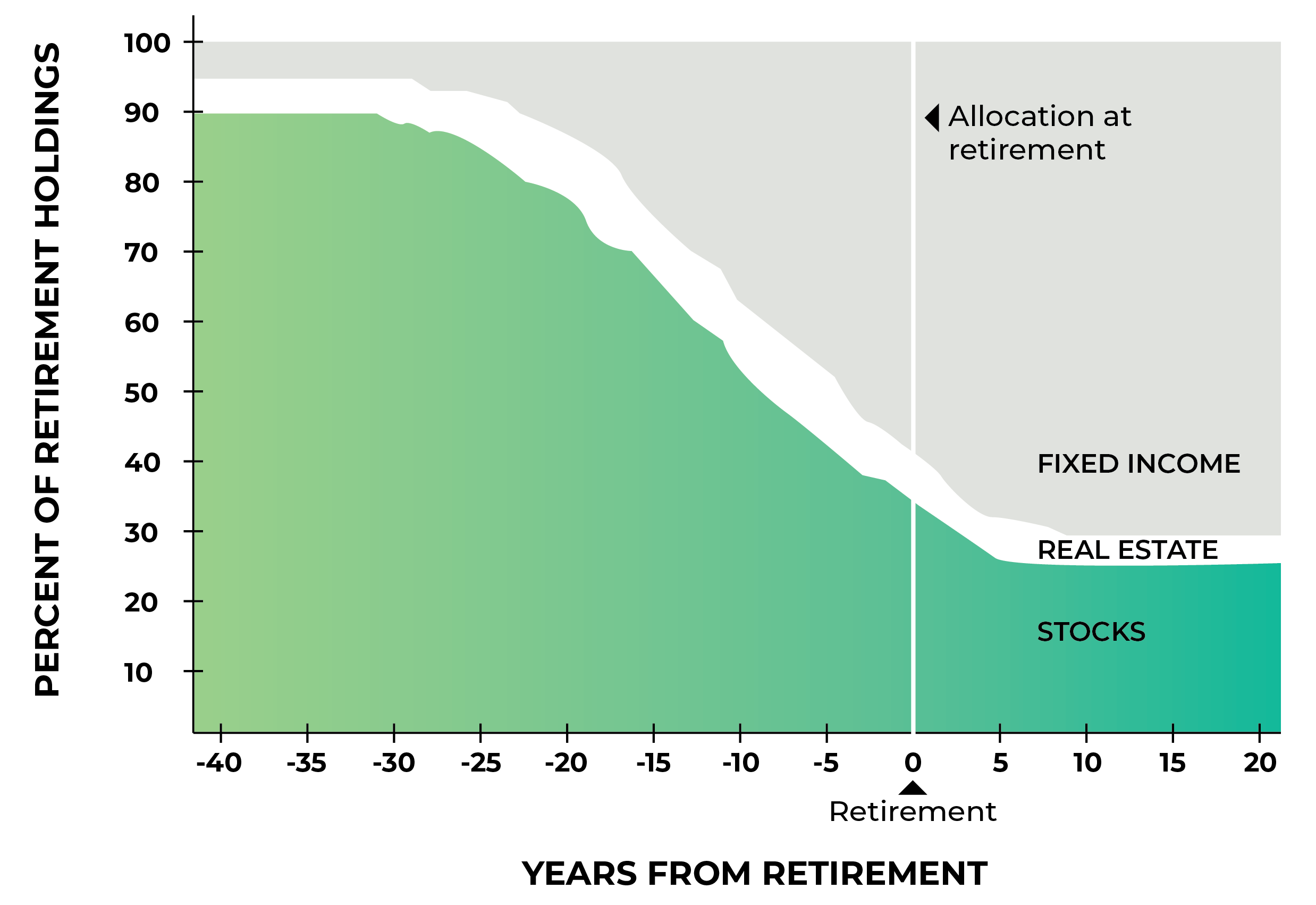

Basically, a target-date fund is a wrapper. Inside that wrapper is a mix of stocks and bonds. As you get older, the fund automatically sells stocks and buys bonds. This is the "glide path."

Think of it like an airplane landing. When you're 30, the plane is at 30,000 feet. You can handle some turbulence. The fund might be 90% stocks. But as you get closer to the runway—your retirement date—the pilot starts descending. By the time you hit "Target Date 2055," the fund might be 50% bonds to make sure a sudden market drop doesn't wipe out your ability to buy a condo in Florida.

But here is where it gets tricky. Not every fund company uses the same map. Vanguard’s glide path looks nothing like Fidelity’s.

Some funds are "to" funds, meaning they reach their most conservative point right at the year on the label. Others are "through" funds. They keep changing the mix for 15 or 20 years after you retire. If you pick a "through" fund and expect it to be safe the day you retire, you might be in for a nasty surprise if the market dips right when you need to start withdrawals.

Why the Expense Ratio Matters More Than You Think

You've gotta look at the fees. Some target-date funds are "funds of funds." They just buy other index funds. If they charge you 0.08%, that’s great. But some actively managed target funds charge 0.50% or even 0.75%.

That sounds small. It isn't. Over 30 years, a 0.5% difference in fees can eat up six figures of your retirement nest egg. It’s basically paying for a Mercedes you never get to drive. Always check if the fund is "passive" (indexing) or "active." Usually, the passive ones are much better for the average person because they don't try to outsmart the market; they just track it.

Are Target Funds Good for Your Specific Risk Tolerance?

Most people are "risk-averse" until the market goes up 20%. Then they want more stocks. Then the market drops, and they realize they can't sleep at night.

Target-date funds solve the "behavioral gap." This is the gap between what a fund earns and what the investor actually keeps. People love to buy high and sell low because of panic. A TDF prevents this because you don't see the individual stocks dropping. You just see one line on your statement. It’s boring. And in investing, boring is almost always better.

However, these funds are "one size fits all." They don't know if you have a massive pension. They don't know if you're going to inherit a million dollars from your aunt. They don't know if you have a side hustle.

If you have a pension, you can actually afford to be way more aggressive with your 401(k). In that case, are target funds good? Maybe not. You might be better off picking a fund dated 10 years later than your actual retirement date just to keep more stocks in the mix.

The Customization Problem

The biggest knock against TDFs is the lack of control. You can't tilt toward small-cap stocks. You can't decide to avoid international stocks if you think Europe's economy is a dumpster fire. You get what they give you.

Real-world example: In 2022, both stocks and bonds crashed at the same time. Usually, bonds go up when stocks go down. Not that year. People in target-date funds who were close to retirement saw double-digit losses. They thought they were "safe" because they had a lot of bonds, but the bonds failed them. This is a rare event, but it proves that "set it and forget it" doesn't mean "zero risk."

Comparing the Big Three: Vanguard vs. Fidelity vs. Schwab

If you're looking at these, you're likely choosing between the titans.

Vanguard is the gold standard for many because their TDFs are built with low-cost index funds. They tend to have a higher international exposure than some people like—roughly 30% to 40% of the equity side.

Fidelity is interesting because they offer two versions. They have the "Fidelity Freedom Index" funds (the cheap ones) and the "Fidelity Freedom" funds (the expensive, actively managed ones). If you're in a 401(k), check which one your employer picked. If it’s the active one, you’re likely paying way too much for "expert" managers who often underperform the index anyway.

Schwab usually wins on price. Their target-date index funds are incredibly cheap. They use a "through" glide path, which means they stay a bit more aggressive for longer.

- Vanguard: Balanced, heavy international, very cheap.

- Fidelity Index: Simple, reliable, low cost.

- Schwab Index: Often the lowest fee, slightly more aggressive.

Tax Inefficiency in Brokerage Accounts

Here is a warning most people miss: don't put target-date funds in a regular, taxable brokerage account. They are designed for IRAs and 401(k)s.

Why? Because the fund managers have to rebalance the internal holdings to keep the glide path on track. When they sell stocks to buy bonds, it creates capital gains. In a 401(k), you don't pay taxes on those gains. In a regular brokerage account, the IRS will send you a bill every year even if you didn't sell a single share of the TDF itself.

Vanguard actually got sued over this a few years ago. They changed some internal rules that caused a massive "capital gains distribution" for people holding these in taxable accounts. Some people ended up with tax bills in the tens of thousands of dollars for money they hadn't even spent. Keep TDFs in your retirement buckets only.

The Strategy for "Early" Retirees

If you plan to retire at 45 or 50, the math for target-date funds breaks. The fund assumes you’ll be 65. If you use a 2045 fund but you retire in 2030, the fund will be way too heavy in stocks when you start taking withdrawals. This creates "sequence of returns risk." If the market crashes right when you retire at 45, your 90% stock portfolio in that TDF will get crushed, and you won't have time for it to recover.

👉 See also: How Much Does Costco Manager Make: What Most People Get Wrong

For FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) followers, TDFs are usually a bad fit. You need a custom bond ladder or a much more nuanced approach to cash flow.

Is There a Better Way?

The alternative is the "Three-Fund Portfolio."

- A Total Stock Market Index Fund

- An International Stock Index Fund

- A Total Bond Market Index Fund

You buy these yourself. You set the percentages. You rebalance it once a year on your birthday. It’s slightly cheaper than a target-date fund and gives you total control. But be honest with yourself—will you actually do it? Or will you forget for three years and realize your portfolio is 95% Tesla and 5% hope?

For 90% of people, the convenience of the target fund outweighs the 0.05% you save by doing it yourself.

Actionable Steps for Your Portfolio

If you're currently holding a target-date fund or thinking about it, don't just click "buy." Do this first:

1. Check the "Index" tag. Ensure the word "Index" is in the fund name. If it’s not, you’re likely paying for active management that isn't worth the premium.

2. Look at the Glide Path. Go to the provider's website (Vanguard, BlackRock, etc.) and look for the chart showing the stock/bond split over time. If you want to be more aggressive, pick a fund dated 5-10 years after your actual retirement date.

3. Verify the Account Type. Only hold these in tax-advantaged accounts like a 401(k), 403(b), or Roth IRA. If you have one in a standard Vanguard or Fidelity brokerage account, consider moving it to a more tax-efficient Total Stock Market fund instead.

4. Evaluate Your Total Picture. If you have a house that's paid off and a solid pension, you can treat those as your "bonds." This means you can afford to stay in a "Target Date 2065" fund even if you’re retiring in 2040, keeping your growth potential high.

5. Avoid Performance Chasing. Don't swap from a 2040 fund to a 2050 fund just because the 2050 fund did better last year. It only did better because it had more stocks. If the market turns, it will do worse. Stick to the timeline that matches your need for cash.

Ultimately, target funds are excellent tools for building wealth without the stress of day-trading. They protect you from your own worst impulses. Just make sure you aren't paying a "convenience tax" in the form of high expense ratios, and keep them out of your taxable accounts to avoid a headache come April.